From Vesuvius to Moscow – without leaving Switzerland

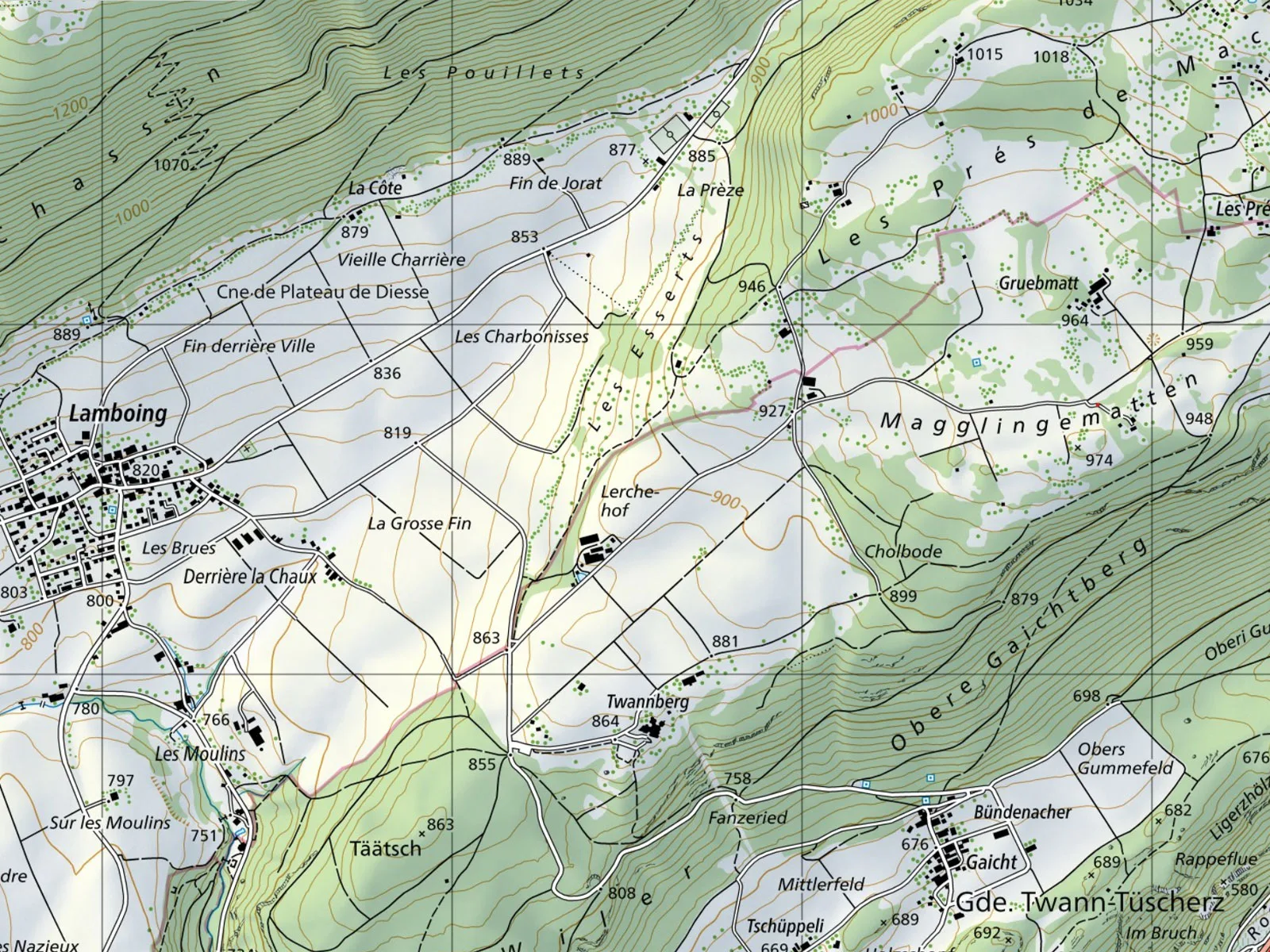

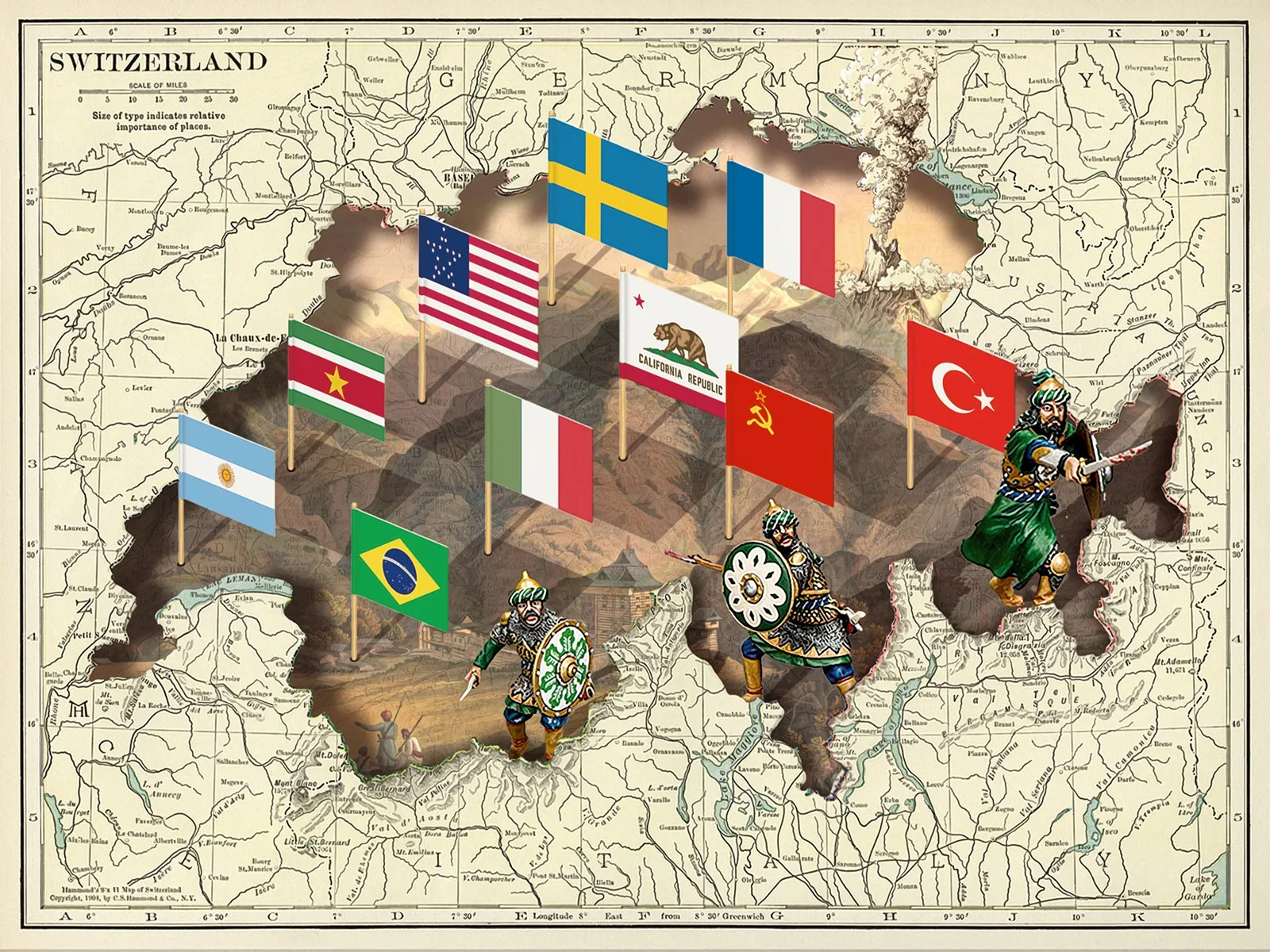

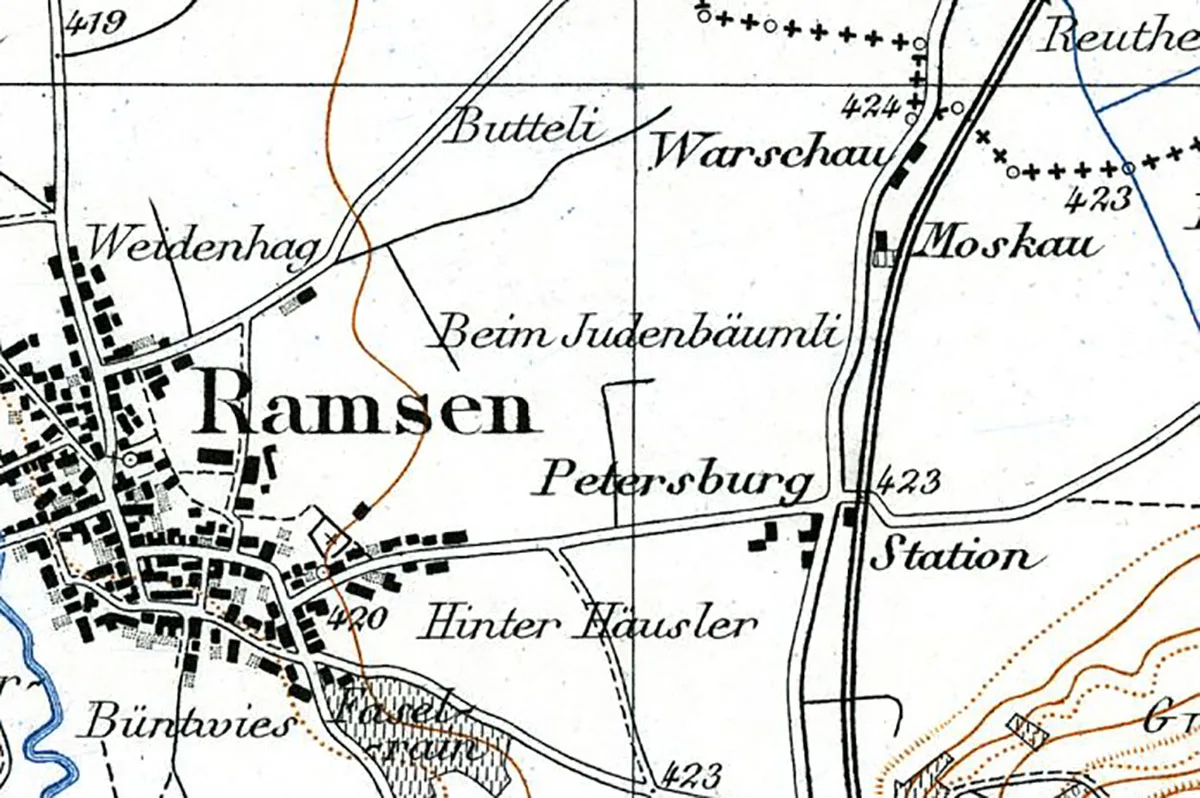

Sibirie, Afrika, Le Brésil, Himalaia – as toponyms go, none of these place names sounds particularly Swiss. And yet they are all to be found right here in Switzerland, where an estimated several hundred such ‘exotic’ names have been borrowed from elsewhere.

Humorous names

Far, far away

Emigrants…

…and homecomers

Foreign armies

World history reflected in Switzerland

The Holy Land

The eternal Saracens