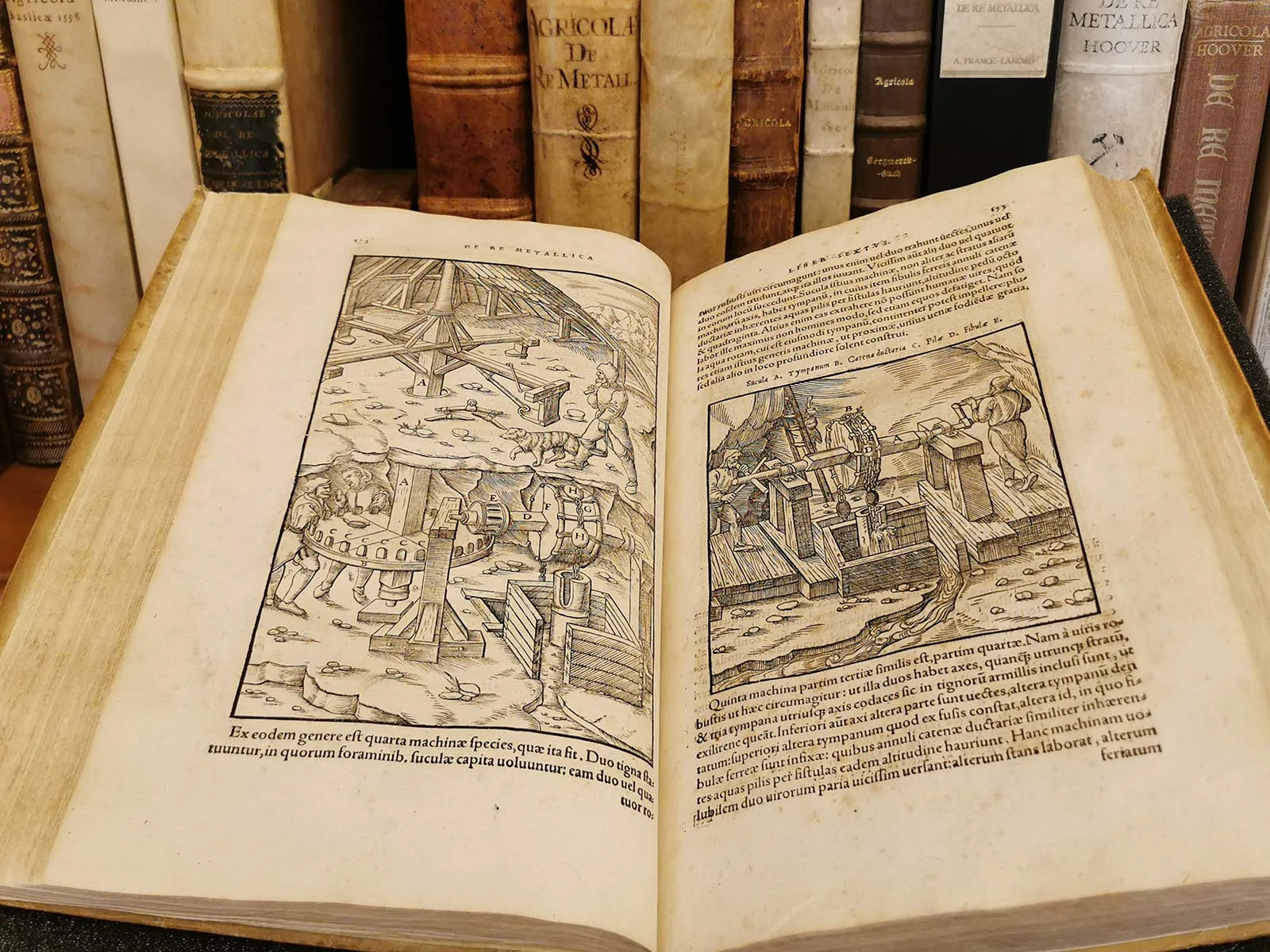

De re metallica – a 16th-century bestseller

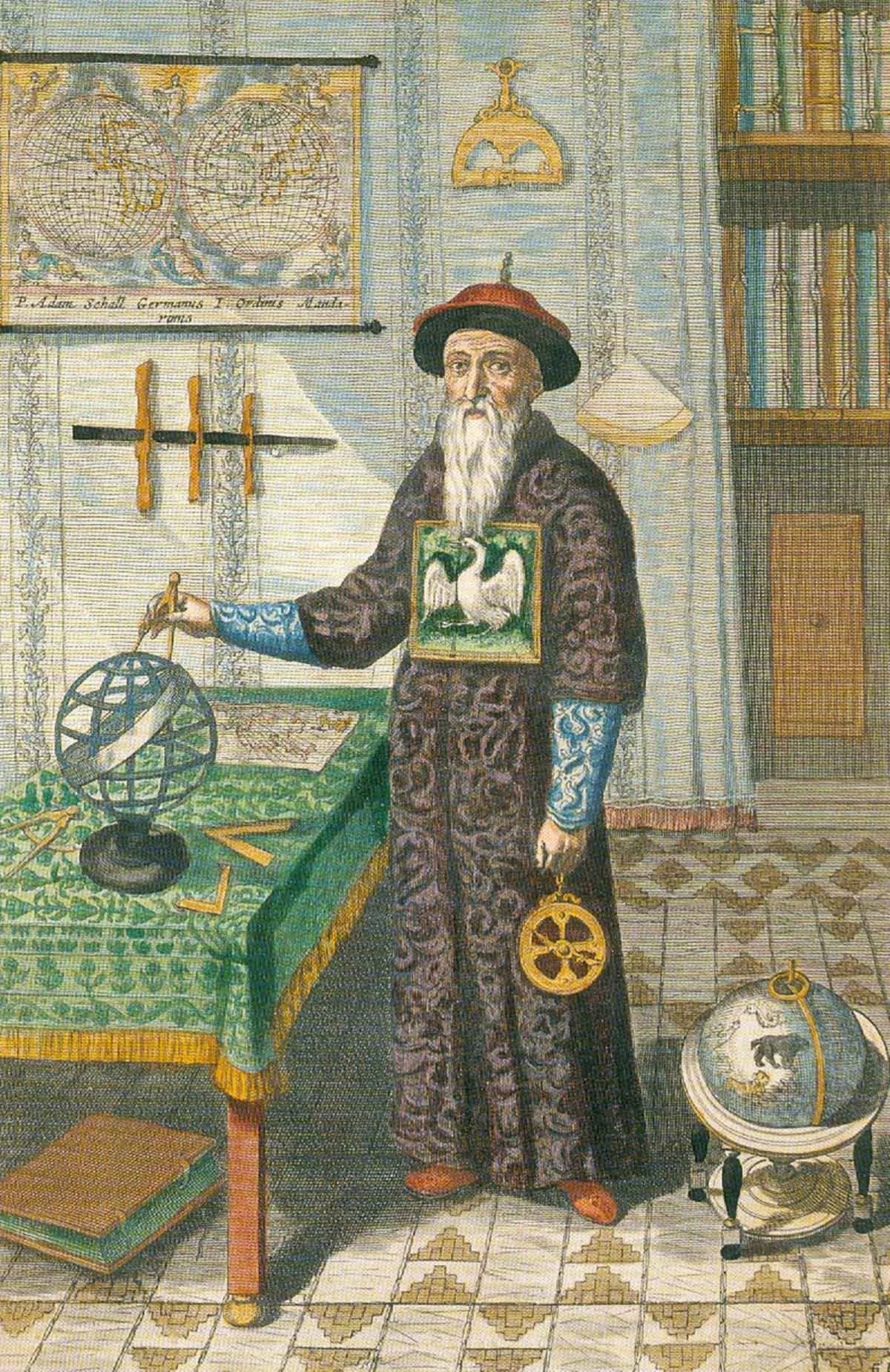

How a Chemnitz doctor revolutionised mining, and why he had his book printed in Basel… The story of Georg Bauer, better known as Georgius Agricola.

