Switzerland’s first female photographer

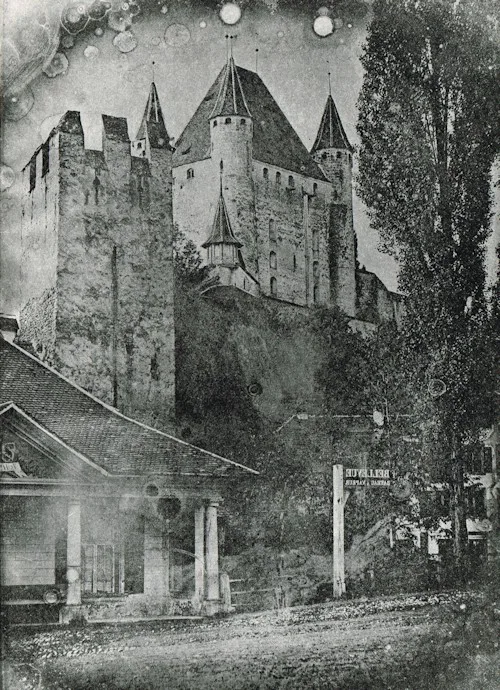

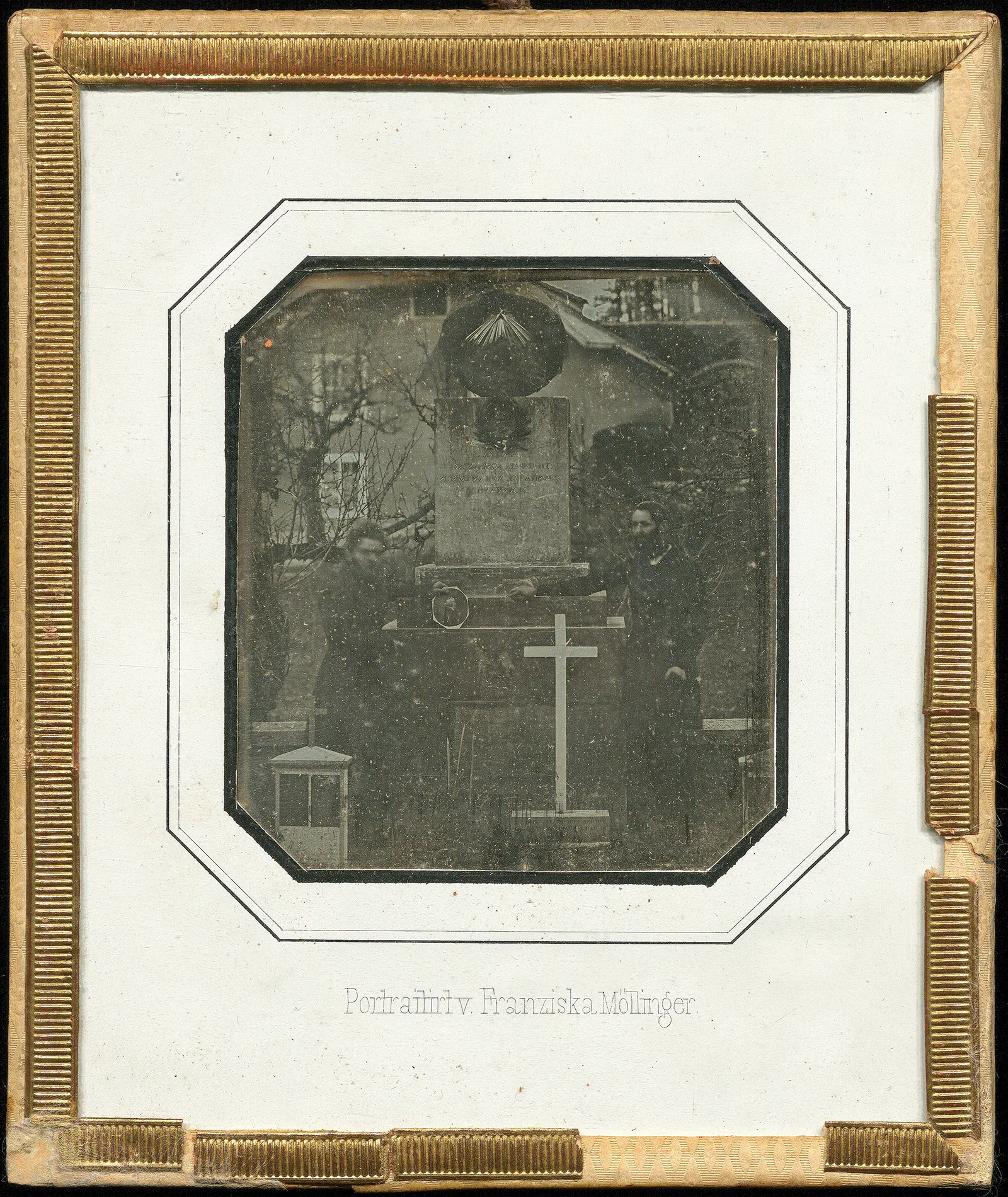

Franziska Möllinger was not only the first woman to work as a photographer in Switzerland, she was also a pioneer of the use of photographs as templates for prints. There are only two original photographs by Möllinger in circulation today, the second of which surfaced in 2024.

