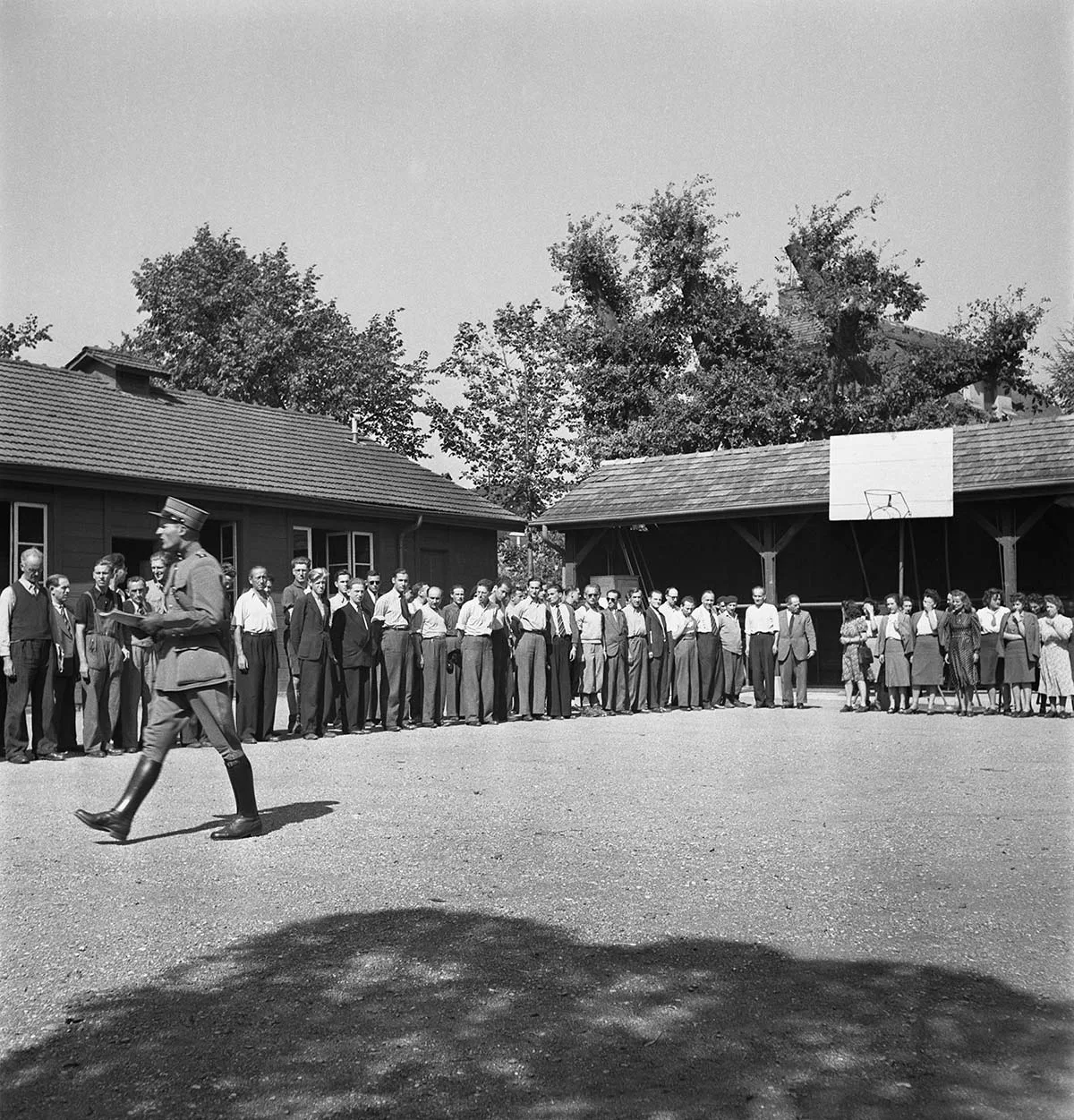

Finding sanctuary in Geneva

During World War II, hundreds of Jews fled from France into Switzerland via Geneva. After the border was closed in August 1942 this escape route became more difficult to navigate, but not impossible, as the stories of Lilian Blumenstein and Lili Reckendorf show.