Swiss National Museum

The image of Switzerland in the time of Gottfried Keller

His, more than any other, was the hand that shaped Switzerland’s image in the 19th century: Zurich-born artist, watercolourist and art publisher Rudolf Dikenmann. His prints produced using the aquatint technique were churned out in their thousands: for travellers, collectors and members of the public.

Through the middle of the still unspoilt Limmat Valley and the fields and meadows of the area outside the city which has been known since 2005 as Zürich-West, a steam train of the Spanisch-Brötli-Bahn line trundles towards the central railway station, built in 1847. A second steam train, heading out of the station, is approaching the viaduct spanning the Limmat, completed in 1856. The journey will take it through the tunnel between Wipkingen and Oerlikon in the direction of Winterthur, and from there to Romanshorn. The view, from the train puffing across the railway bridge, of the town and the Alps was considered by contemporaries to be ‘the highlight of Switzerland’s railways’. The opening of the Swiss Northeastern Railway route from Zurich to Lake Constance was celebrated on 25 and 26 June 1856 with much pageantry, which Gottfried Keller immortalised in a poem composed to mark the occasion: ‘Denn fertig war das Eisenband / Das mit dem deutschen Nachbarland / Am blauen See die alte Stadt / Wegsam und neu verbunden hat.’

View over Zurich from the Weid. Aquatint, partly etched, two-tone print (black/blue). Artist and engraver: Heinrich Siegfried. Publisher: Rudolf Dikenmann. Between 1856 and 1877.

Swiss National Museum

The two steam trains on the route from Zurich to Baden, opened in 1847, and on the route from Zurich to Romanshorn via Winterthur, which came into operation in 1856, are the two main events in this representative image. The same view had already been published by Dikenmann and others before the construction of the curved railway embankment and the viaduct. Now, artist Heinrich Siegfried had placed the new civil engineering structures of the railway line in the picture as visual attractions. The staffage figures in the foreground still have a Biedermeier effect, but it is the potential for growth between Biedermeier and the Wilhelmine period that is striking, both at the time, and from today’s perspective.

