Conserved values

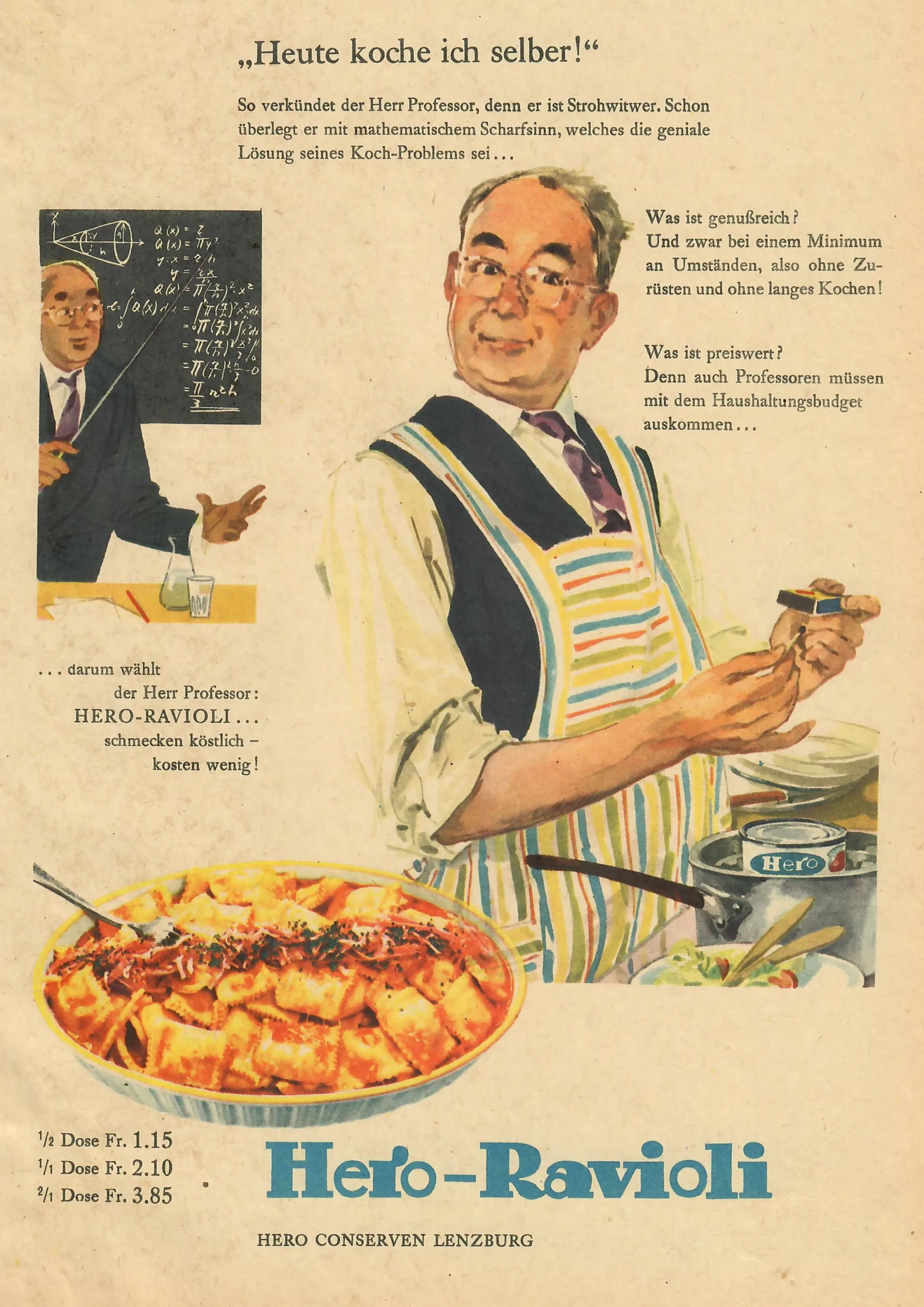

The lowly tin can became a household staple in the emerging consumer society of the 1950s. And the way tinned foods were advertised gives us an insight into social and cultural change.

Preserved fruit and values

Still, the behavioural researchers see this shift in consumption as being driven by ‘bad conscience’ on the part of housewives, who deep down feel duty bound to prepare homemade meals rather than simply putting convenience foods on the table.

The Italian holiday straight from a tin