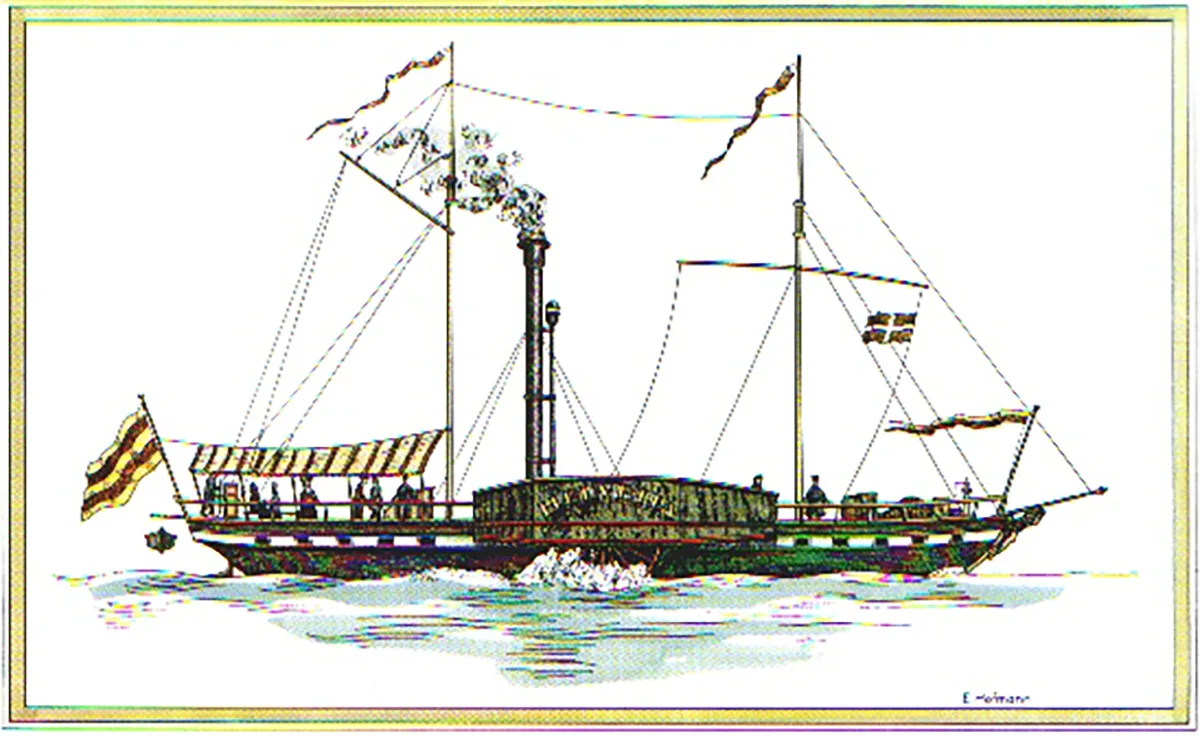

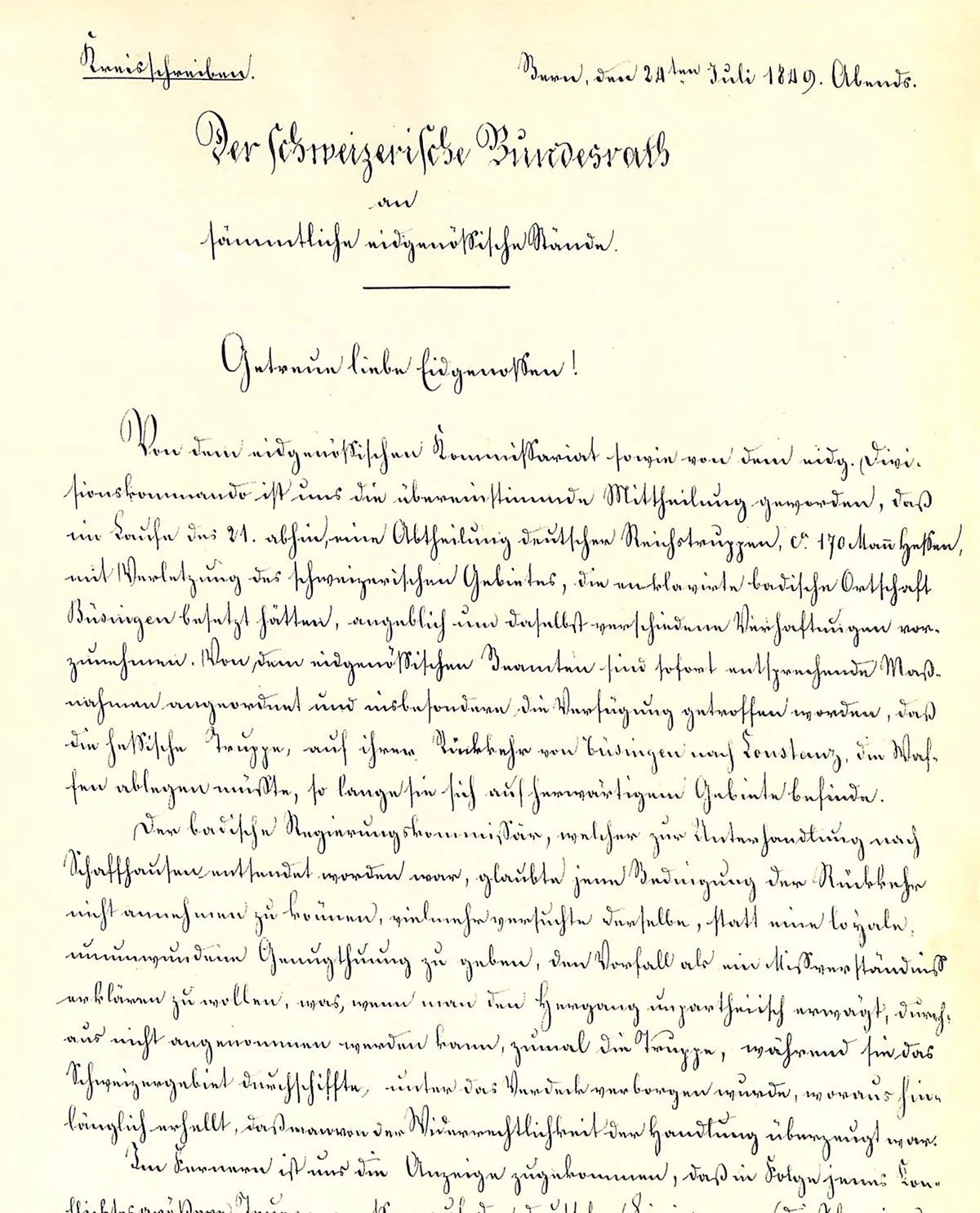

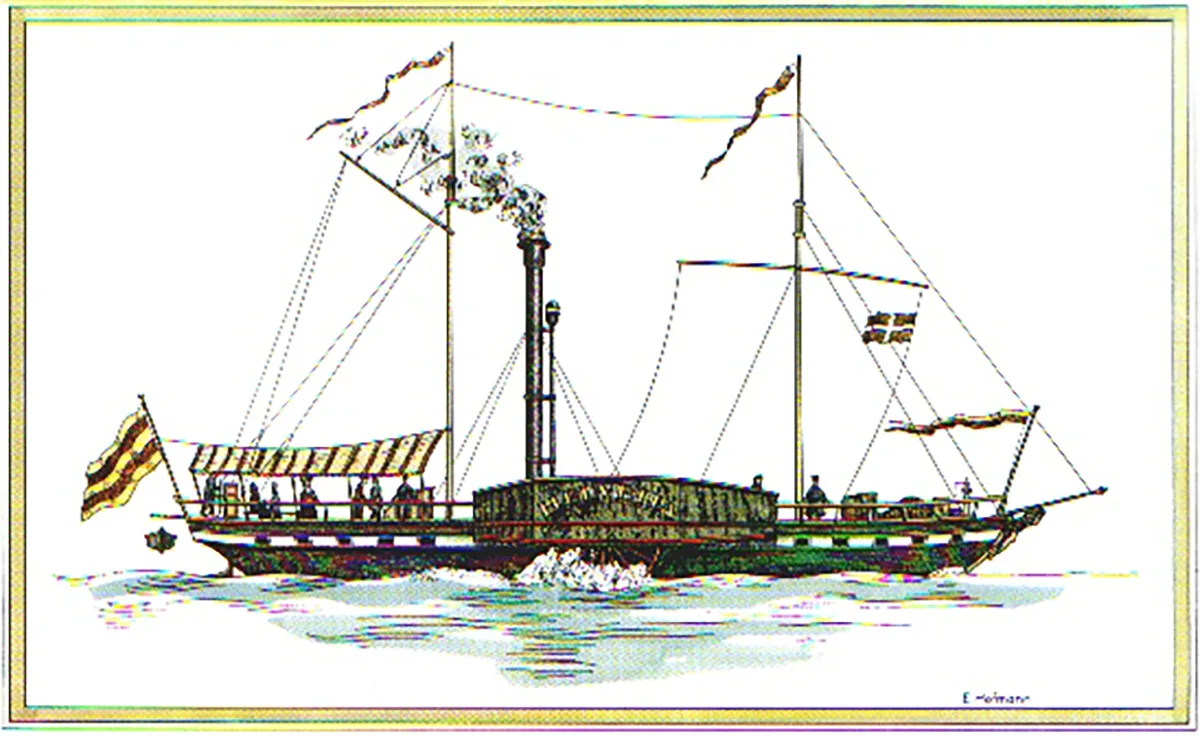

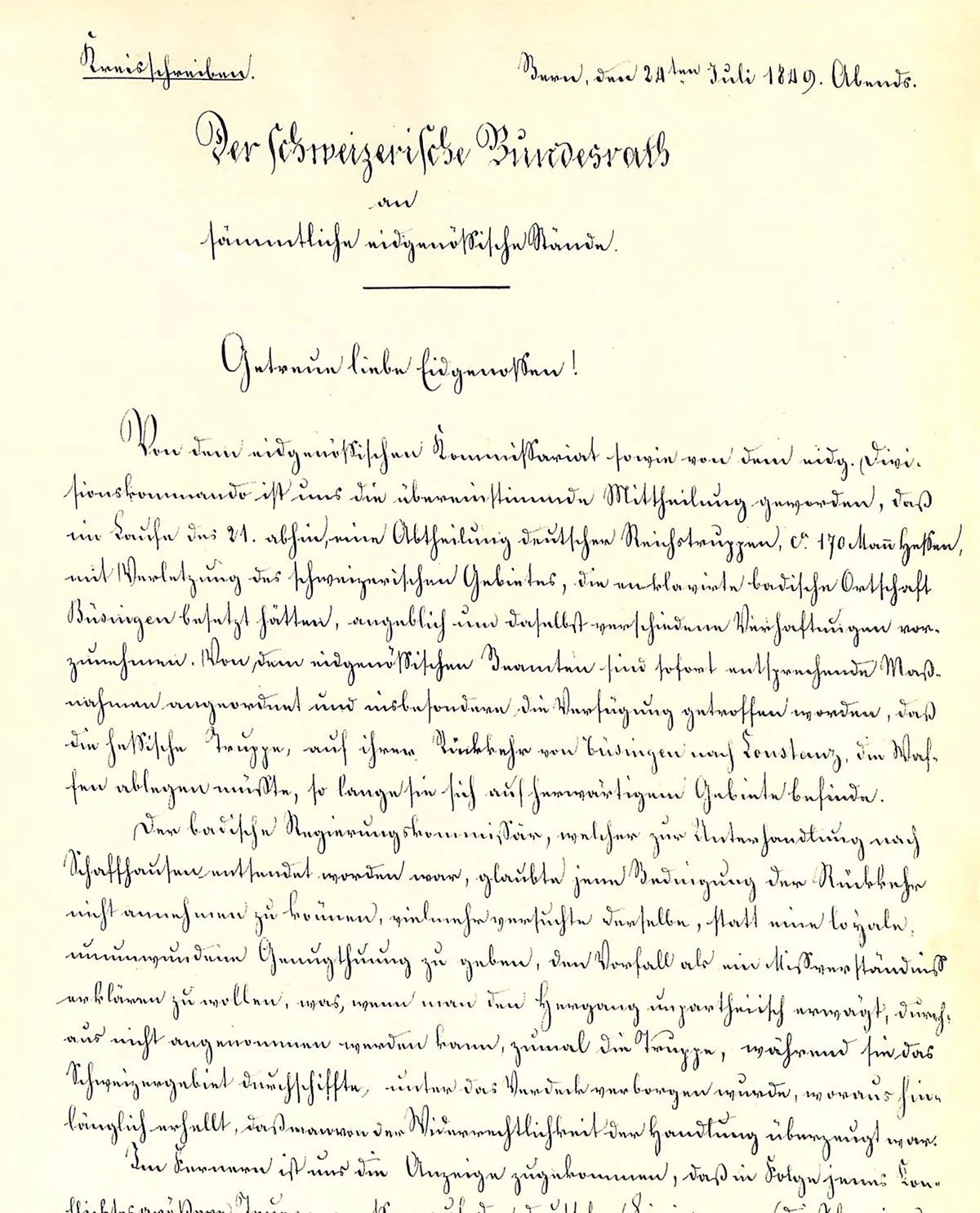

The Büsingen Affair

Schaffhausen was the scene of some serious sabre-rattling between Hessian soldiers and Swiss troops in July 1849. It took cool-headedness and negotiating skill to avoid a bloody conflict.

The Swiss army on standby

Schaffhausen was the scene of some serious sabre-rattling between Hessian soldiers and Swiss troops in July 1849. It took cool-headedness and negotiating skill to avoid a bloody conflict.