The famous mountain doctor from Emmental

Through his sometimes unconventional methods, Michael Schüppach made a name for himself as a barber-surgeon well beyond the Emmental region.

The role of the barber-surgeon

From as early as the Middle Ages, barber-surgeons were medically trained to treat wounds and diseases, as well as shaving, hair cutting and personal grooming. The services of barber-surgeons were so in demand that they were often called on to treat soldiers during wartime. However, the quality of training varied according to the knowledge of teachers and the talent and ambition of students.

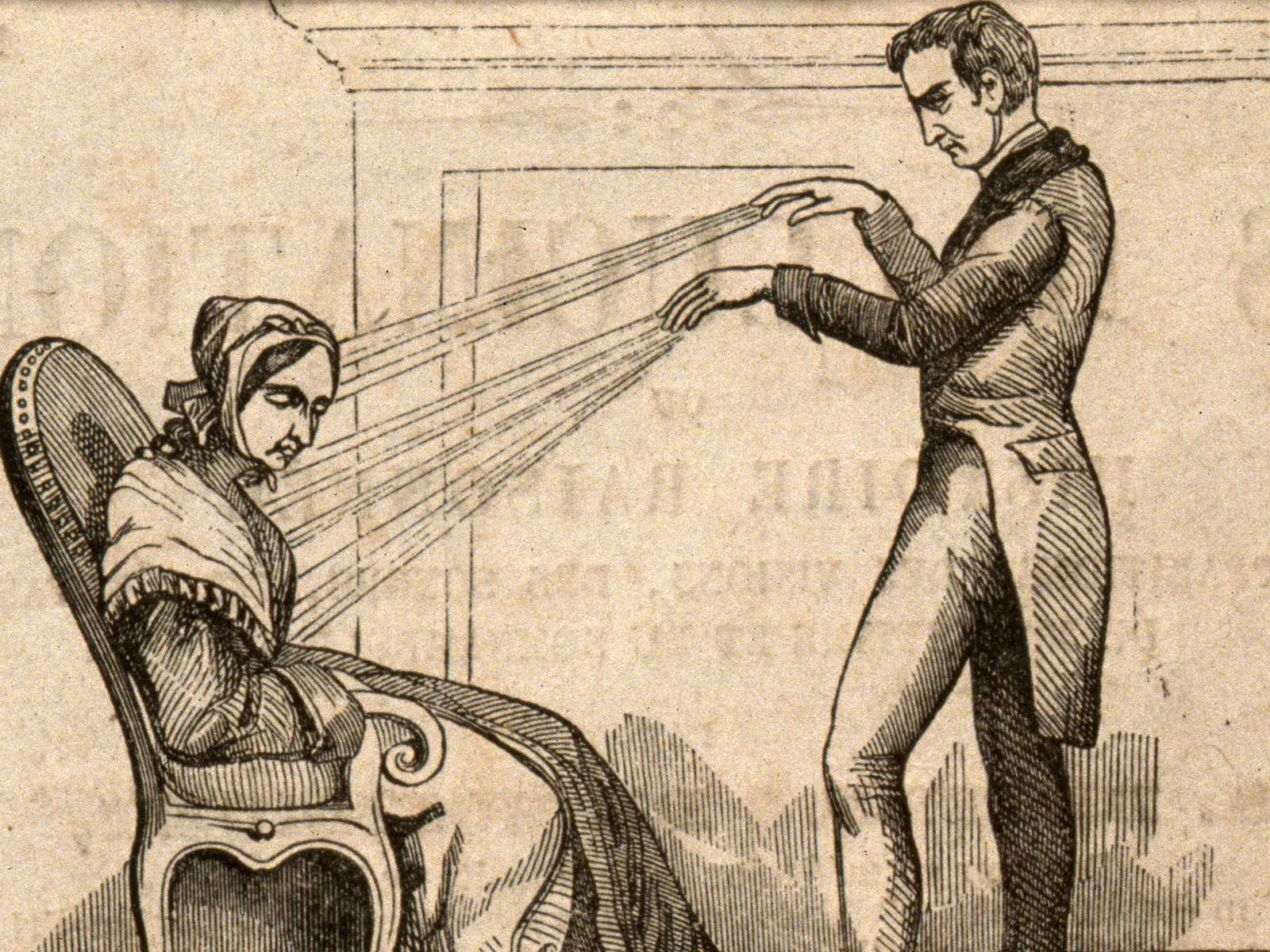

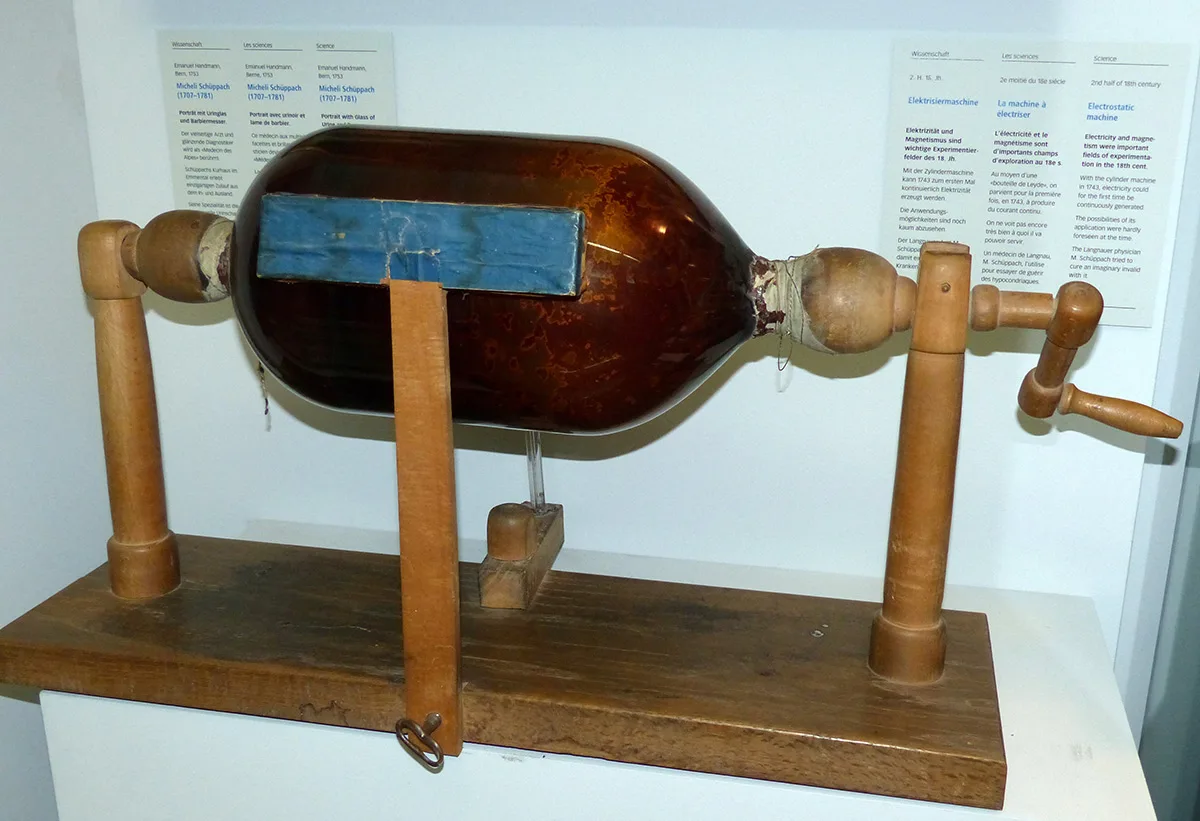

Between chemistry and natural healing

Schüppach was a lifelong learner and knew as much about natural healing as he did about chemistry. He usually mixed his own tinctures and healing potions and sometimes gave them curious names such as ‘Blüemliherz’ (little flower heart), ‘Freudenöl’ (pleasure oil) and ‘liebreicher Himmelstau’ (loving sundew). Schüppach also kept a diary about his patients, documenting their ailments, treatments, and the prescribed medicines with painstaking precision.

