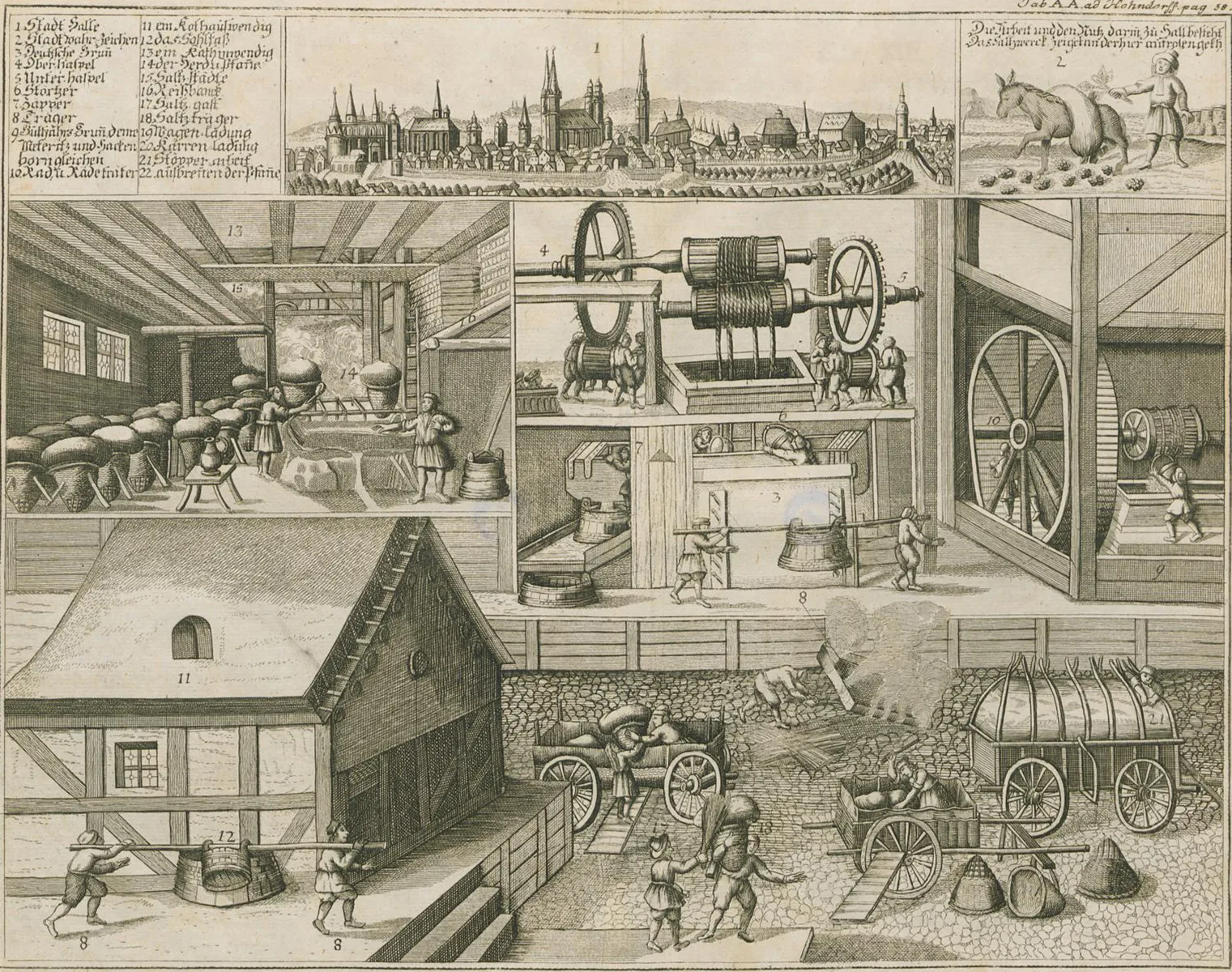

The salt of life

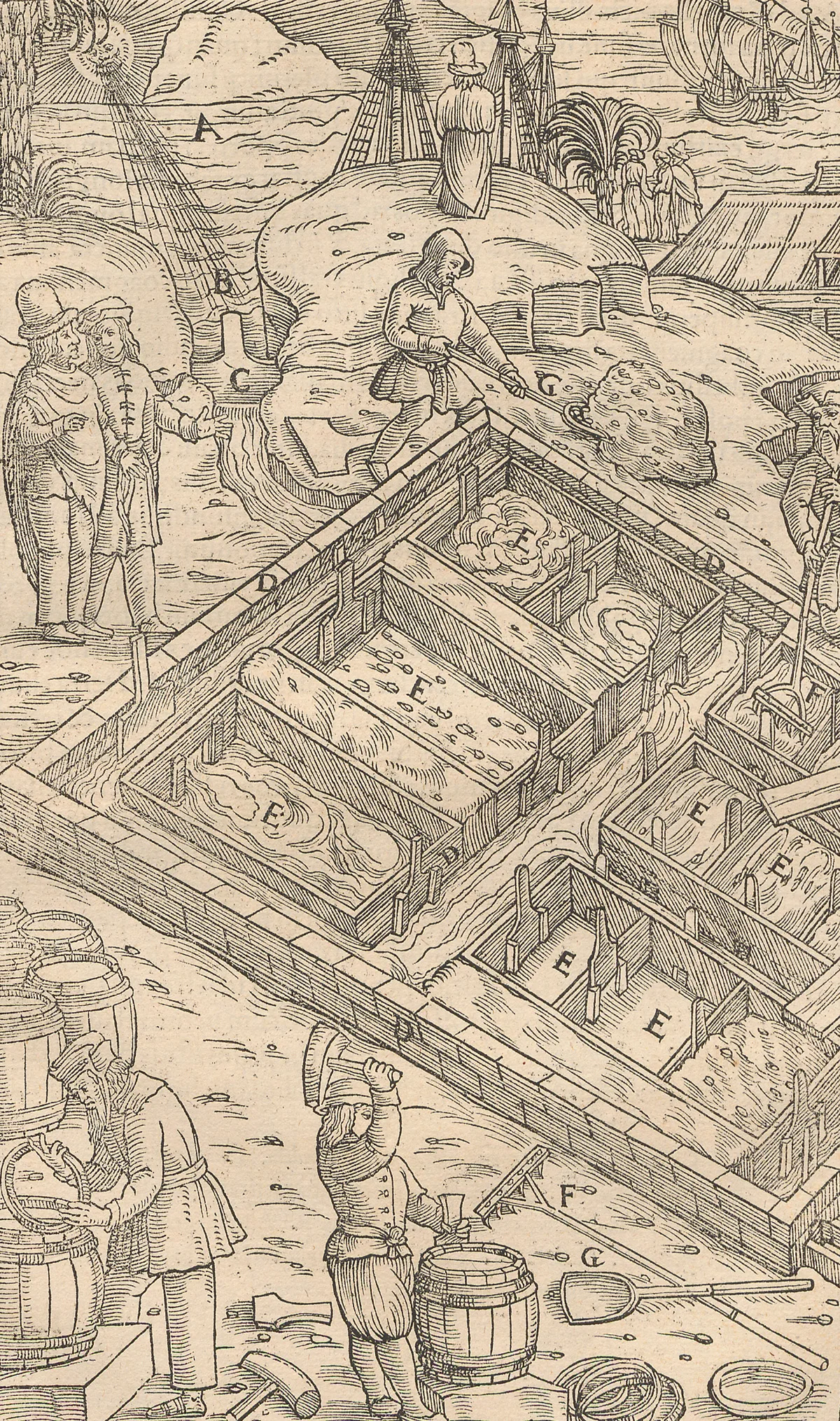

Salt is much more than just a seasoning. Salt is essential to life, and therefore a valuable commodity. For centuries Switzerland was dependent on salt imports. In 1836, a determined German drilling specialist and ‘salinist’ changed that for good.