The Protestants of Locarno

It’s often forgotten that Locarno was a hotspot of confessional strife. The Locarnese Protestants and their subsequent expulsion in 1555 precipitated significant comment and a high degree of interconfessional distrust among the Swiss Confederates.

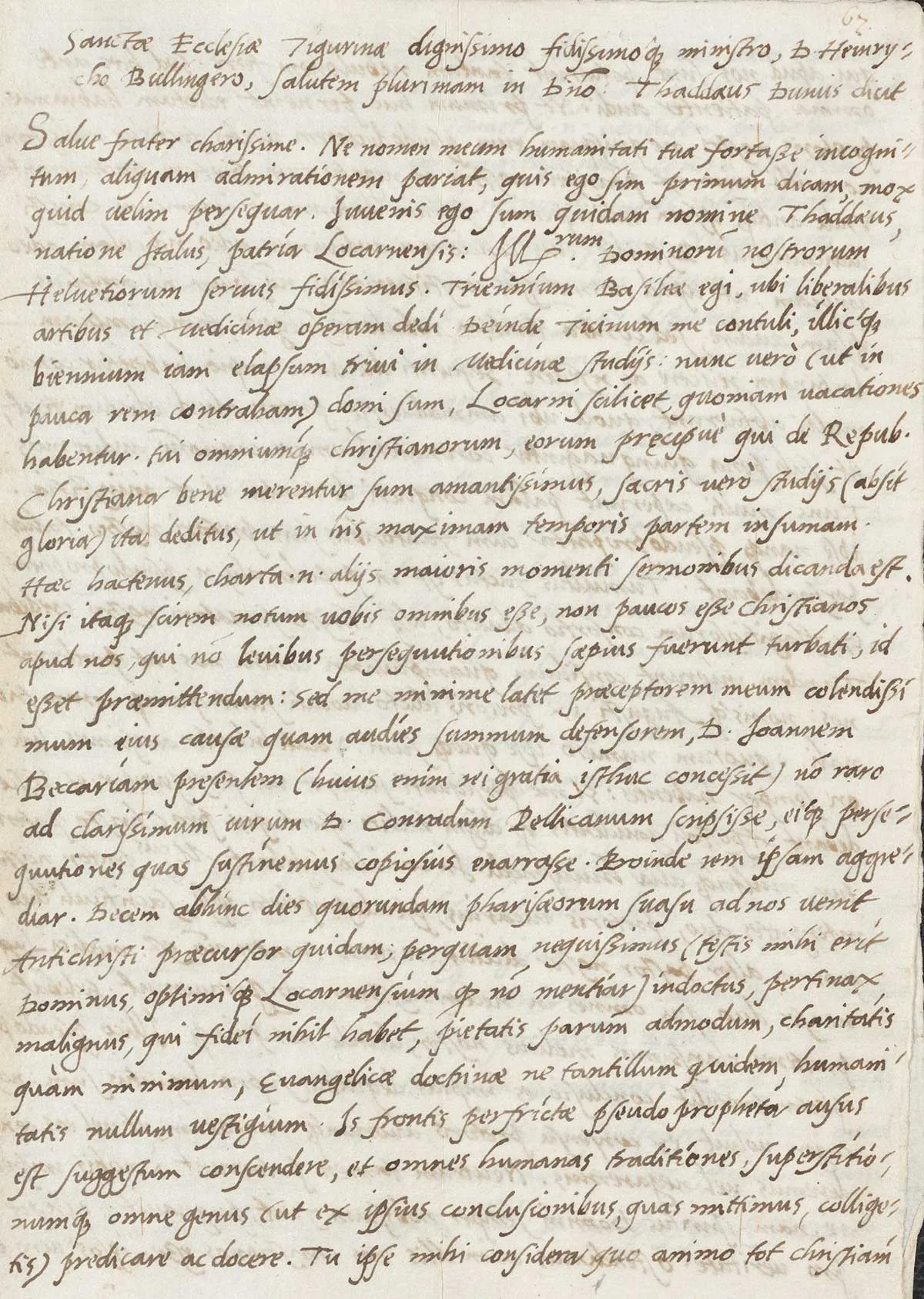

The number of believers is increasing day by day, even though the Antichrist does not cease through his false teachers to oppress those whom he knows to have pure and faithful opinions of Christ.

The church is God’s vineyard.

