Using the ‘magic formula’ to achieve concordance

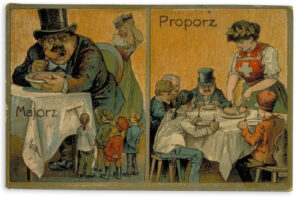

Concordance is a model of democracy that promotes consensus and ensures internal peace, and it is a hallmark of Switzerland’s political system. The system came into being at the beginning of the 20th century.

Historical roots

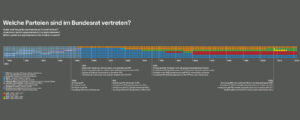

The ‘magic formula’ of the Federal Council

Great political importance