Vandalism as a political tool in the Helvetic period

The French invasion 225 years ago not only brought about major political upheaval in Switzerland, but also death and destruction. Vestiges of acts of vandalism to cultural property can still be seen today.

Napoleon and the conquest of the Old Swiss Confederacy

Where does vandalism come into it?

The days of terror in Nidwalden in September 1798

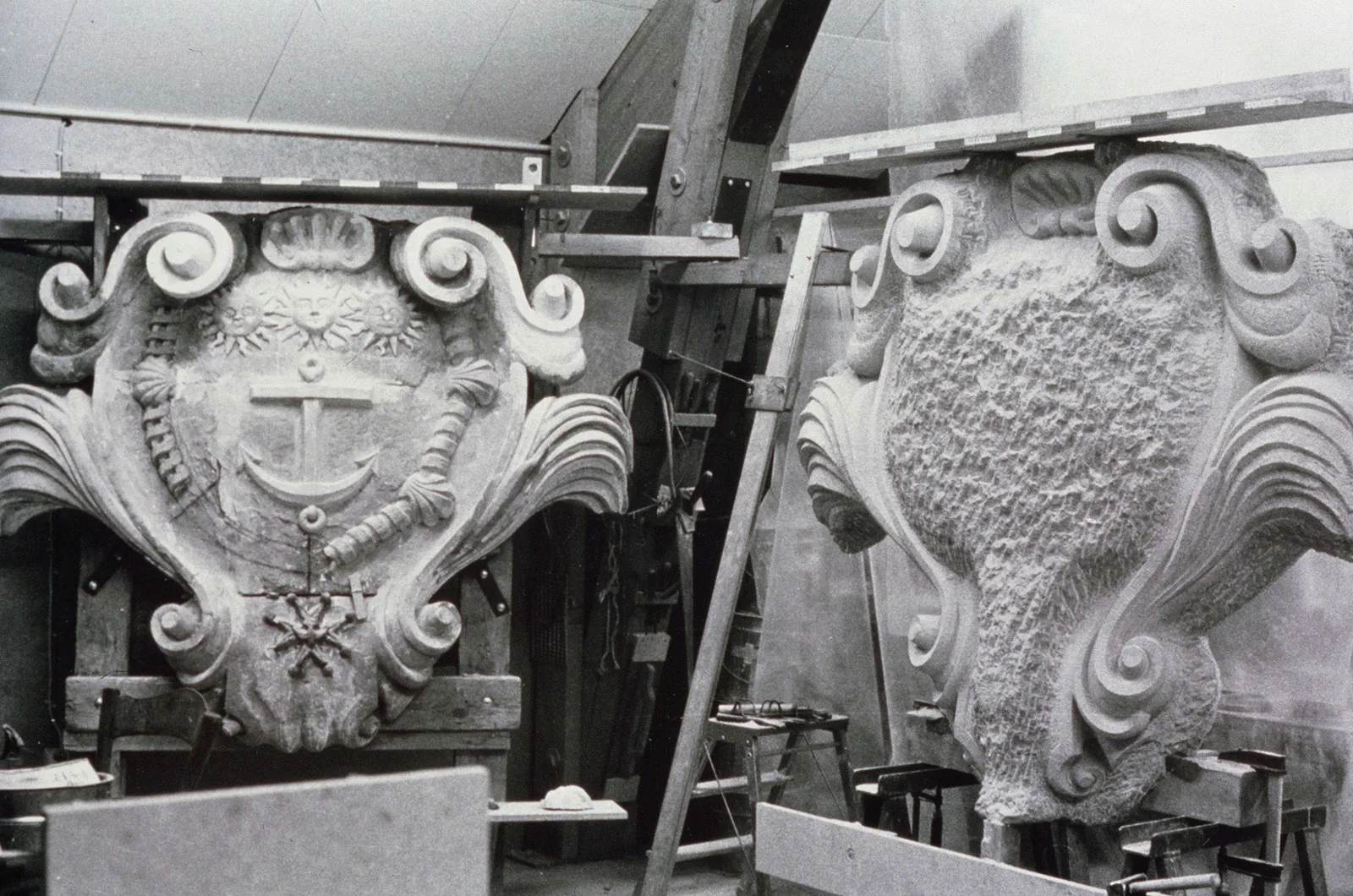

Fury against historical coats of arms

Vandalism of Solothurn Jesuit Church

Eradication of an historical event?

ZAK – the academic journal of the Swiss National Museum

This is a summary of an article in the Journal of Swiss Archaeology and Art History (ZAK), which the Swiss National Museum has been publishing for exactly 80 years. ZAK is published four times a year and can be subscribed to. Further information available at: landesmuseum.ch/zak