In praise of work

On Labour Day, we celebrate the glories of work. We raise a glass to the workers, but also to the chroniclers, artists and photographers. The pictorial sources they created show people at work throughout the centuries.

1. Working in the fields

The wheeled plough, a breakthrough in agricultural technology: at the front the wooden wheel frame, and behind it the iron plough blade, which slices into the soil vertically and, together with the iron mouldboard, pushes up whole clods of earth and turns them over – beneficial for nutrients and sowing of seeds. The crop is harvested with the sickle and ground in the mill, which is driven by the waterwheel. Sachsenspiegel, ca. 1230. Heidelberg University Library

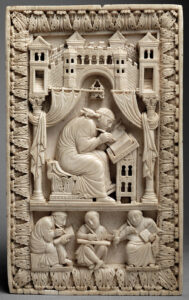

2. Clerical work

3. Construction

4. “Martine, my dear sir, fill our cups to the brim!”

5. Teamwork

6. “No tears in their sombre eyes. They sit at the loom and bare their teeth.”

7. Discipline on the factory floor

8. Two sides of the same coin

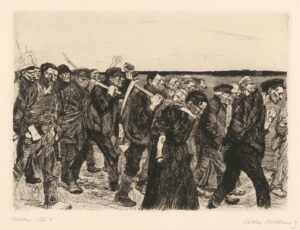

9. “This is our handiwork!”

10. What is work? What is life?