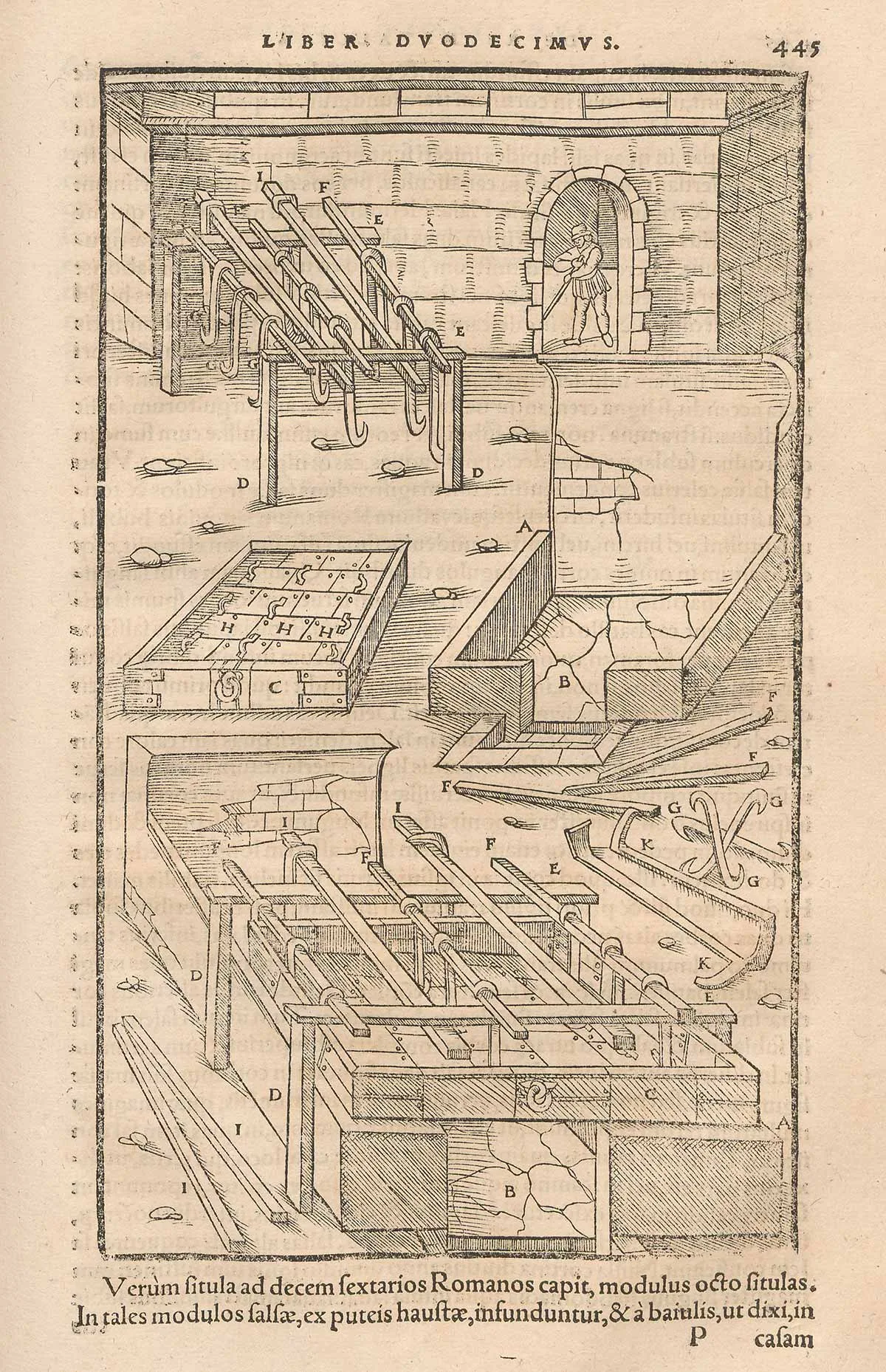

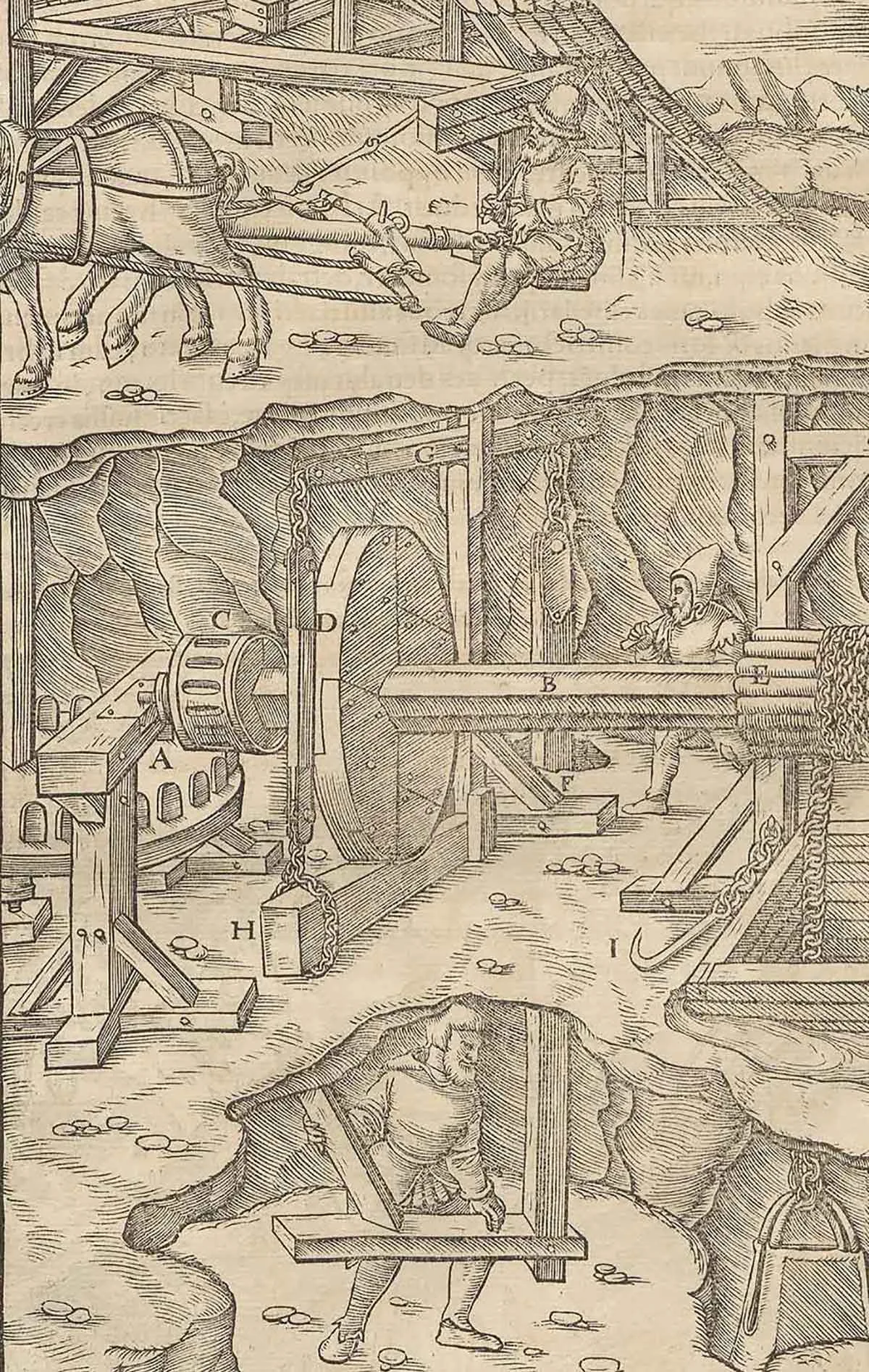

