Martin Bodmer: building a library of world literature

Swiss intellectual and bibliophile Martin Bodmer dedicated his life to preserving written knowledge. His extensive collection is now part of the UNESCO Memory of the World.

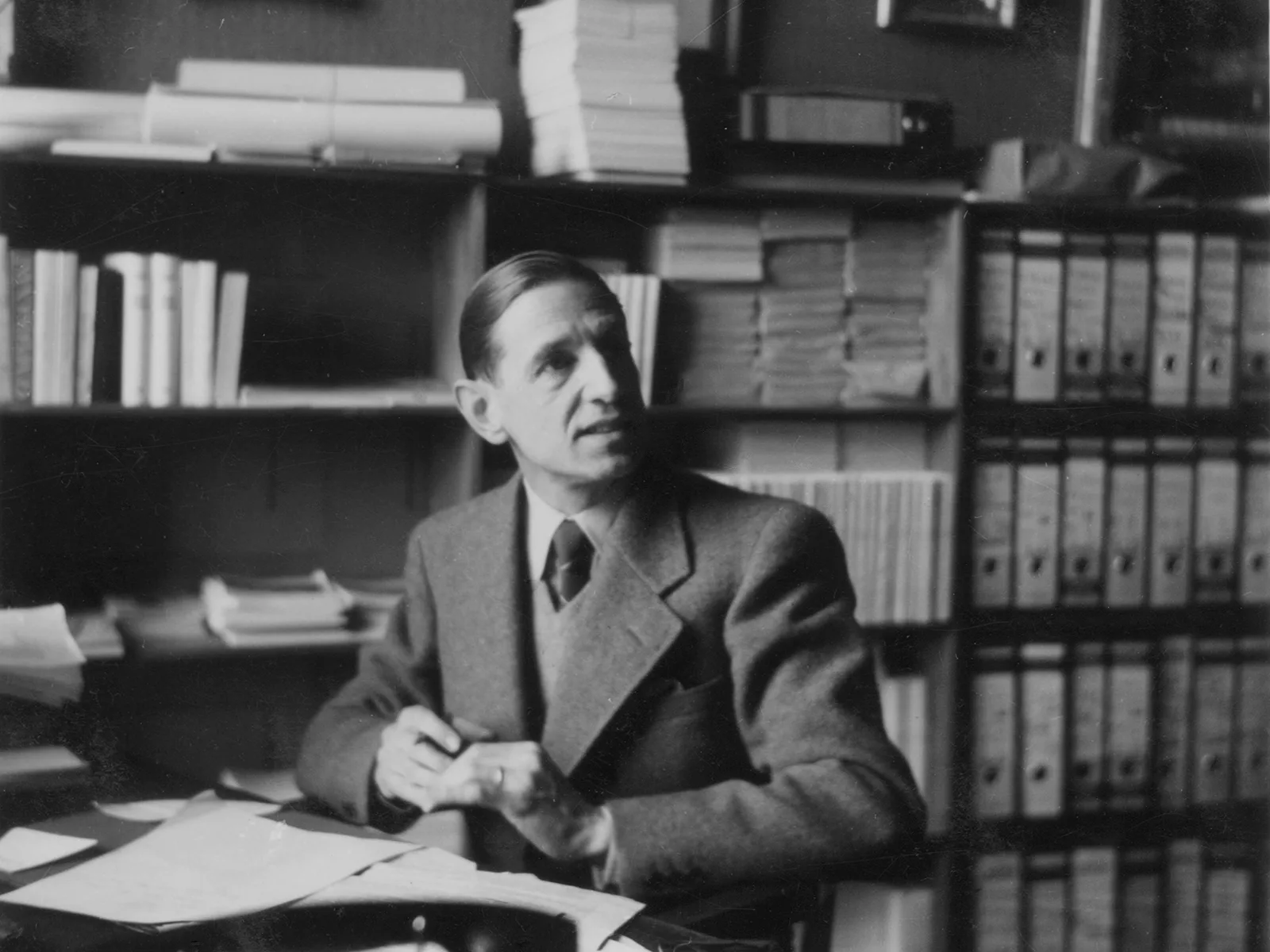

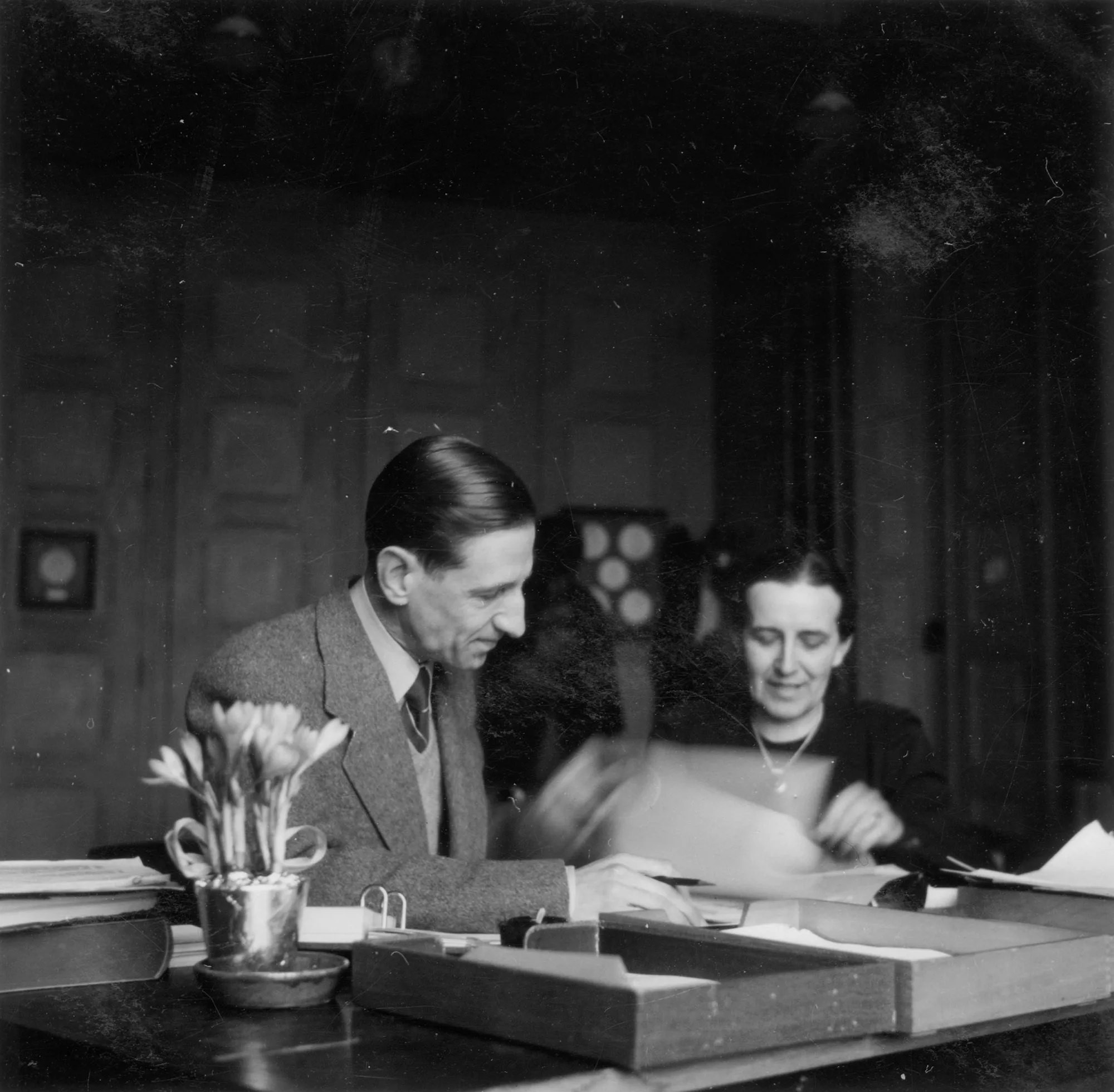

Fast forward many decades to Cologny in the canton of Geneva, where, in the hushed ambience of an office, a library assistant types the words and thoughts of a sharp-featured man. For almost ten years, Martin Bodmer regularly recorded his intellectual legacy in manuscript fragments, which he referred to as “Chorus mysticus”, a Latin expression in honour of Goethe. Bodmer’s text, as fascinating as it was fragmented, remained incomplete, was never published and was quickly forgotten about.

His collection, however, endured with over 150,000 documents from 80 cultures spread over three millennia. Three weeks before his death, Martin Bodmer signed the foundation deed to establish the Bibliotheca Bodmeriana, ensuring the continuation of his collection. This collection, which he referred to as his “geistiges Bauwerk” (intellectual construction), was more than just a library. It was closer to a museum dedicated to the evolution of the human mind, documented in written texts. Bodmer wanted to show “humankind’s journey of self-discovery” through his collection.

An all-consuming obsession

Bodmer quickly became a key figure in the intellectual circles of his time, notably when he founded the Gottfried-Keller Prize at the tender age of 22. The prize is for Swiss authors and it was the most generously endowed award in the German-speaking world at the time.

Bodmer later wanted to create a place where the history and culture of humanity would be accessible to everyone. The venue was to benefit posterity and serve as a source of inspiration – in keeping with the concept of “world literature”. This concept was elaborated by Goethe in the 19th century and is based on the transnational dissemination of key works.

[World literature] means the evolution and geographical distribution of the written record and, at the same time, is restricted to those linguistic works that transcend time and national borders. In other words, works defined by the power of the human content and the magic of the language.

