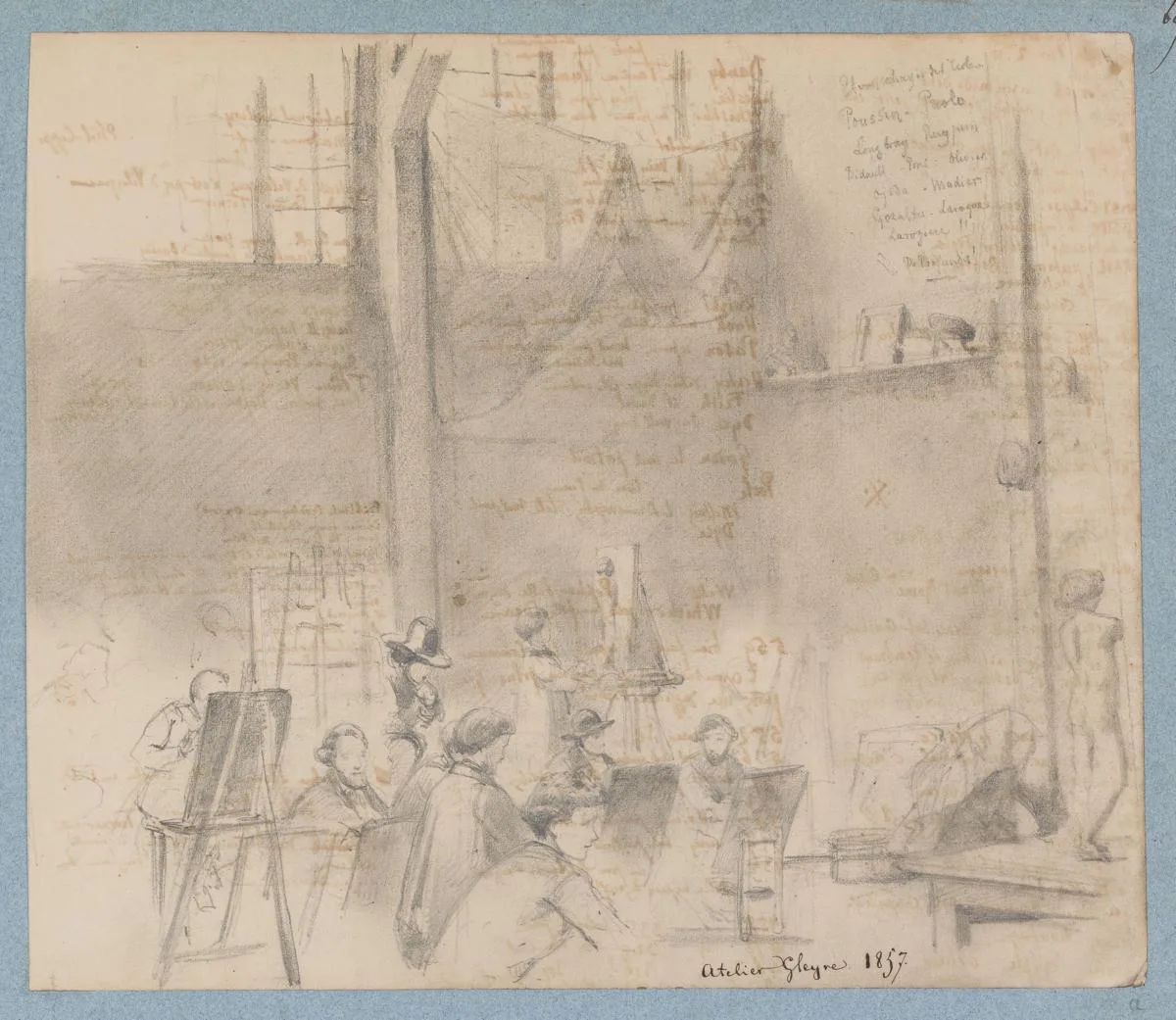

The Swiss teacher of the Impressionists

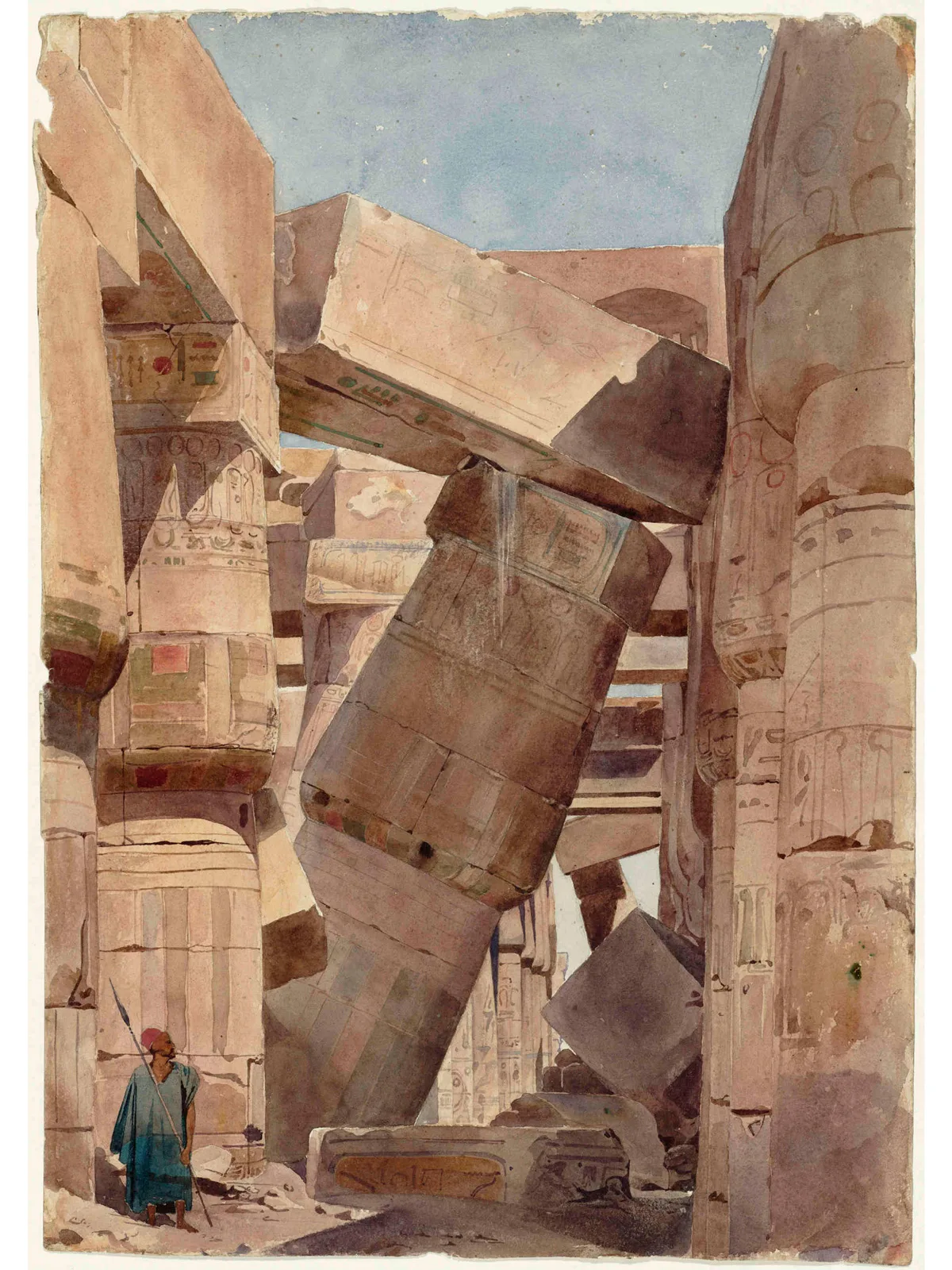

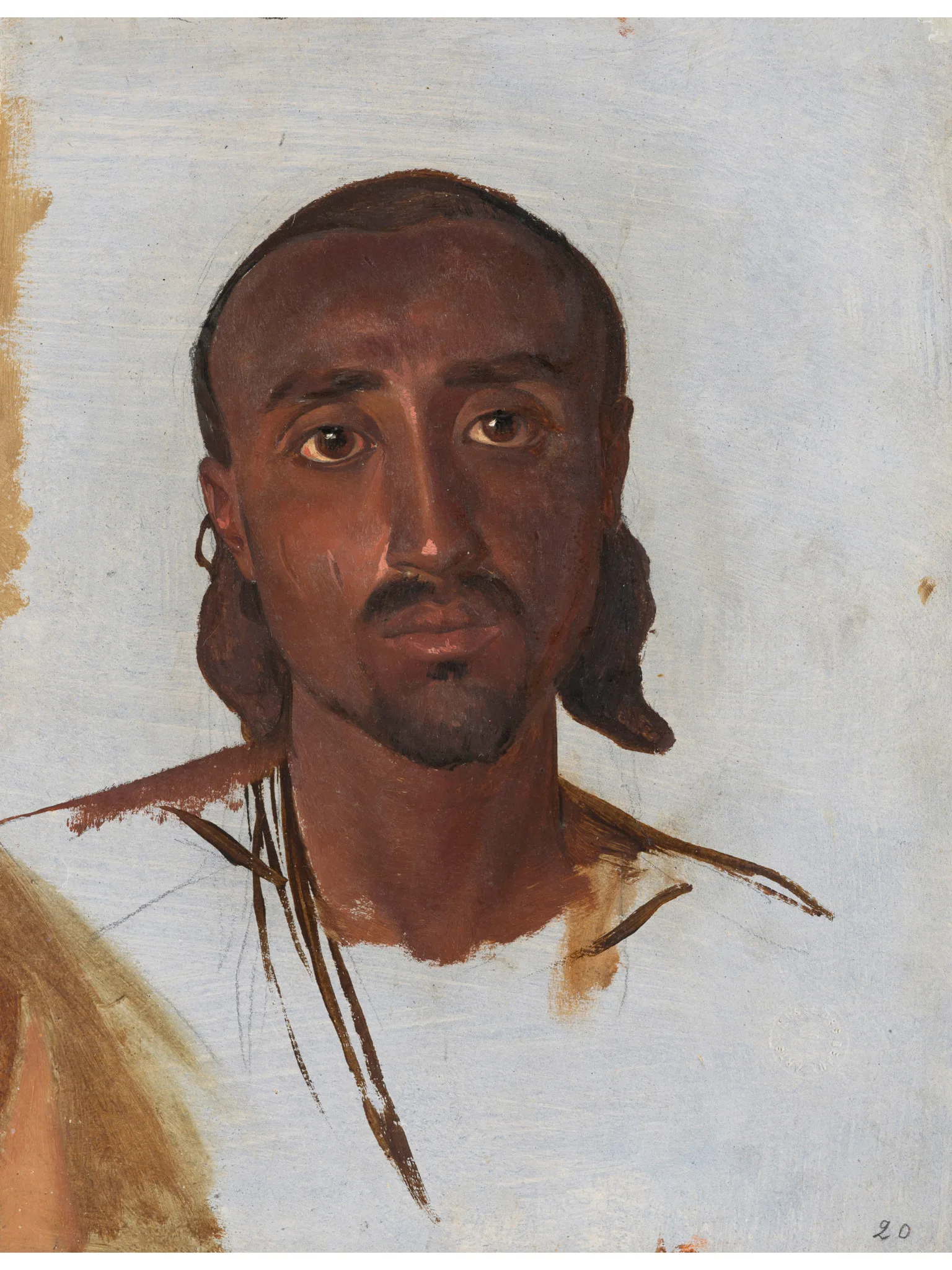

Swiss painter Charles Gleyre (1806-1874), from Chevilly in the canton of Vaud, was an illustrious figure in the 19th century. Painters such as Albert Anker und Auguste Renoir studied at his Paris studio. Gleyre’s own works fused influences from Romanticism and Impressionism.