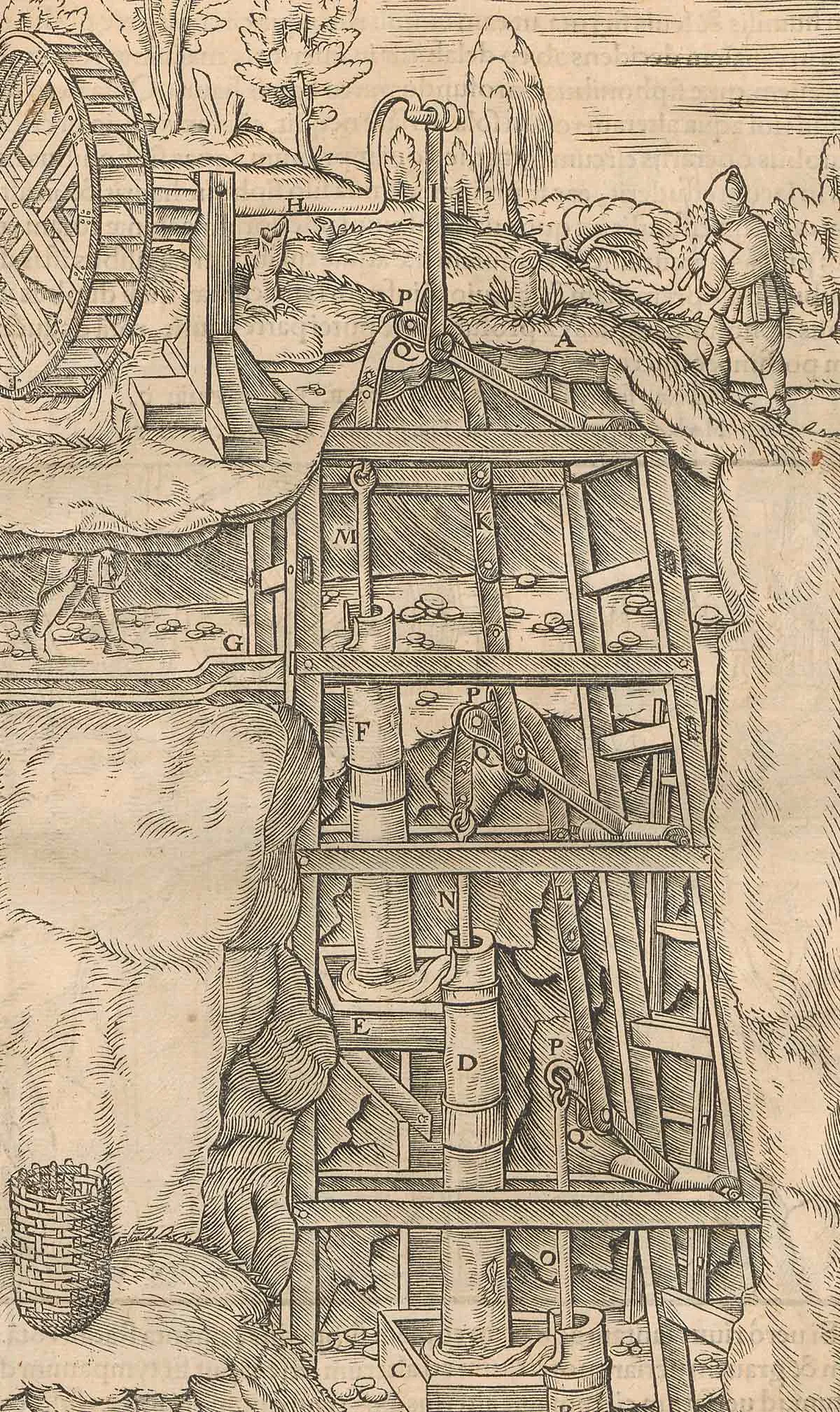

The highly detailed woodcuts contributed to the book’s success. ETH Library Zurich