Madame Palatine at the court of the Sun King

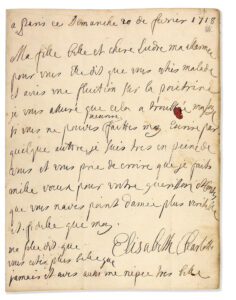

Liselotte von der Pfalz’s extensive correspondence gives something of an autobiographical portrait of its writer, provides a no-holds-barred chronicle of the French court at the time of Louis XIV and the Régence, and is one of the best-known German-language texts of the Baroque period.

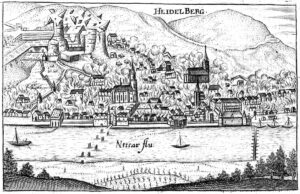

From Heidelberg to Versailles

Liselotte’s life at the French court

“Being Madame is a miserable job”

Free of pretensions and artifice

In conflict with the beloved King

From widow to mother of the Regent

Death and afterlife