Making money till the end

Kaspar Stockalper built up a conglomerate in Valais that shrewdly exploited the crises of the 17th century. To him, amassing wealth was a religious mission and a ticket to eternal salvation. But that didn't save him from a political conspiracy through which his rivals brought about his downfall.

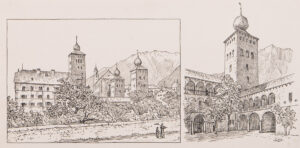

The King of Brig

In a three-part series, historian and author Helmut Stalder charts the rise and fall of Kaspar Stockalper, the “King of Brig”:

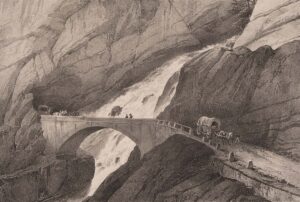

Part 1: The geopolitician from Brig

Part 2: Neutrality as a business model

Part 3: Making money till the end