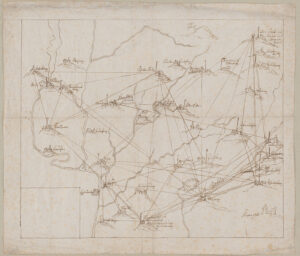

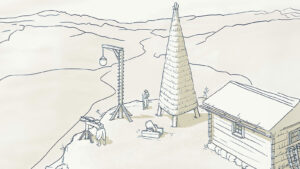

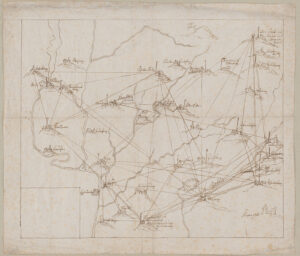

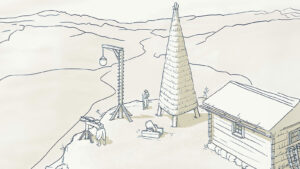

Watchtowers, the alarm system of the Old Swiss Confederacy

Whereas sirens sound the alarm nowadays, hundreds of years ago it used to be watchtowers. Beacons could mobilise troops within a few hours, from the Rhine to Lake Geneva.

Whereas sirens sound the alarm nowadays, hundreds of years ago it used to be watchtowers. Beacons could mobilise troops within a few hours, from the Rhine to Lake Geneva.