Knowledge for all

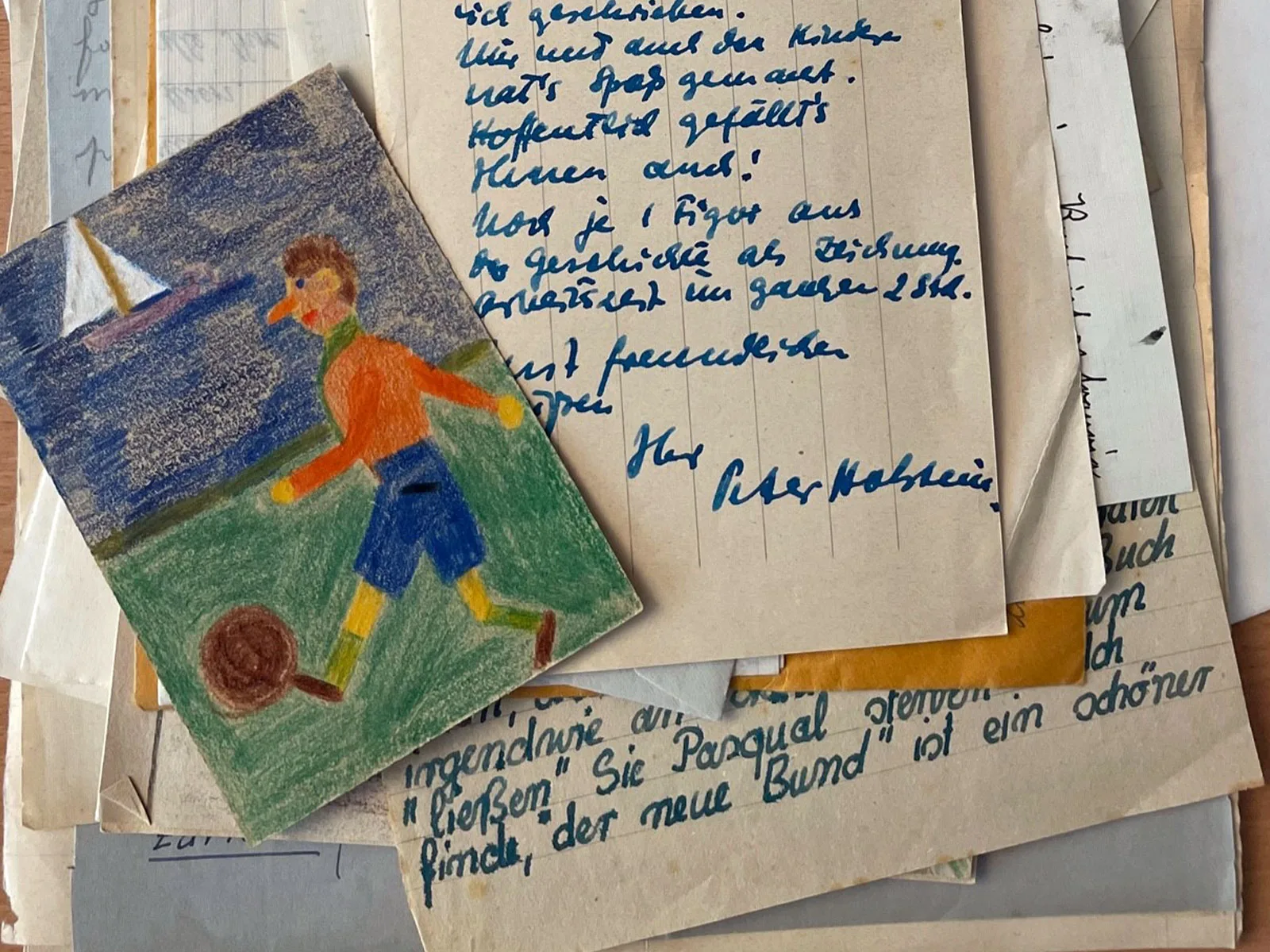

During the Second World War, Bodmer worked in the Intellectual Aid section of the International Committee of the Red Cross. This humanitarian programme provided books to prisoners of war to uphold their intellectual and moral dignity. 1.5 million books were gathered on his watch and distributed among the prisoners of the warring countries. He considered this an important source of comfort and education, something to overcome the horrors of war.

Provider of a public service, or in thrall to books?

Odile Bongard, Bodmer’s personal secretary for 30 years, described his character as that of a “solitary man who valued order and simplicity, but above all, quality”. Every day, he observed the same routines: time with his collections, making notes, before returning to the peace and quiet of his home.

The bibliophile’s legacy

Martin Bodmer died in Geneva in 1971. On his gravestone is written: “The things you have done are only seen after you die”.