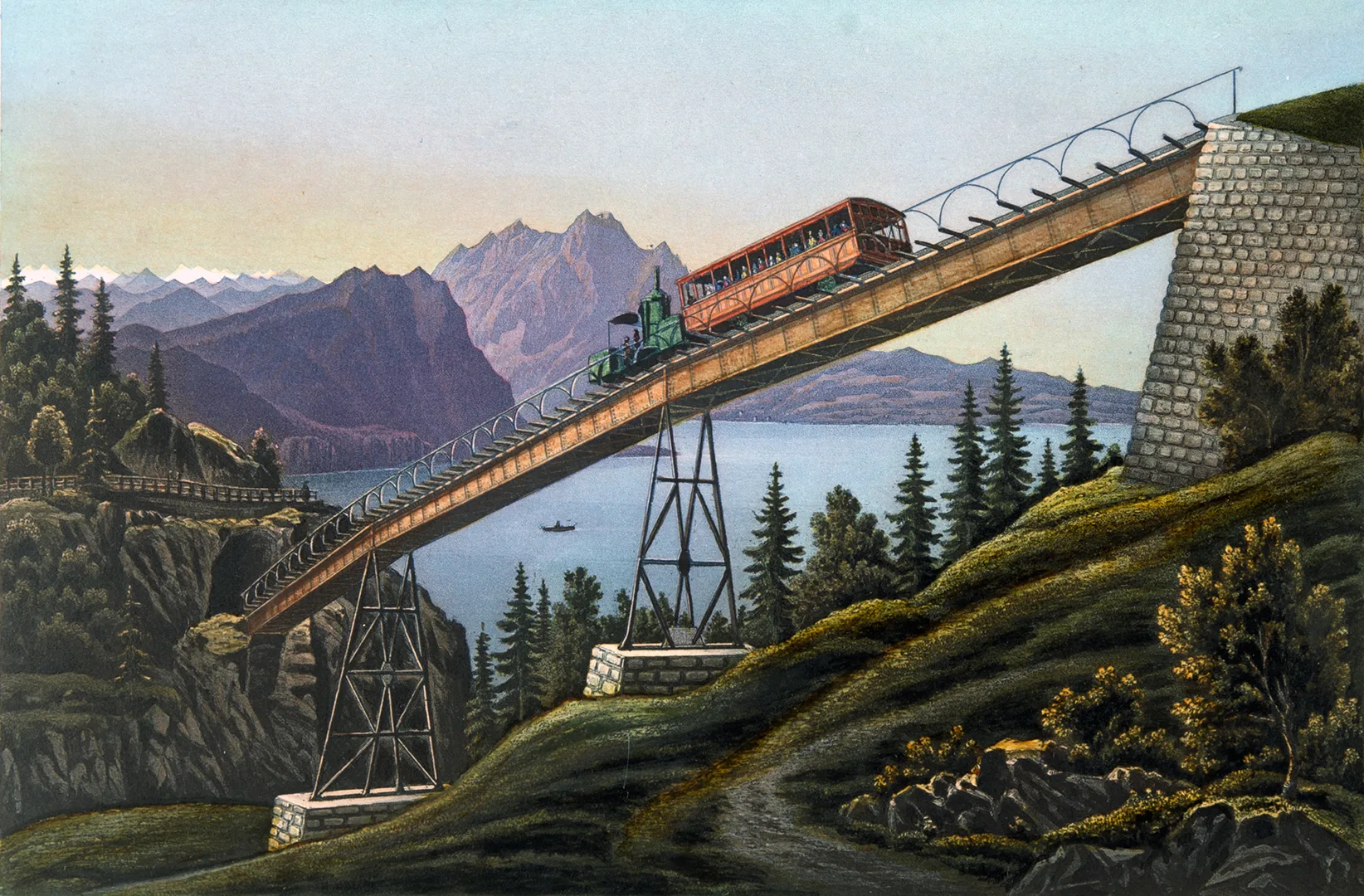

Dikenmann’s art publishing business

The Zurich art publishing company of Rudolf Dikenmann (1793-1884) and his son Johann Rudolf Dikenmann (1832-1888) shaped the image of Switzerland in the time of Gottfried Keller simply because of the sheer volume of the views produced in the Dikenmann studio. The ‘engravings’ were produced from sketched originals, using the aquatint technique. They came on to the market in their thousands: in petit or folio format, as vignettes on notepaper, as a simple black print or as a two-tone print in blue/black. Some of the high-quality typographic prints were coloured by hand by Dikenmann’s daughters Anna and Louise, and by his younger brother Johannes. Rudolf Dikenmann, who had worked for Peter Birmann in Basel after completing his apprenticeship with Orell Füssli & Co. in Zurich, still had all the ‘Kleinmeister’ (‘Little Masters’ school of engravers) expertise, even though the Kleinmeister era was over. The Dikenmann art publishing house was the last manufactory and family business of its kind. The photochromic printing process developed in Zurich, and used at Orell Füssli from 1888, was already presaged in the rich colours, evocative of enamel painting, of the later prints.

View over Lake Geneva. Aquatint, hand-coloured two-tone print. Watercolour sketch by Rudolf Dikenmann. Aquatint, two-tone print. Aquatint, hand-coloured two-tone print.

Swiss National Museum

By coincidence, from 1852 Dikenmann’s studio and business premises were located at Rindermarkt 14, in close proximity to the house Zur Sichel at Rindermarkt 9 in which Gottfried Keller (1819-1890) spent nearly 30 years of his life. In his partially autobiographical novel Green Henry (Der grüne Heinrich), in the chapter ‘The Beginning of Work’, Keller sketches a vivid picture of the mass production of souvenir pictures with the aid of young colourists. Keller, who himself spent a year as an apprentice to a ‘painter of art’ without learning anything, harboured a marked aversion to the work of the ‘colourists’ and to ‘tourist pieces’. The description of the ‘fantastical nightmares of art’ in the studio of the fictitious master Habersaat in Green Henry may be a caricature, but it gives a glimpse into the layout and the work processes in such a manufactory operation.