A trailblazer for tourism

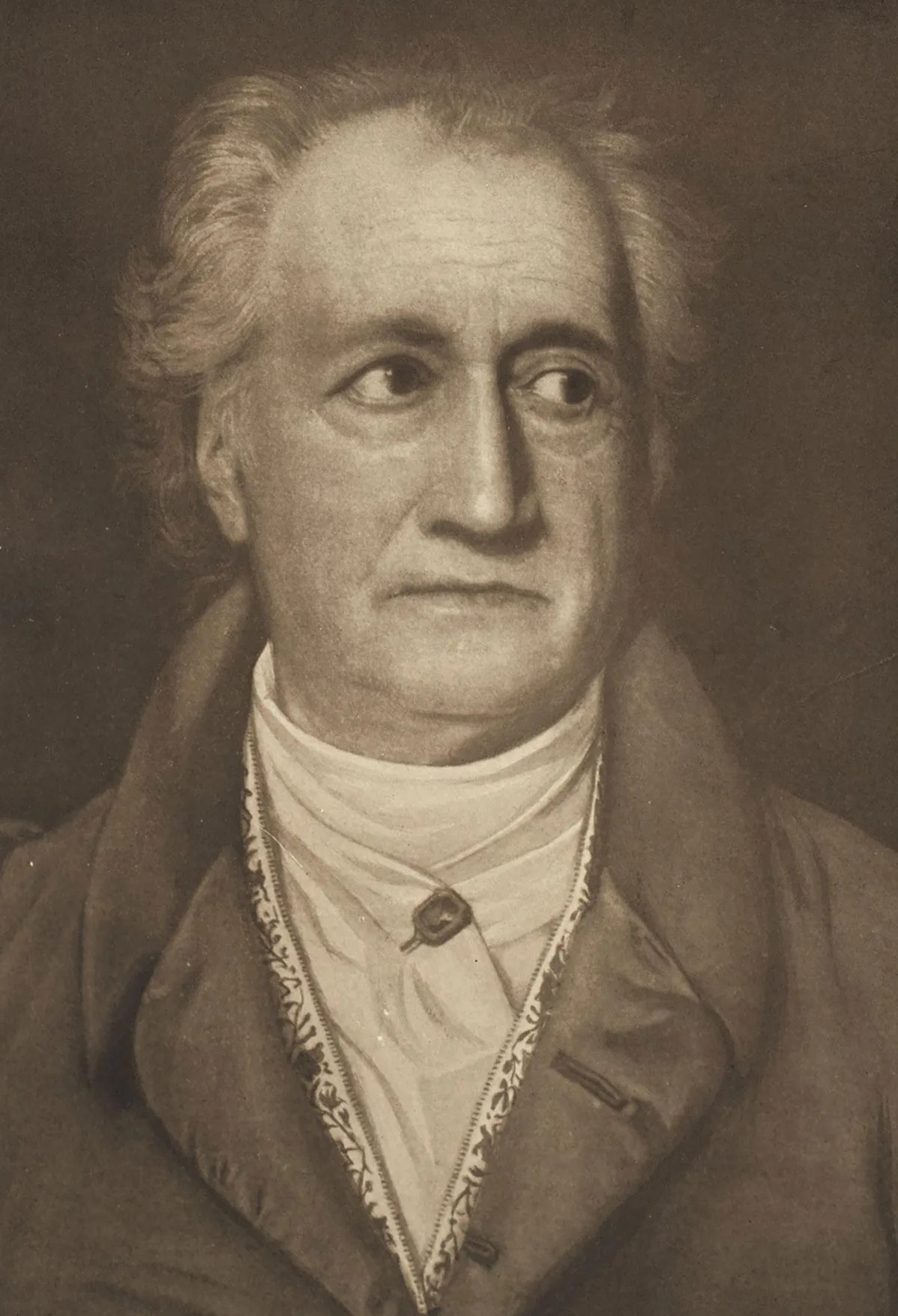

But not everyone admired the mountain doctor from Emmental. One of his harshest critics was Albrecht von Haller (1708–77), a famous physician and natural scientist from Bern. Without ever visiting Schüppach, von Haller dubbed the Langnau doctor as a “market trader”, basing his views mainly on reports by Jakob Köchlin. Köchlin, also a doctor, was from Alsace and had visited Schüppach “the farmer from Langnau” in 1775.

