The 100-year history of the Centovalli Railway

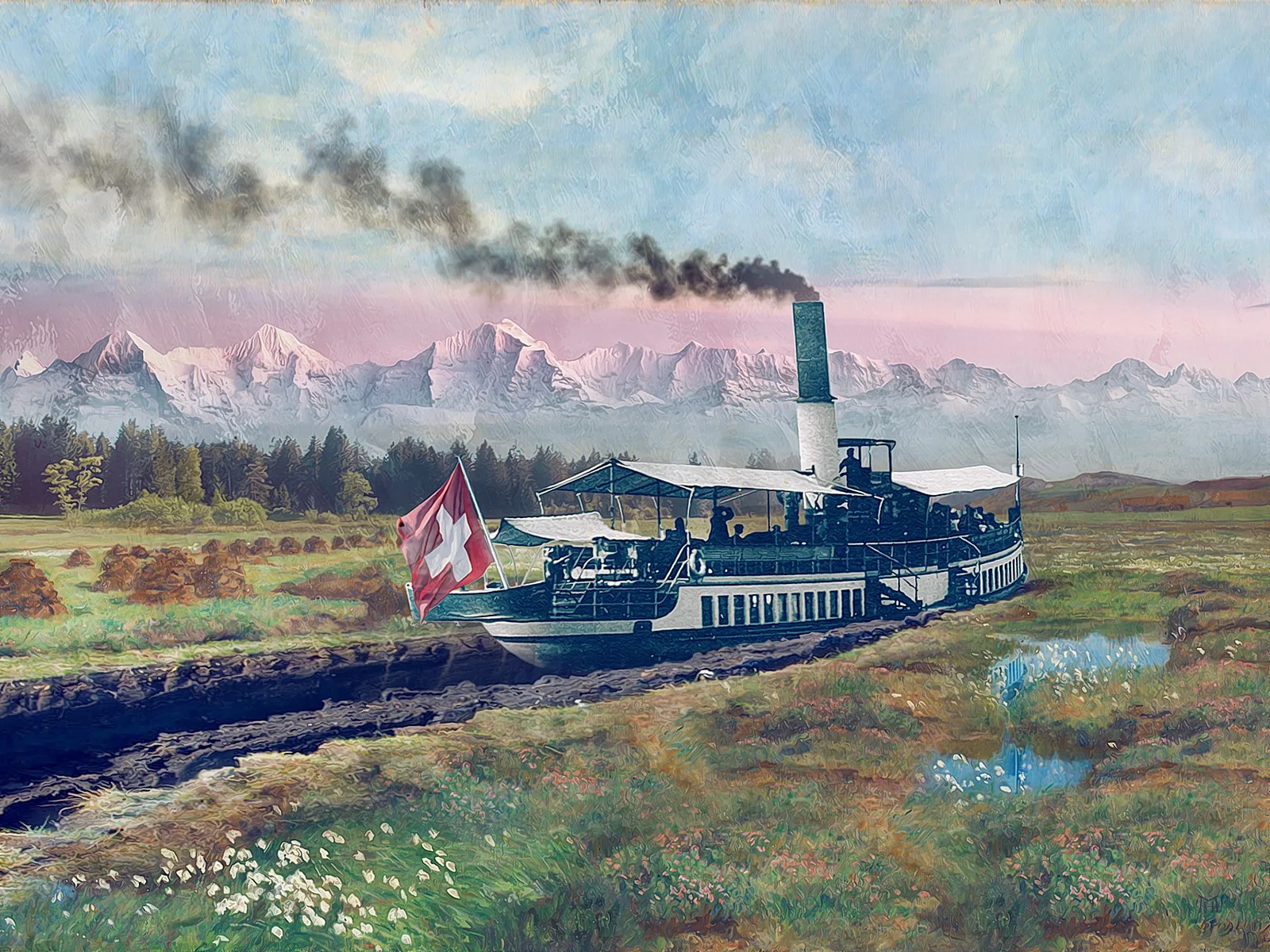

The Vigezzina-Centovalli Railway crosses 83 bridges and goes through 31 tunnels. It connects Switzerland to Italy and is the most direct route between the Gotthard and Simplon lines. The legendary narrow gauge railway in southern Switzerland celebrates its centenary in 2023/24.

