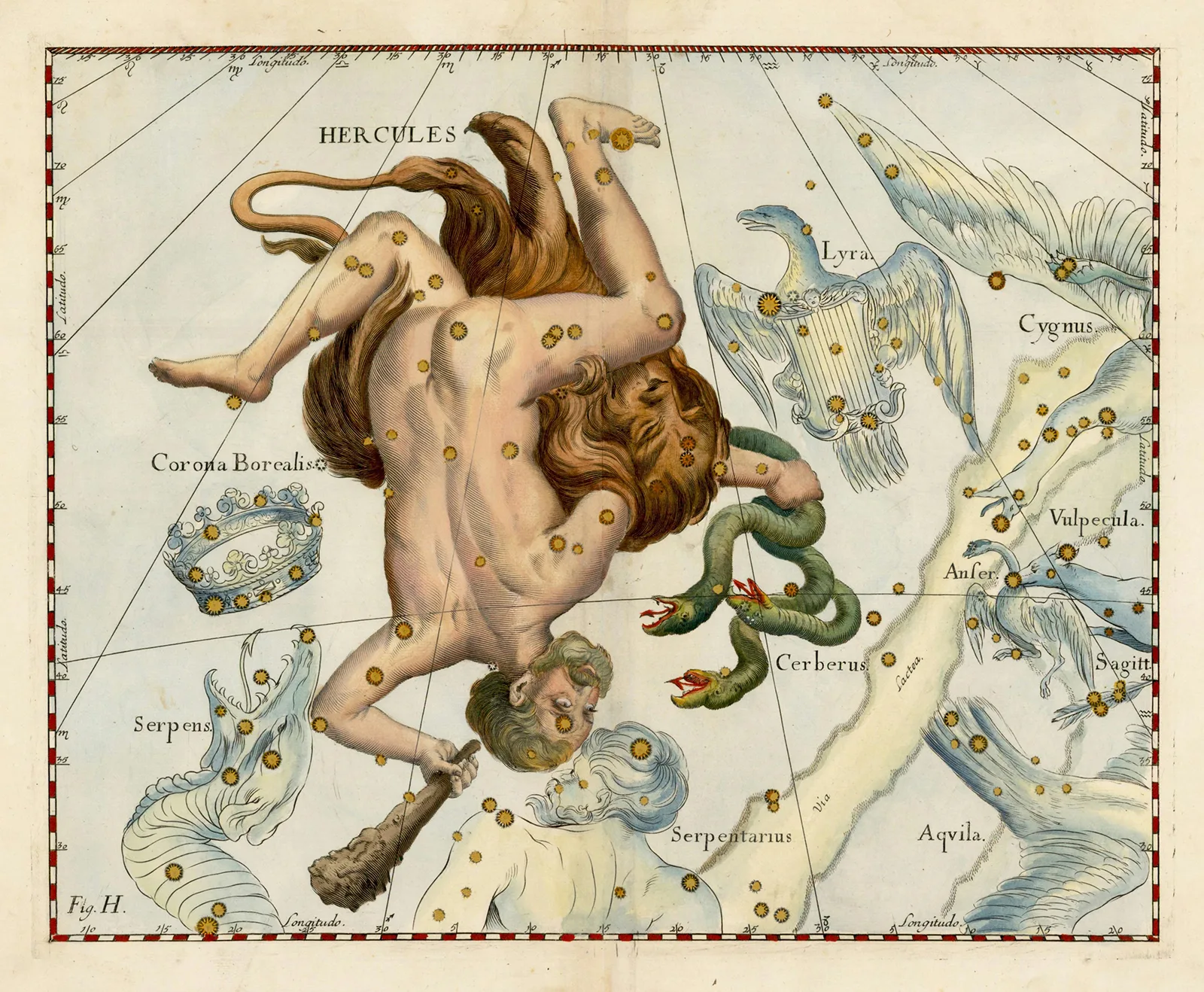

Greetings from Heracles

The Greek myths are a treasure chamber of human possibilities and limits. A little foray into the life of Heracles, the greatest hero of them all, provides ample evidence of this. The setting is archaic and mythical; the knowledge gained is ageless.

