The dancing Sun King

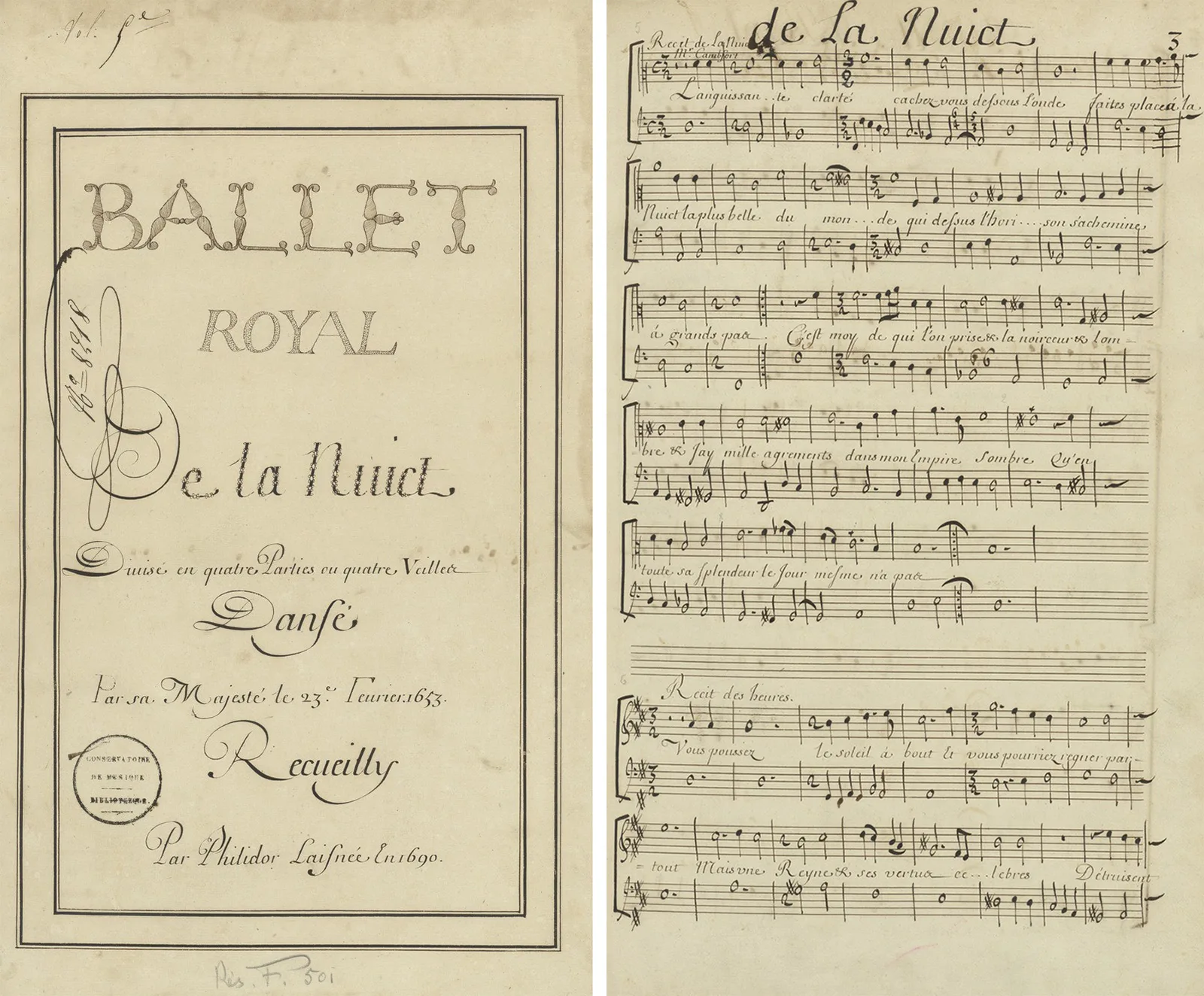

French king Louis XIV liked to use dance as a way of projecting his absolute power. A year before his glorious coronation, he embodied the rising sun – dressed as the sun god, Apollo – in the centre of the planetary system.

An allegory of the victorious kingdom

Triumphant performance as the sun god

Clip from the film "Le roi danse" (‘The King is Dancing’), 2000. YouTube

The birth of the Sun King