Swiss National Museum

A one-track life

At the end of the 19th century, the world was gripped by ‘railway fever’. Swiss expertise was in high demand. Jakob Müller left Lucerne to move to present-day Turkey, where he eventually became the director of the legendary Orient Express.

When Jakob Müller left school, railway construction was booming in Switzerland. In 1875, he took up a stationmaster’s apprenticeship with Alfred Escher’s Nordostbahn rail company. These days, we’d say he got involved in a start-up. The railways were, so to speak, the 19th century version of the internet. They revolutionised the economy, shortened distances, enabled commerce and businesses to expand, and created new industries such as electrical engineering.

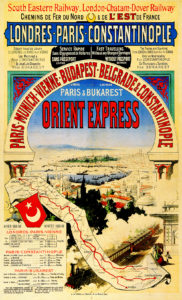

Since 1883, the legendary Orient Express has run daily between Paris and Constantinople (now Istanbul). Deutsche Bank, prompted by Emperor Wilhelm II, pulled the strings in the background. Alfred Escher’s other big start-up, the Schweizerische Kreditanstalt, was also involved. Together, these two institutions provided international financing for the Chemins de fer Orientaux train line. And there was already talk of pushing the railway on through Anatolia to Baghdad! No doubt about it, the industry had a future!

Orient-Express near Constantinople, postcard around 1900.

Wikimedia

After completing his apprenticeship Jakob Müller, born in 1857, moved to Constantinople with his colleague of the same age, Edouard Huguenin. Expert professionals from neutral Switzerland were in demand. The exciting, unfamiliar world and the fat pay packets were a big draw. Müller started at the very bottom as a booking clerk for the Chemins de fer Orientaux railway company. Huguenin went to the Asian side, working for the Anatolian railways. Step by step, the two rose to the top of their respective companies. In 1903, Jakob Müller was appointed deputy director, on an annual salary of 32,000 francs. Tax-free. That’s more than ten times what the Federal government was paying Patent Office clerk Albert Einstein at the same time. By now, Müller had married. His wife, Rosy, came from the wealthy Honegger silk merchant dynasty, from Rüti in the Canton of Zurich. They went on to have four children. When the family went to Switzerland on holiday, they travelled on the Orient Express, in a reserved Pullman carriage. Müller’s boss was Ulrich Gross, also known as ‘Turkish Ueli’, an urbane, sophisticated lawyer from Zurzach.

Portrait of the Müller family. The photograph was taken around 1910.

Jacques Edgar Müller, Zumikon

Portrait of Jakob Müller, taken around 1915.

Jacques Edgar Müller, Zumikon

THE ORIENT EXPRESS IN SWISS HANDS

At the start of the 20th century, the region fell on hard times. The weak Ottoman Empire became the plaything of the global powers. The Ottoman military had troops and material transported to the troubled Balkan provinces, but did not pay. Nevertheless, the railway company still turned a sizeable profit. As a ‘second pillar’, it operated the local railways in Constantinople and Thessaloniki. In 1912, the first Balkan War began. Gross took care of external relations, and Müller handled the day-to-day business, particularly the accounting. This became all the more important as the damage caused by the war increased. Sometimes railway stations were attacked, railway officials murdered and buildings set alight. And there were constant bomb attacks on the tracks. Müller noted down everything and forgot nothing. From 1911 to 1915, Gross and Müller sent more than 300 reports to the railway company’s headquarters in Vienna. Taking Müller’s records with him, in December 1912 Ulrich Gross travelled to the peace conference in London and successfully claimed compensation. In 1913, Gross resigned from his post as Managing Director of the Chemins de fer Orientaux. For the Board of Directors, it went without saying that Jakob Müller would replace him.

But the peace didn’t last long: in 1914, the First World War began. As late as 1915, Managing Director Müller was being remunerated with bonus payments which, in today’s monetary terms, were in the millions. He lost a portion of this money through war bonds. In November 1917, three days after his 60th birthday, he resigned. For hours, the Board of Directors sought to change his mind. But Jakob Müller knew that his position would become less important. In addition, he had cancer. He bought a villa on the Zurichberg and retreated to live out his life there. As unassumingly as he had carried out his work, Jakob Müller passed away quietly on 16 October 1922.

Advertising poster for the Orient Express, for the 1888-89 season.

Swiss Museum of Transport, Lucerne