Gottfried Keller: Green Henry. Chapter 5: The Beginning of Work

“He was a painter, engraver, lithographer and printer in one person, drawing in an outmoded fashion the oft-visited Swiss landscapes, scratching them into copper, printing them, and having some young people paint them with colours. He dispatched these prints all over the world, and had a gratifying trade in them. (…). The main body of this army consisted of four to six young people, some of them mere boys, who coloured in the Swiss landscapes in bright vibrant colours; then came a sickly, coughing fellow, who smeared resin and nitric acid on small copper plates, and let fearful holes eat in, stabbed between them with the etching needle and was called the engraver. (…) Finally, at the back of all the crowd and overlooking all, sat the master, painter and art dealer Habersaat, proprietor of a copper and lithographic printing house and at the disposal of all who wished to engage him for any purpose, at his table with the finest and most difficult tasks, but mostly busy with his books, letter writing and packaging of finished things.”

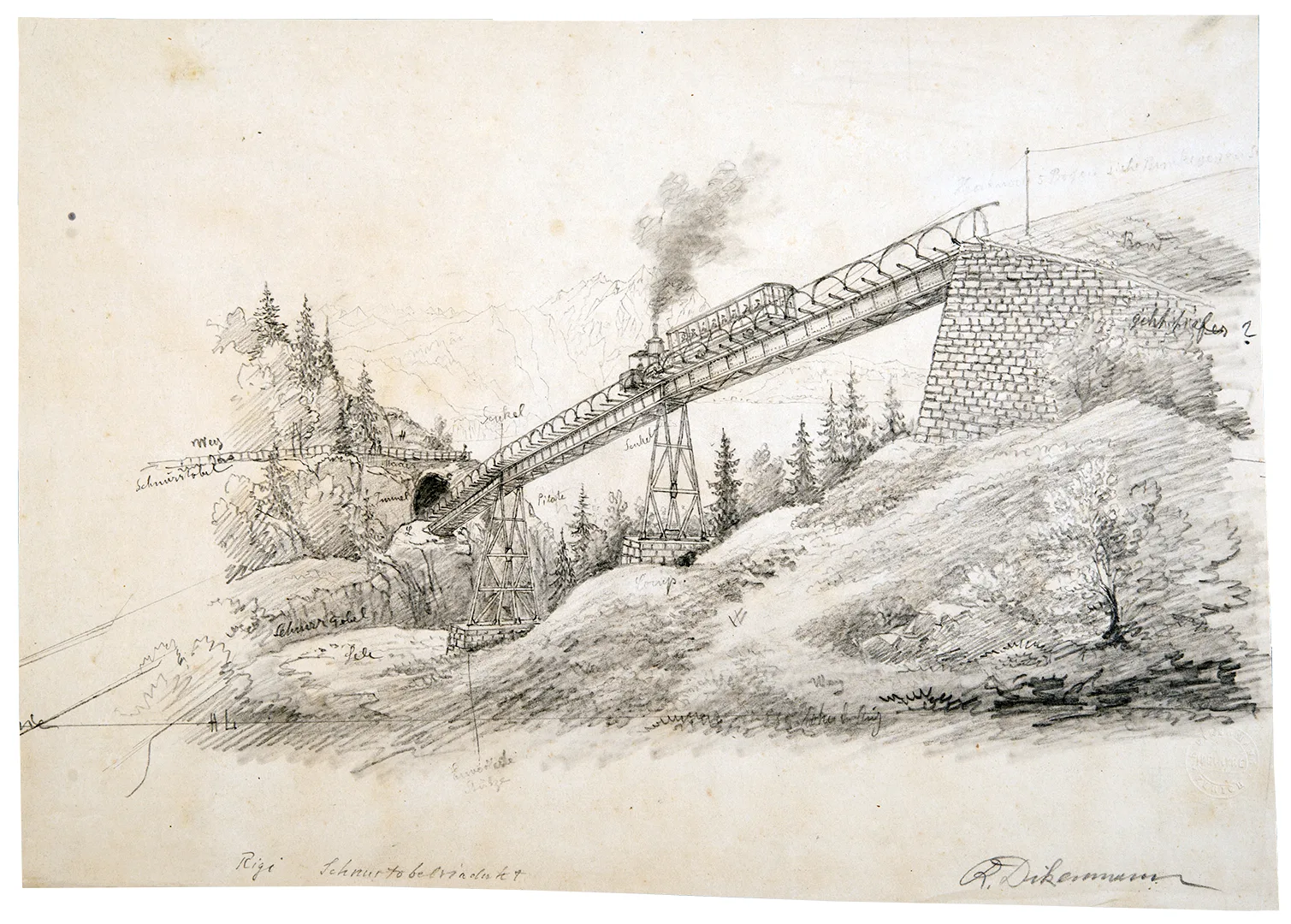

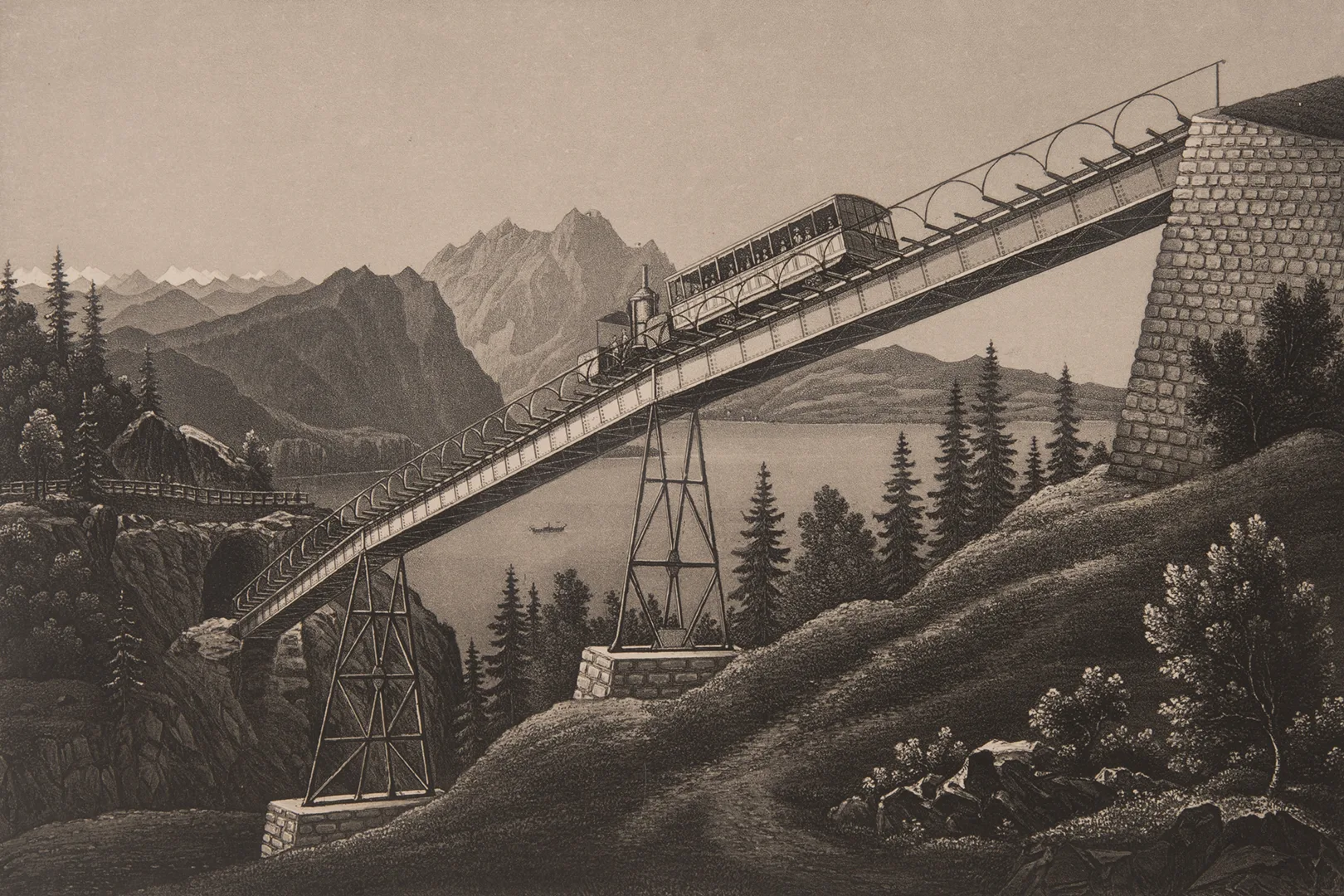

The Vitznau-Rigi railway on the Schnurtobel bridge

One of the most-visited destinations in Switzerland in the Wilhelmine period was the Rigi, with its Rigibahn, opened in 1871 as Europe’s first mountain railway. The journey over the Schnurtobel bridge in the rack railway train, described by Mark Twain in 1878 in his travel memoire A tramp abroad, must have been a heart-stopping experience: ‘We got front seats, and while the train moved along about fifty yards on level ground, I was not the least frightened; but now it started abruptly downstairs, and I caught my breath. And I, like my neighbors, unconsciously held back all I could, and threw my weight to the rear, but, of course, that did no particular good. (…). By the time one reaches Kaltbad, he has acquired confidence in the railway, and he now ceases to try to ease the locomotive by holding back. (…). There is nothing to interrupt the view or the breeze; it is like inspecting the world on the wing. However – to be exact – there is one place where the serenity lapses for a while; this is while one is crossing the Schnurrtobel Bridge, a frail structure (…). One has no difficulty in remembering his sins while the train is creeping down this bridge.” It is no wonder that the locomotive, with its vertical boiler and open passenger carriages, crawling down the Schnurtobel bridge became a popular subject for souvenir pictures. Rudolf Dikenmann sketched the scene in around 1880, as a template for its production as an aquatint.

The Rigi Railway on the Schnurtobel bridge. Sketch by Rudolf Dikenmann. Aquatint, black print. Aquatint, hand-coloured two-tone print.

