The exhausted man

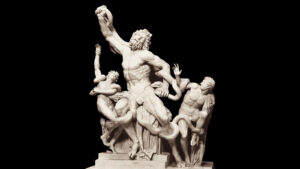

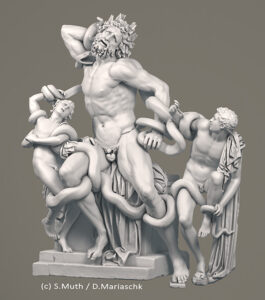

The ancient sculpture of Laocoön and his sons is a turning point in the artistic representation of man – but the piece is also an object of projection for constantly changing ideals of masculinity.

The exhausted man

For centuries, ideals of masculinity have swung back and forth between invulnerable strength, and weaknesses laid bare. The fourth exhibition by the two guest curators Stefan Zweifel and Juri Steiner at the National Museum takes a stroll through the European cultural history of mankind. Its traces can be found through the ages, in art, history, literature and cinema.