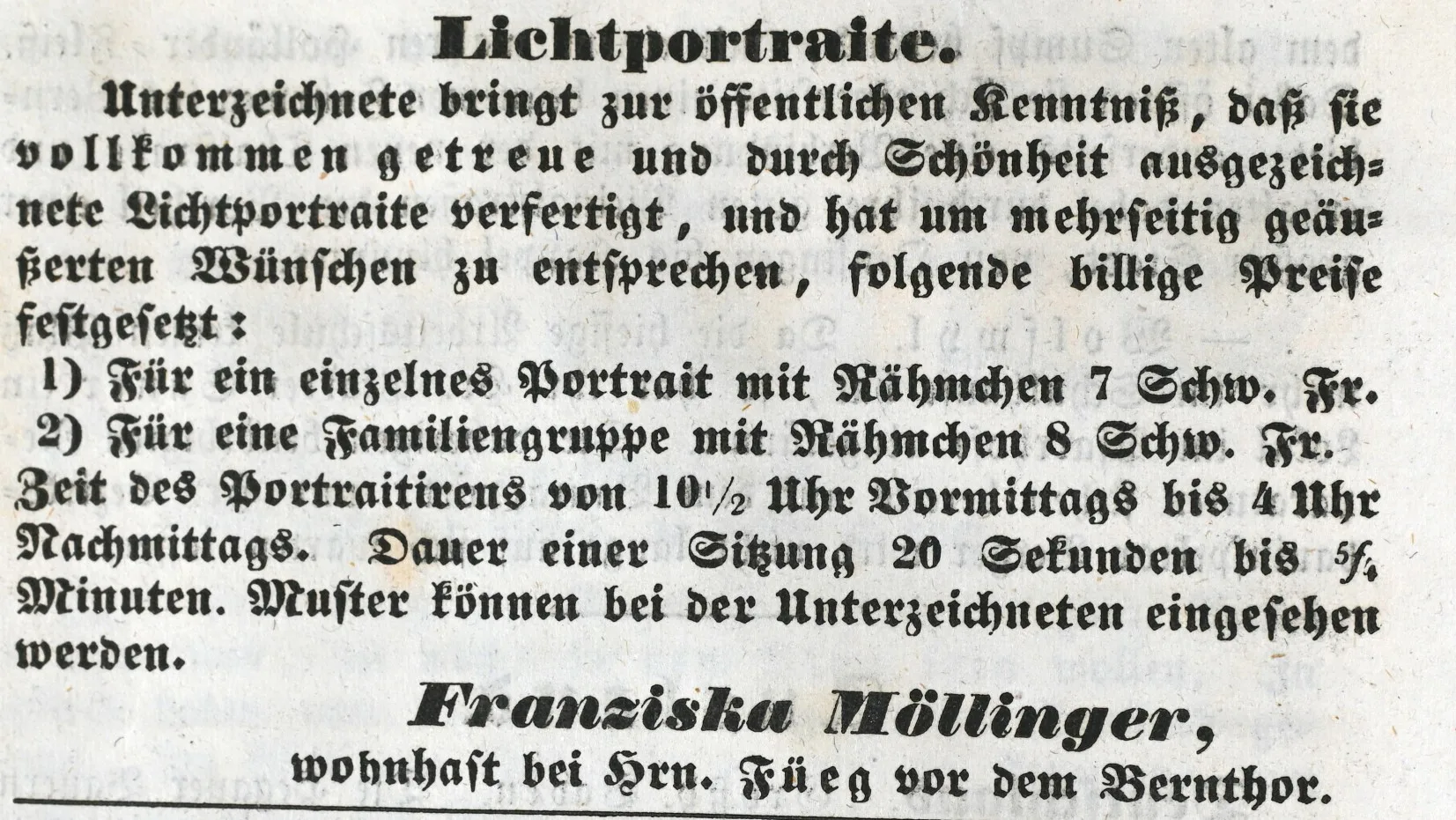

Standing out amongst all these offers, listings and information on 8 April 1843 is an advertisement – slightly larger than most of the others and highlighted in bold – with the heading ‘light portraits’. In it, a certain Franziska Möllinger announces “that she produces entirely faithful and charming light portraits”. According to the advert, an individual portrait is available for seven Swiss francs (around CHF 120 today), and a family group portrait for one franc more. The person behind this announcement was none other than Switzerland’s first female photographer – and one of the first worldwide.

Franziska Möllinger and the daguerrotype

And that is pretty much all we know about Franziska Möllinger as we only have a broad outline of her life story. Paradoxically, there are no surviving images of this pioneering photographer and portraitist, so we can’t even get an idea of what she looked like.