A marvellous fairy named Electricity

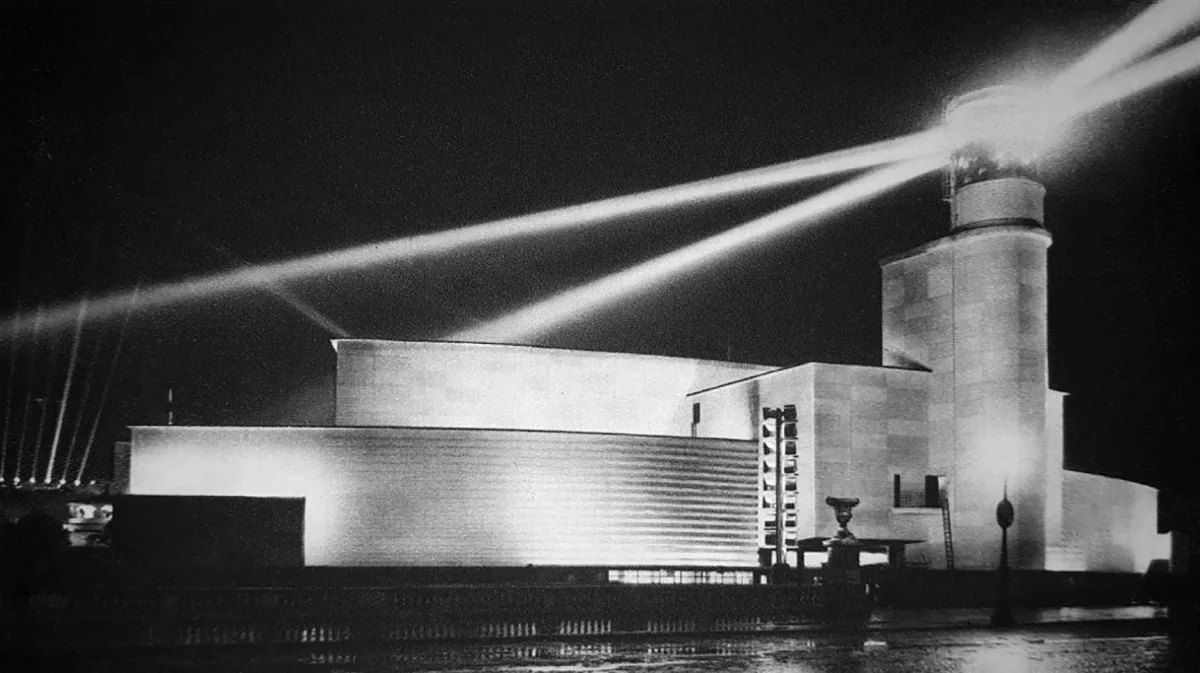

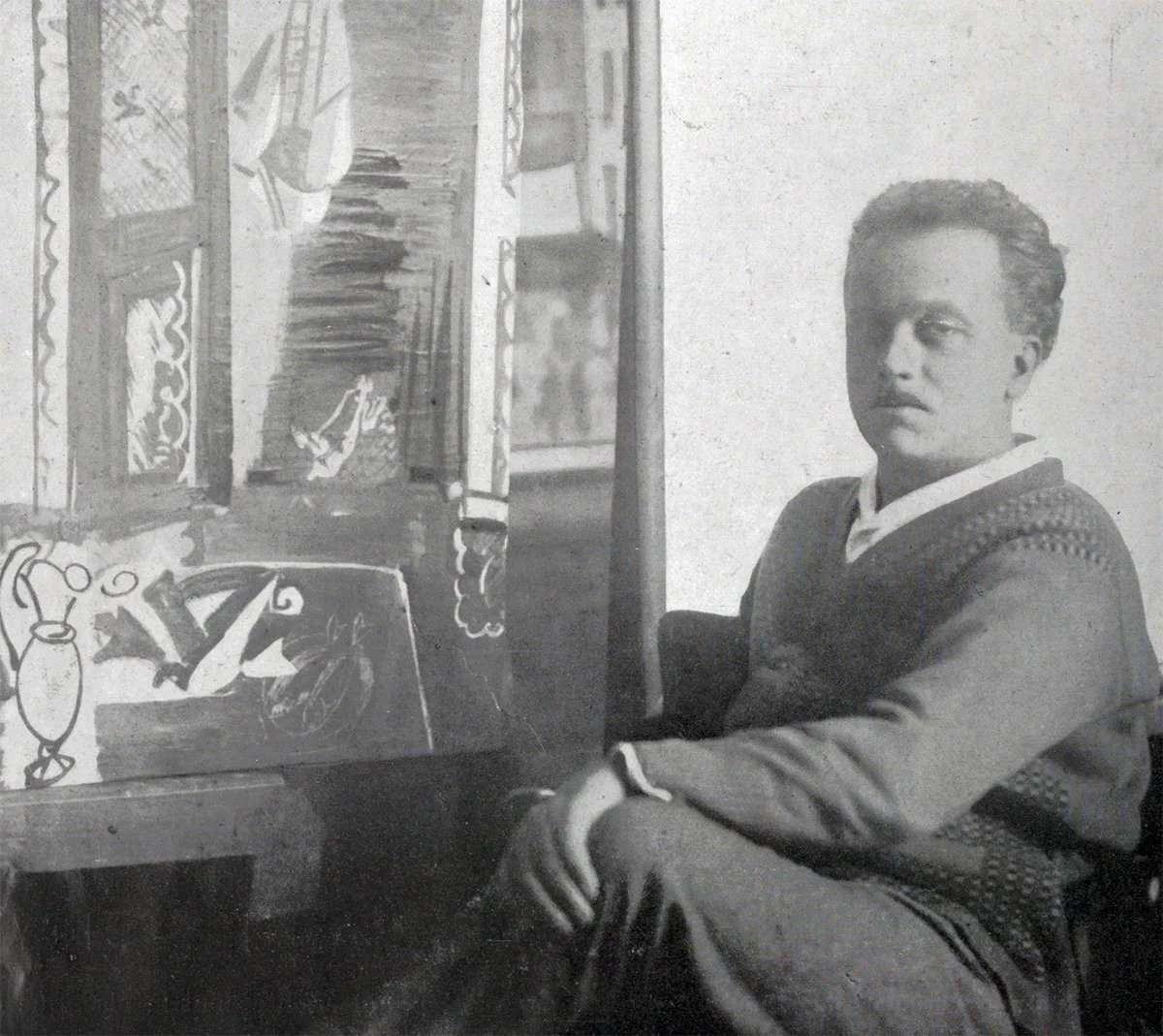

Created by French artist Raoul Dufy (1877-1953) for the Electricity Pavilion at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair, the monumental mural “La Fée électricité” is a celebration of technological progress.

From silk foulard to monumental painting

A naive history of the energised world

Radio as the crowning achievement of electrification

The virtual “Fée électricité”

The Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris has recently launched a virtual presentation of the “Fée électricité”, with detailed explanations in French and English of the people and inventions depicted.

Physicist and philosopher of science Etienne Klein explains the work Fée Électricité YouTube / Musée d'Art Moderne de Paris