Swiss National Museum/ASL

Lovely, lovelier, loveliest

One of the things that characterises a society is its prevailing ideal of beauty. A quick look at the past shows this is not a 21st century phenomenon.

Summertime is bathing time. When the weather gets warm, people head for the water. Whether swimming pool, river or lake, the leap into the cool water is part of a perfect weekend. But summertime isn’t just bathing time – it’s also a time of examining, comparing, and a time of abstaining, because in a bathing suit every lump and bump is on display. So one or other of your friends will prefer to stay at home and enjoy a cool-down in the bathtub. Anyone who goes in for self-examination starts to wonder, sooner or later, whether their body fits the current ideal of beauty. This worry is all-pervasive these days, and affects the sexes almost equally.

The ‘perfect’ man of the 21st century is tall, sporty and likes to show off his washboard abs in summer. But he’s not a bodybuilder, with bulging muscles that make an evening stroll along the waterside more of a lumbering plod. Athletic, yes – but in proportion, please! Today’s ‘perfect’ woman is tall, slim, toned and yet still feminine. Long hair is a must, and prominent cheekbones are highly desirable. If the woman has a natural look on top of all that, it might even qualify her for a career as a model.

Have we become slaves to outward appearance? Perhaps, but we’ve only got ourselves to blame, because beauty is whatever the majority of a society is able to agree on. And that also has a lot to do with what issues are important to that society.