But all this criticism didn’t harm the mountain doctor’s popularity in the slightest. At peak times he would see between 80 and 90 patients in his small practice. His guests would often stay overnight or for several days. In 1733 Schüppach acquired the Gasthof Bären Inn in Langnau, to practise there and also to be able to offer accommodation. In 1739 a spa building was added to the house and laboratory. Schüppach therefore built his own little empire and, in doing so, launched tourism in the region.

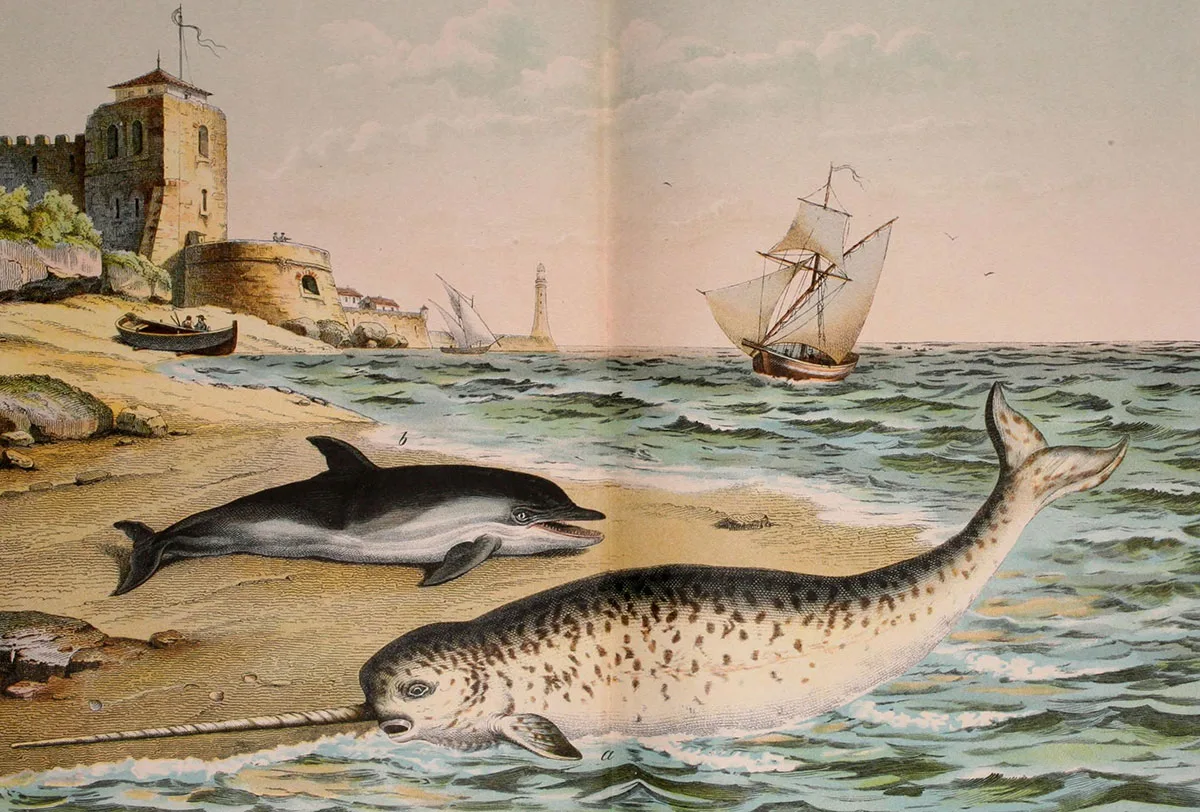

Despite his numerous medical successes, Schüppach was a child of his time and – like most of his local patients – he was highly superstitious. His practice in Langnau contained many a superstitious remedy, such as pulverised gemstones, spiders, toads and even the horn of a ‘unicorn’ (narwhal tusk).

Schüppach had to be admonished twice before he finally obtained his master’s certificate from the Bernische Chirurgische Societät in 1746 and from then on was able to use the title ‘Medicinae et Chirurgiae Practico’.

Yet Schüppach seemed not to pay much heed to his own medical advice. Contemporary pictures and descriptions suggest that he was a corpulent and ponderous man who was usually sedentary when he saw patients. At the age of 74 he suffered a fatal stroke and was subsequently forgotten for many years.