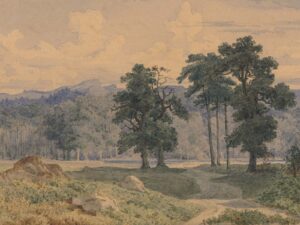

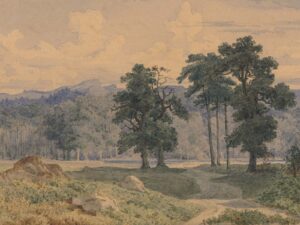

Keller’s love for the oak tree

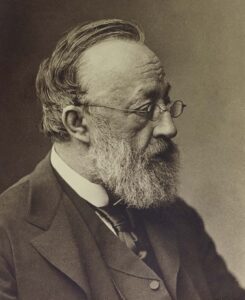

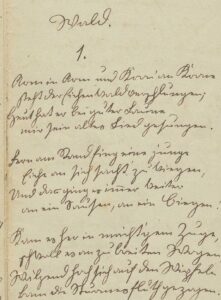

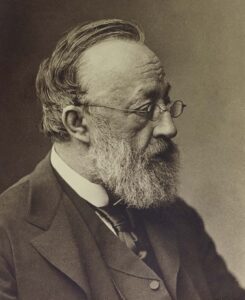

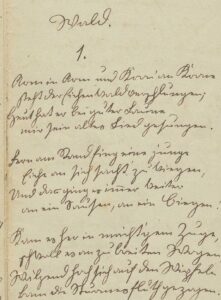

Gottfried Keller’s most ardent desire was to become an artist and paint scenes of nature. In the end he did just that, but mostly in words.

Gottfried Keller’s most ardent desire was to become an artist and paint scenes of nature. In the end he did just that, but mostly in words.