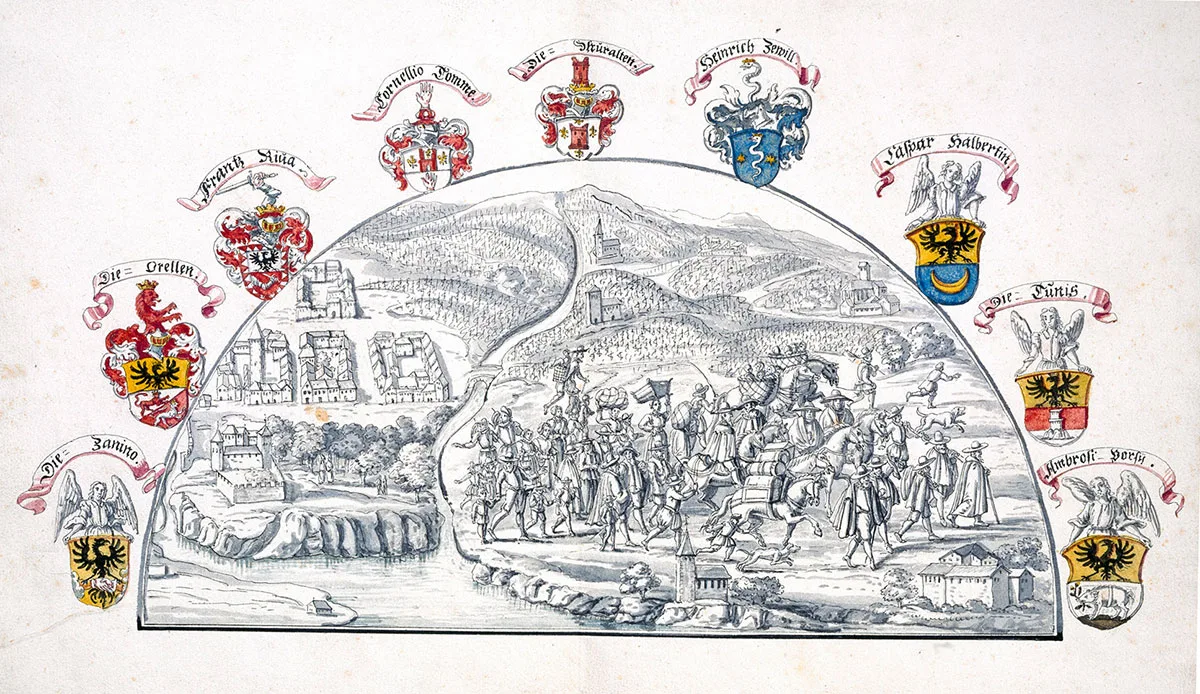

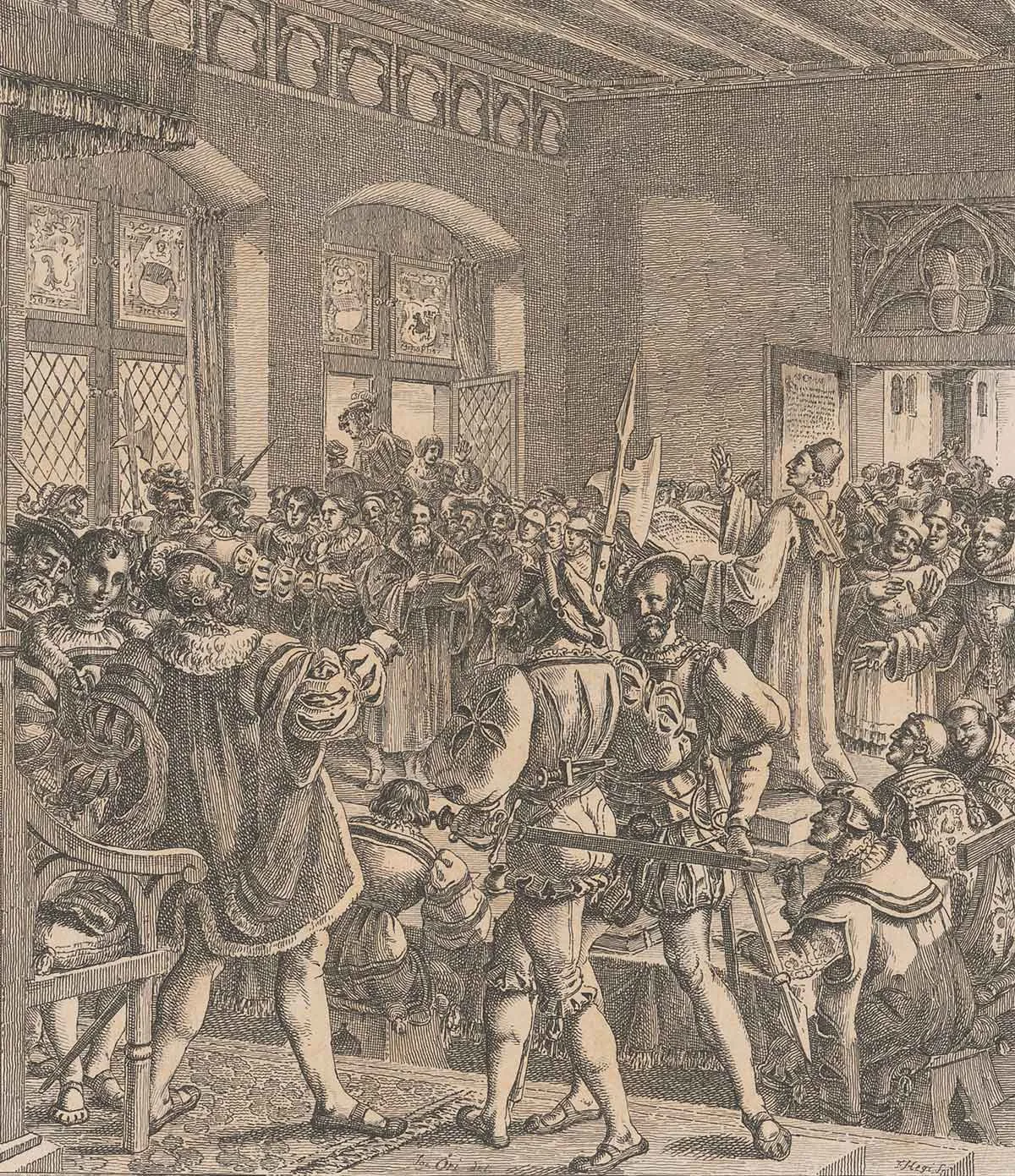

Panel paintings from the 17th century tell of the events leading up to the emigration of the Protestant families from Locarno to Zurich. Private archive of the von Orelli family / Photo: Archive of the von Muralt family in Zurich