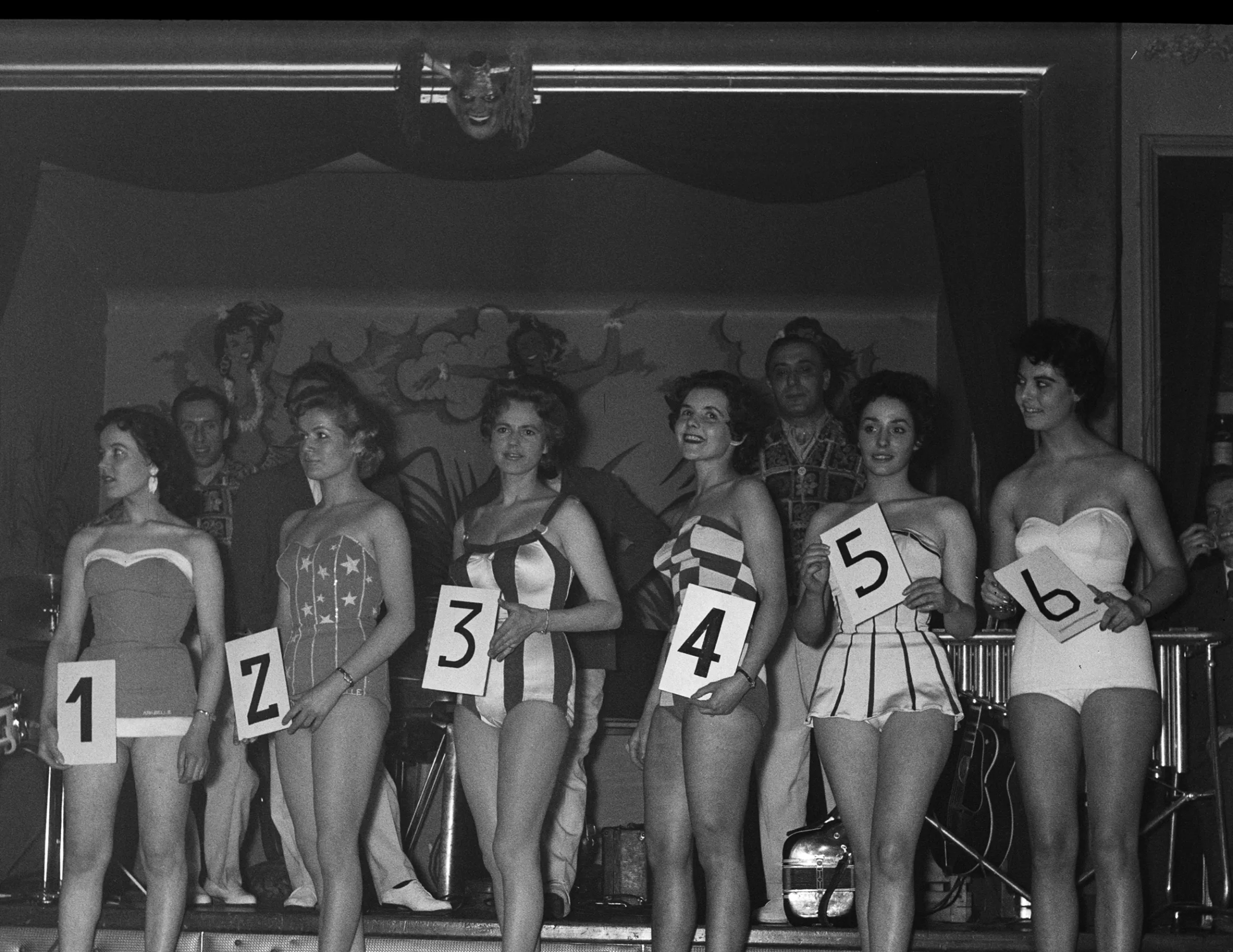

After the Second World War, long-haul travel to exotic, far-flung destinations and a tanned skin were considered stylish, and were evidence of a person’s growing prosperity.

Swiss National Museum

IDEALS OF BEAUTY CEMENT STATUS

A good example of this is the ideal of beauty in the post-war period. After the end of the Second World War and as the economic boom got under way, travelling to far-away countries was a must for a large section of society. Having a tan was in, even just to show everyone who’d stayed at home that you’d been away somewhere exotic. A summery suntan cemented your status. This ideal of beauty was taken to such an extreme that from the 1970s even the Barbie doll sported summery tanned skin. In the 17th and 18th centuries, by contrast, a porcelain complexion was the last word in sophistication. If this was not possible naturally, make-up was used to achieve the look. This was not without risks, because the white lead paste often used was toxic. Many people were aware of this, but continued to apply it anyway.