Swiss National Museum

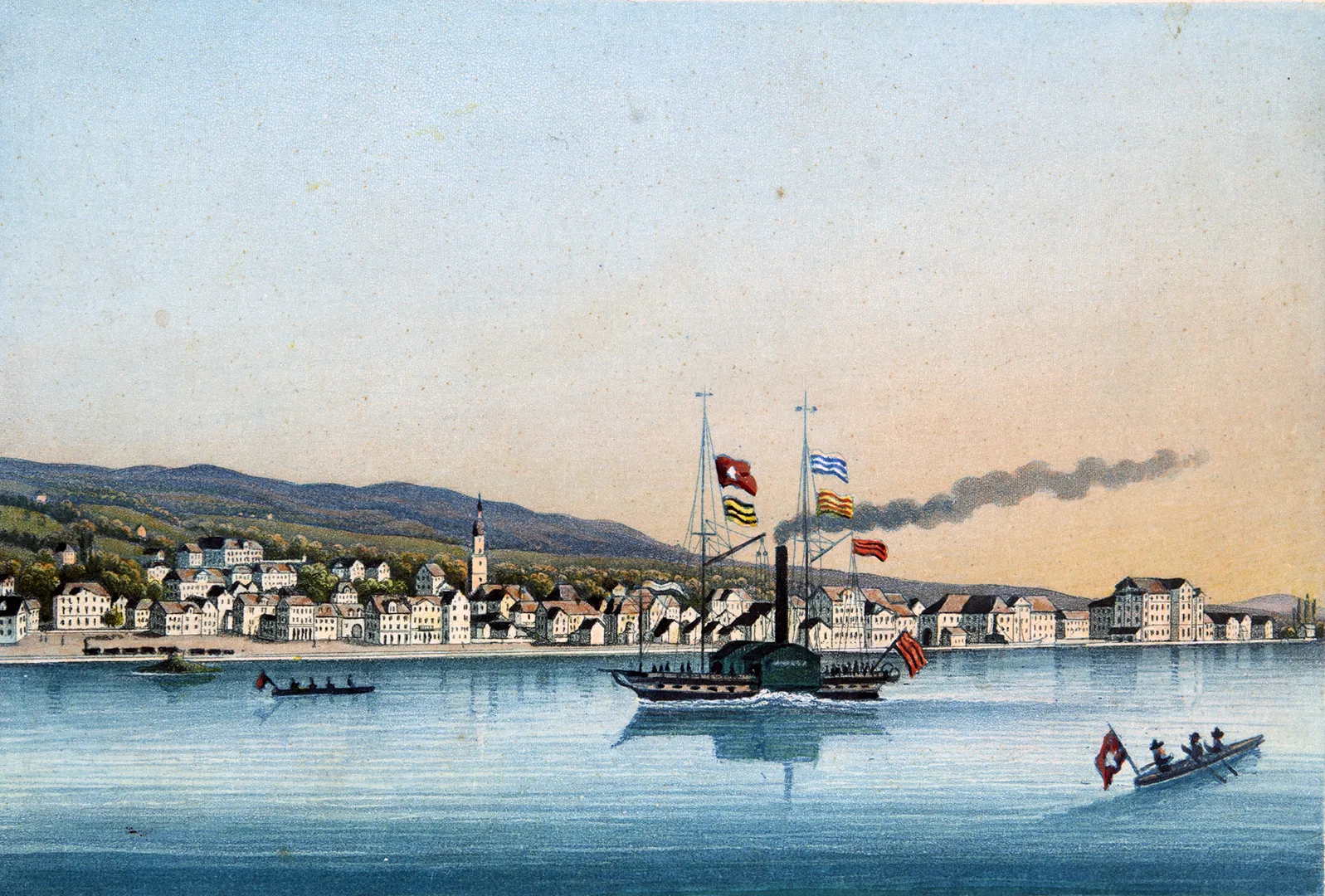

Parade of boats near Rorschach

One particularly attractive print from the estate of the Dikenman Kunstverlag depicts three paddle-steamers on Lake Constance. The artist is Rorschach landscape painter and publishing associate Joseph Martignoni. The 1850 drawing, painted in watercolours, served as an engraver’s template. On the left of the picture is the Stadt Schaffhausen, the first Swiss steamship on Lane Constance, and in the centre is the flush-deck paddle steamer Kronprinz, which was brought into service in 1838. The Kronprinz was Württemberg’s second Lake Constance steamer, and the first Lake Constance vessel built by Escher Wyss in Zurich. The vessel on the right of the picture is probably the Baden ship Stadt Constanz, although it is shown flying Bavarian colours. In Rorschach the lines of the United Swiss Railways from St. Gallen and Chur, opened in 1856 and 1858 respectively, connected with shipping traffic to Germany.

At Rorschach on Lake Constance. Watercolour sketch. Aquatint, hand-coloured two-tone print. Aquatint, hand-coloured two-tone print.

Swiss National Museum