Nema – a Swiss cipher machine

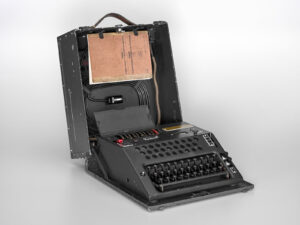

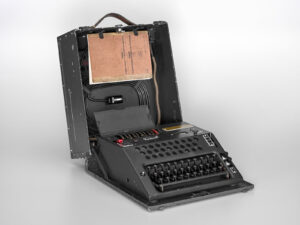

During the Second World War, Switzerland developed a better cipher machine than Enigma: Nema.

Demonstration of a German Enigma device. Youtube

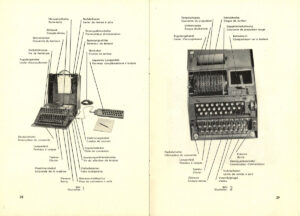

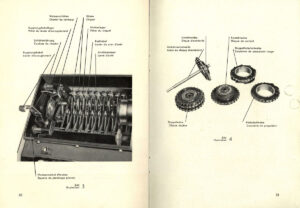

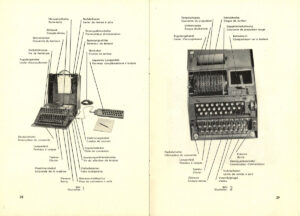

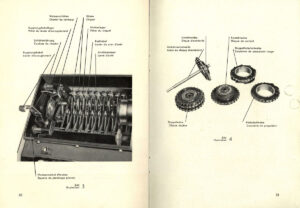

The Nema manual, which came out in 1948. Swiss Federal Archives

During the Second World War, Switzerland developed a better cipher machine than Enigma: Nema.