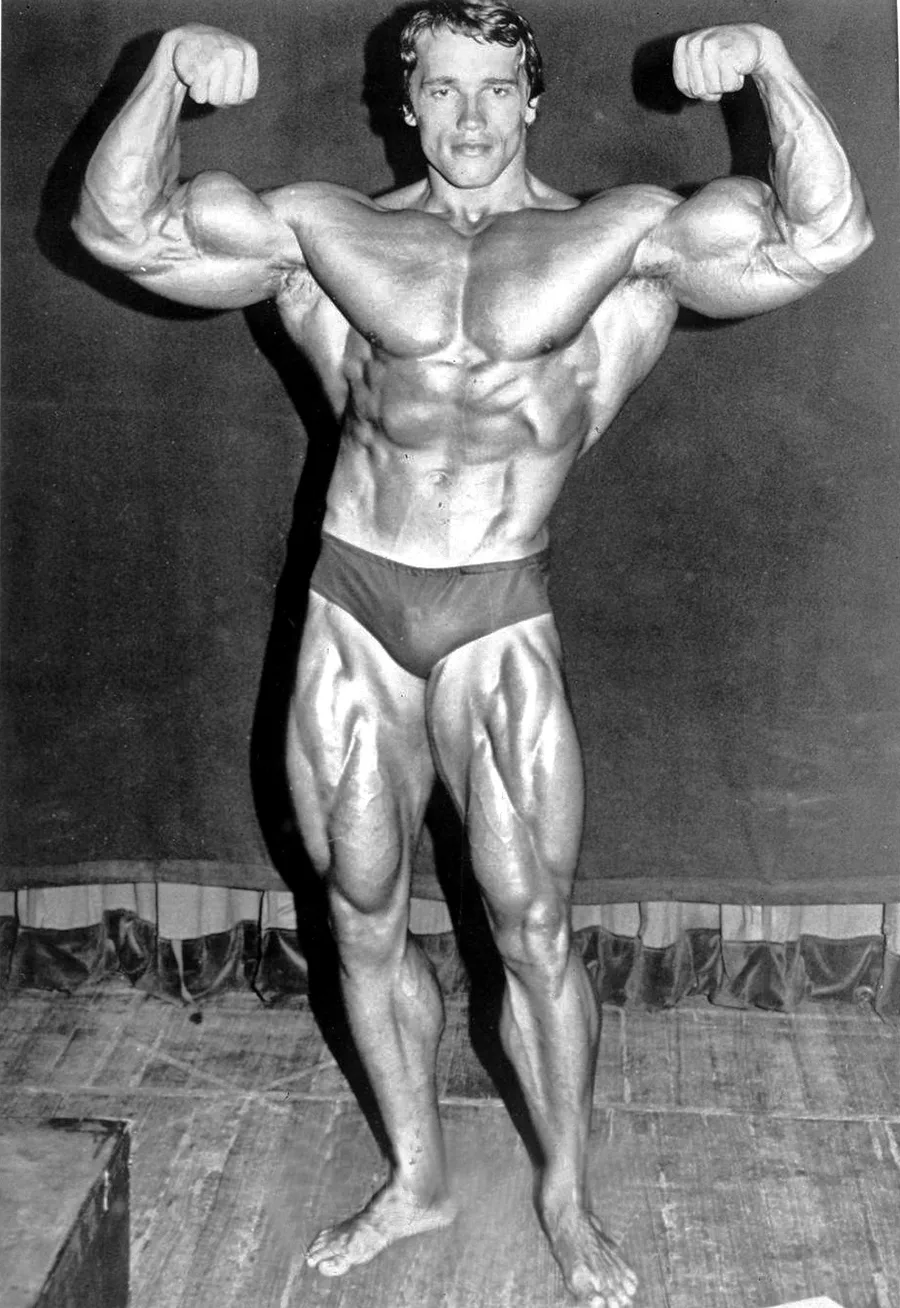

So the prevailing ideal of beauty is always a status symbol as well. We can see this clearly if we take a closer look at the evolution of the male body. In the baroque period, an ample body was considered attractive. Appearance reflected the lifestyle of that age: sensual pleasures, ostentation and decadence. In the late 19th century, a plump male body was the ideal. It was evidence of prosperity at a time when many were starving. At the beginning of the 20th century, the paradigm shifted towards the slimmer man. The better availability of nutritious food and the burgeoning film industry contributed to this. In the 1960s, young people started rebelling. This was reflected not only in their behaviour, but also in their outward appearance. Young men let their hair grow and paid less attention to their bodies. Physical fitness was frowned upon. After a muscular phase in the 1980s, which turned bodybuilding into a trend, the ideal of masculine beauty now seems to be back where it was at the beginning of last century.

Probably the most famous bodybuilder was Arnold Schwarzenegger, seen here in a 1974 photograph.

Wikimedia

AVERAGE IS BEAUTIFUL

When it comes to women, developments have taken a similar course. For centuries, women’s bodies with feminine curves were considered attractive and desirable. They symbolised fruitfulness and showed that one could afford to eat well, and thus enjoyed a certain degree of prosperity. In turn, therefore, the idea of status came into play. Over several decades, however, the picture has changed completely. In Western countries, a slim, toned female body is now considered the ideal. In other words, if you’re taking care of yourself you will not be overweight, even with today’s easy availability of food. Outward appearance as an indication of a person’s character.

After all, beauty is what the majority of a society is able to agree on, and usually that is not the extreme, but an average value. Or, to put it another way, the beauty ideal is always the best compromise on which a given group of people can agree. Needless to say, cultural differences also play a major role.