The fight with the Nemean lion

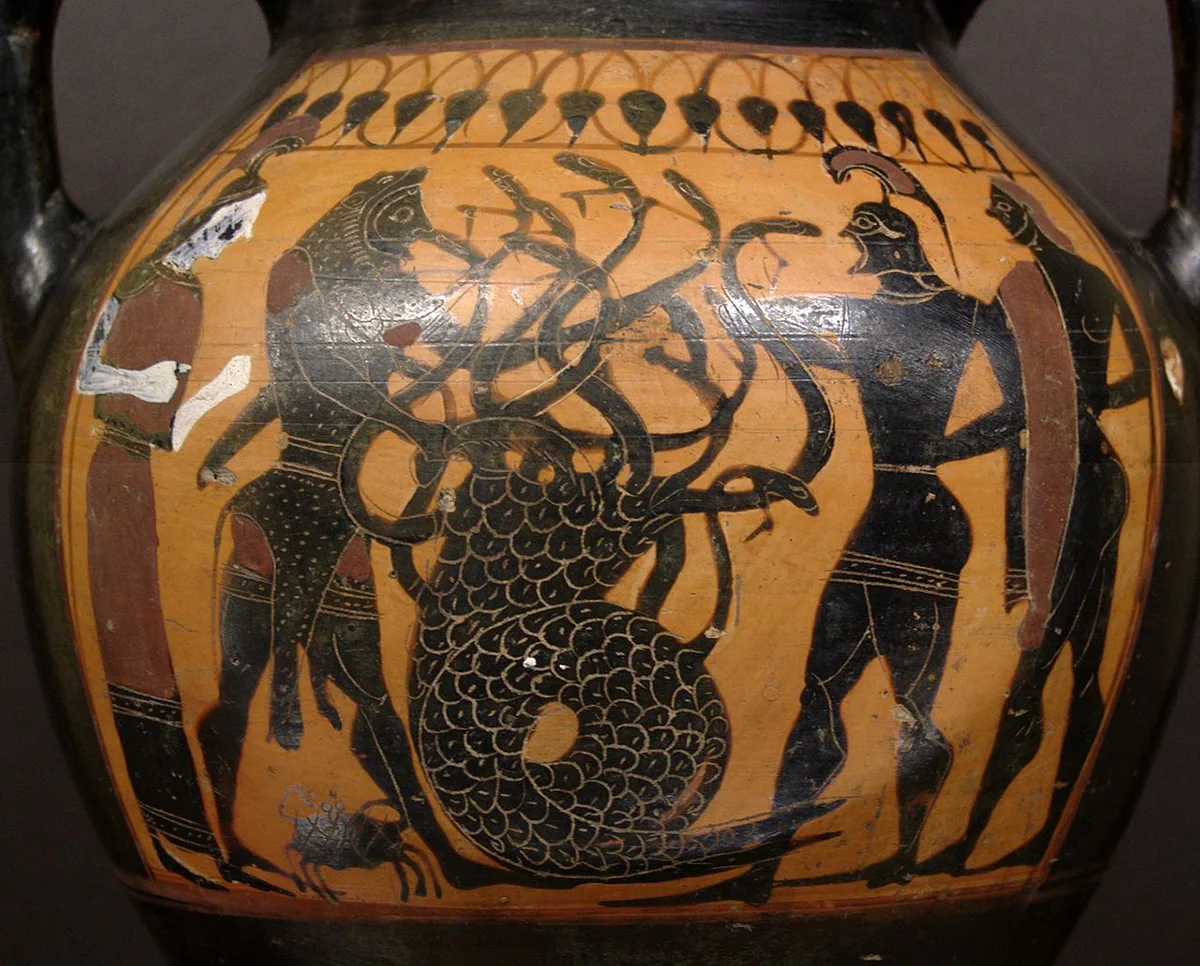

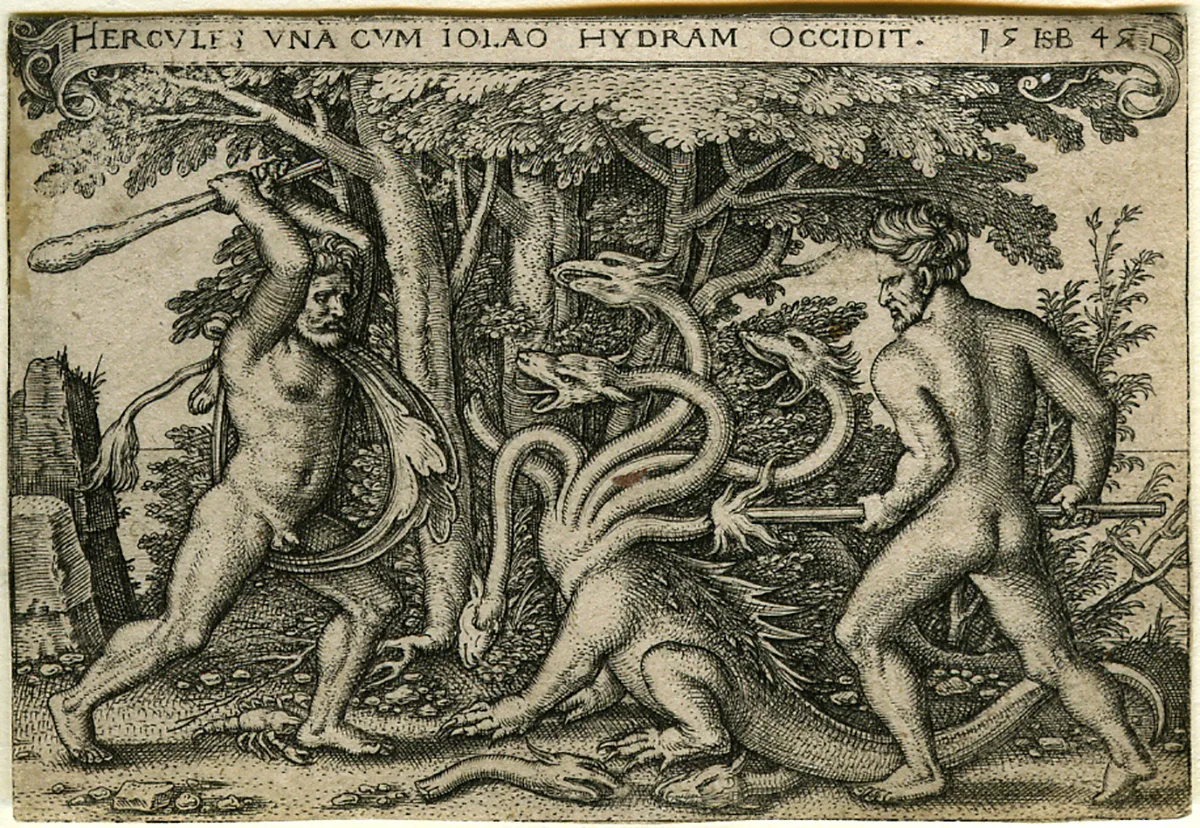

The battle with the Lernaean Hydra

The Augean stables

Vive la différence!

A lovelorn hero

A business as good as the pictures

Have a good trip!