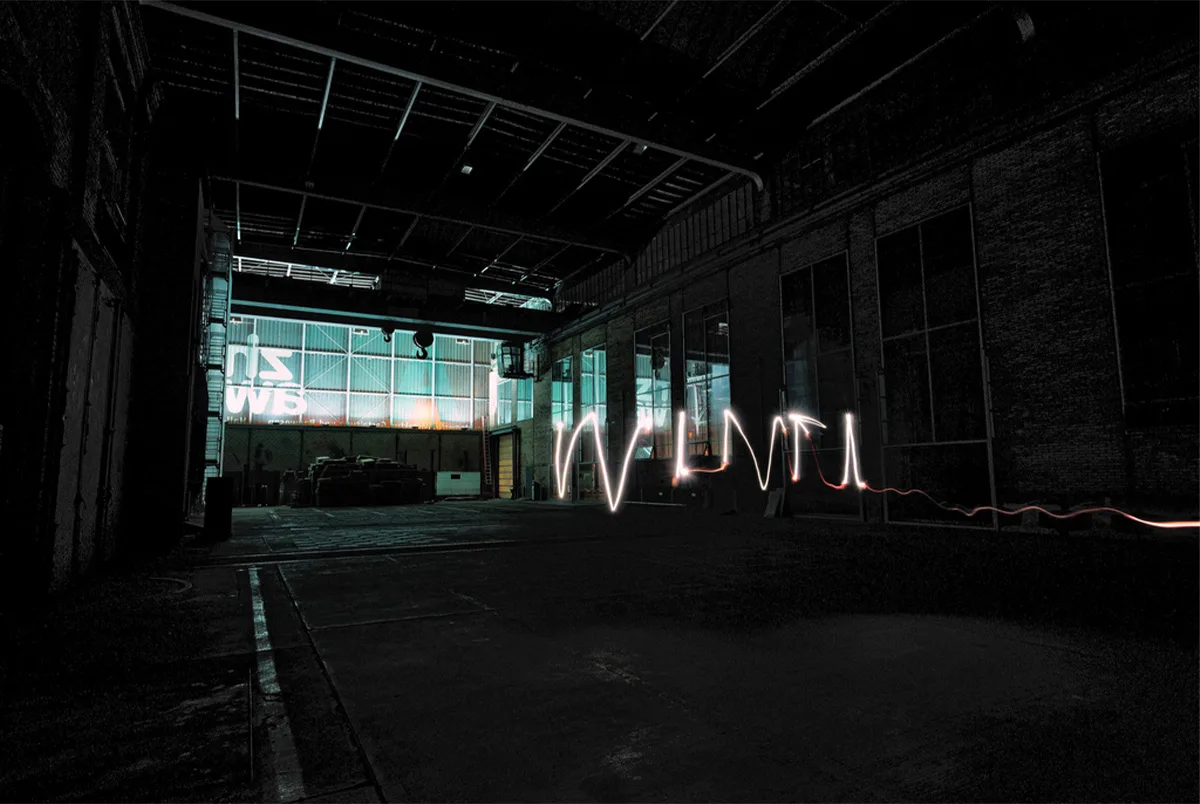

From ‘Uitoduro’ to ‘Winti’: how place names change

Since they were founded centuries ago, place name have undergone constant change. Unsophisticated descriptions of the local landscape, or ownership, have morphed into abbreviations popular among the young. In Winterthur’s case, it has gone from ‘Uitoduro’ to ‘Winti’.

Winterthur, the pasture gate

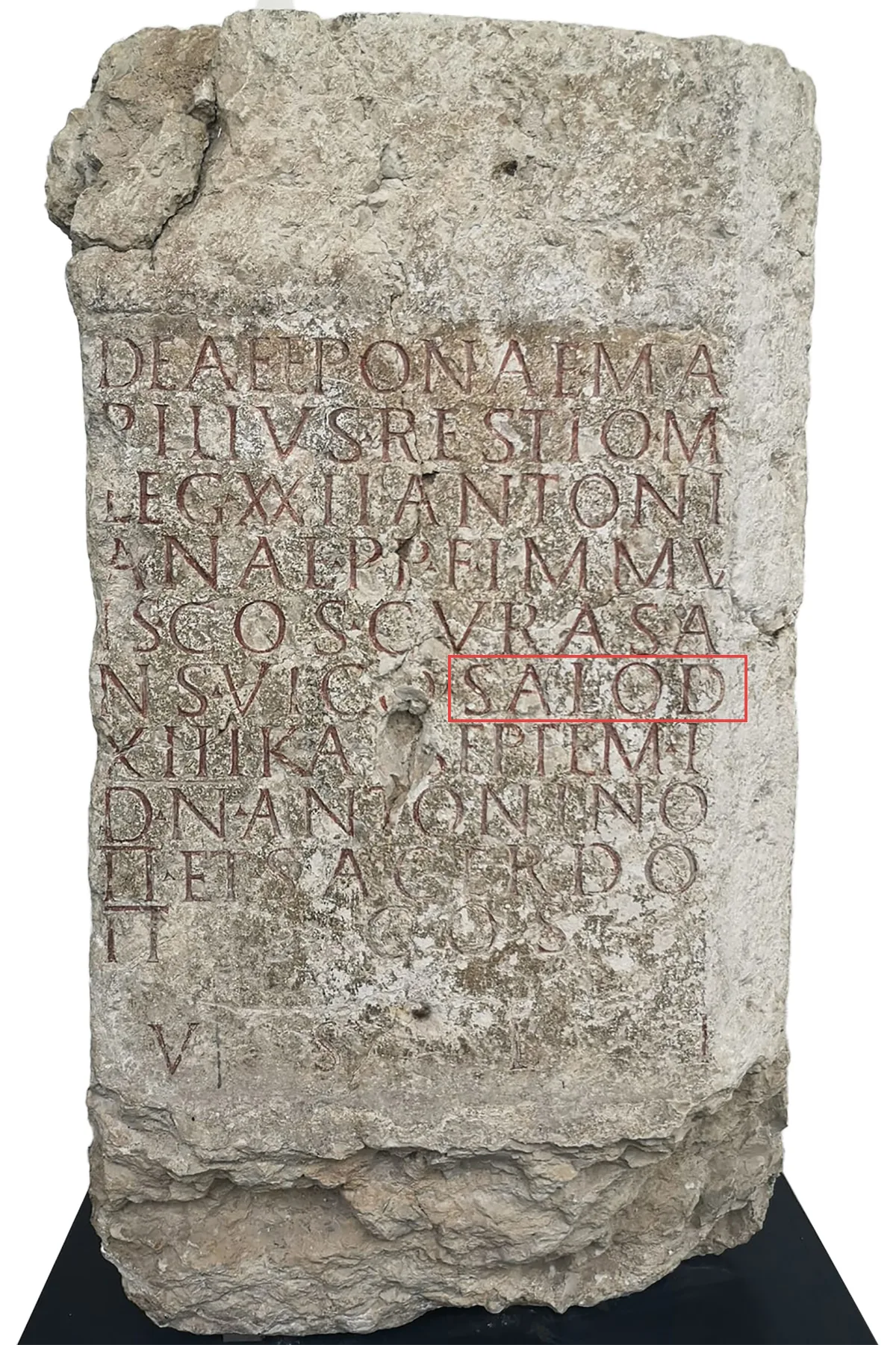

Celtic place names were Romanised

New Celtic-Roman establishments

Yet another change of language

What are the Winter and Thur in Winterthur?