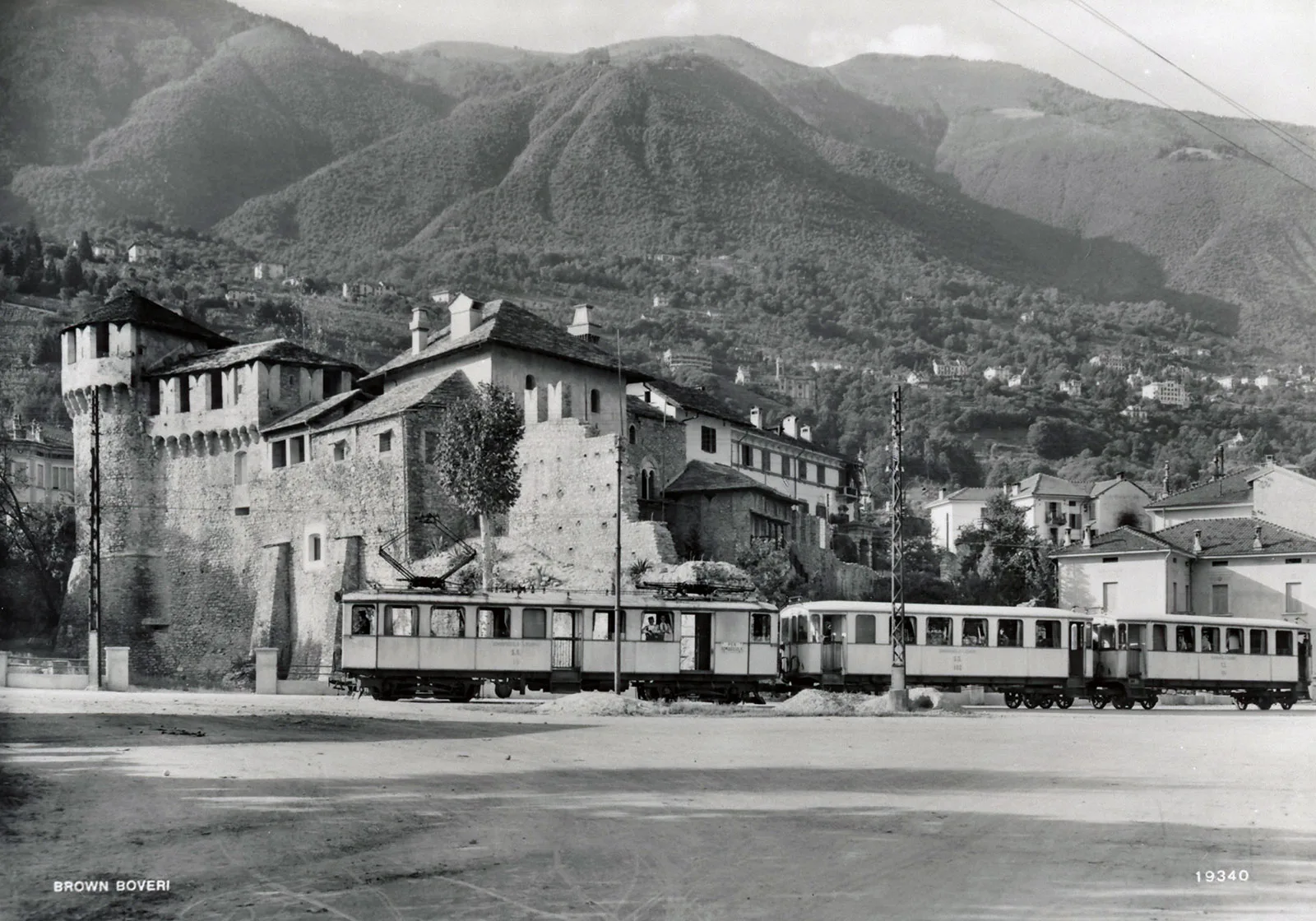

Locarno’s tramway and the Maggia Valley Railway

A beacon of hope in the Second World War

Infrastructure projects and the storm of the century

One of the world’s most beautiful railway lines

100 years of the Vigezzina-Centovalli Railway

The Swiss Museum of Transport is organising various activities and exhibitions to mark the centenary, such as a thematic display featuring a carriage from 1923.