A ‘light-spitter’ lights up the skies

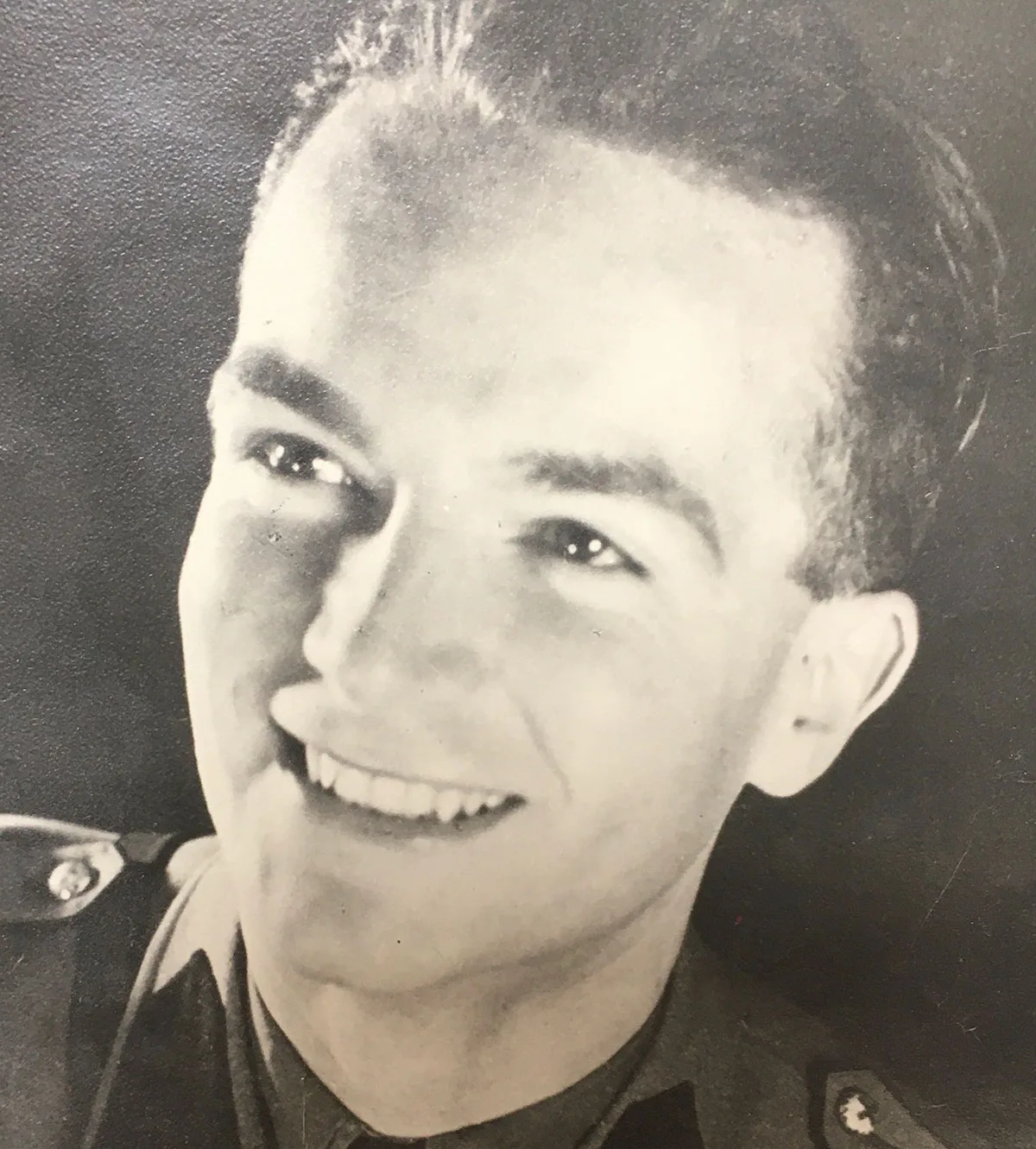

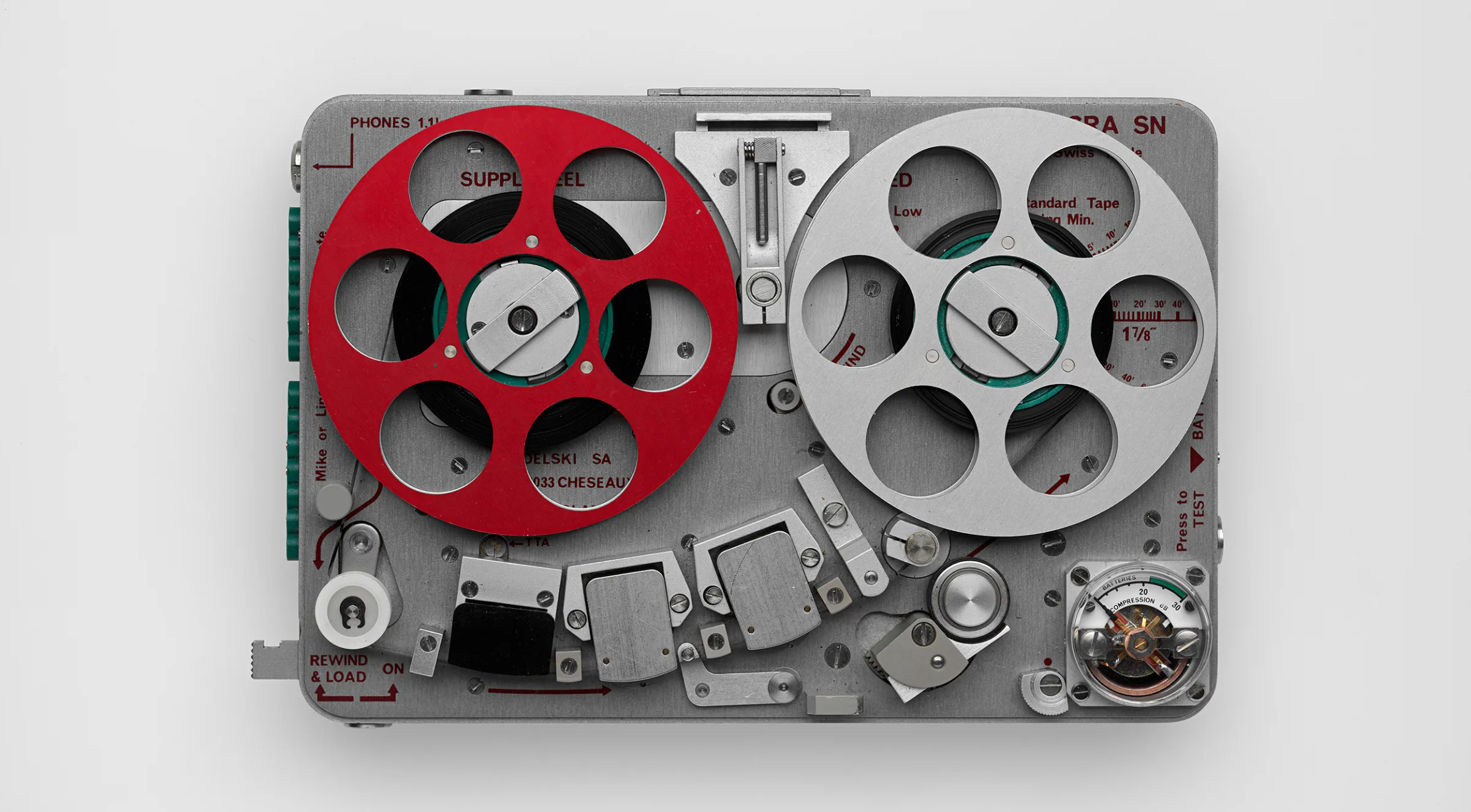

It caused a sensation in 1955 – the Spitlight, a light beam device that could project images onto cliff faces and clouds. But the futuristic device brought no joy for its inventor.

The projector’s long odyssey

A TV report from 1982 featuring archive images from the 1950s (in German). YouTube / Schweizer Fernsehen