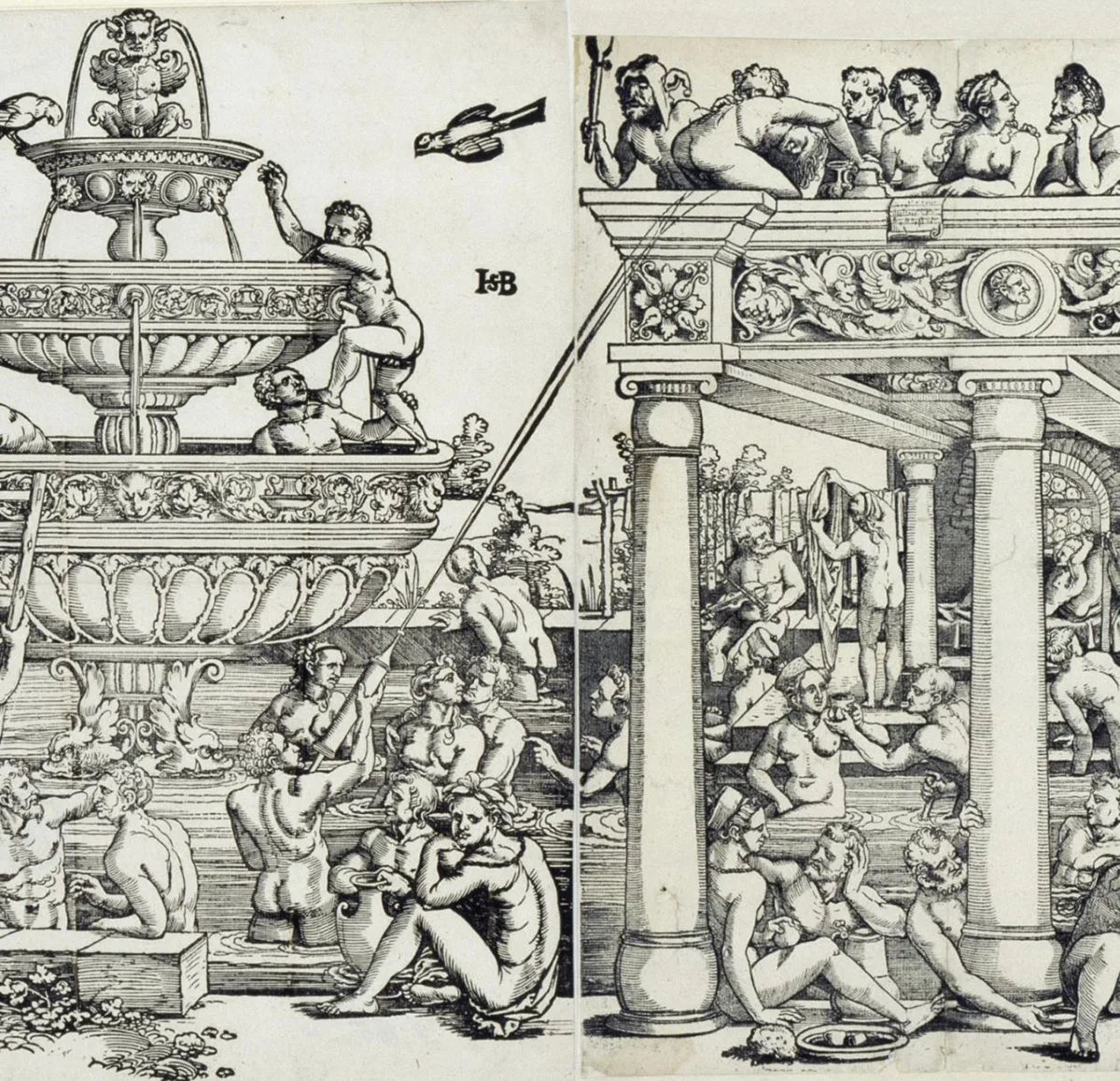

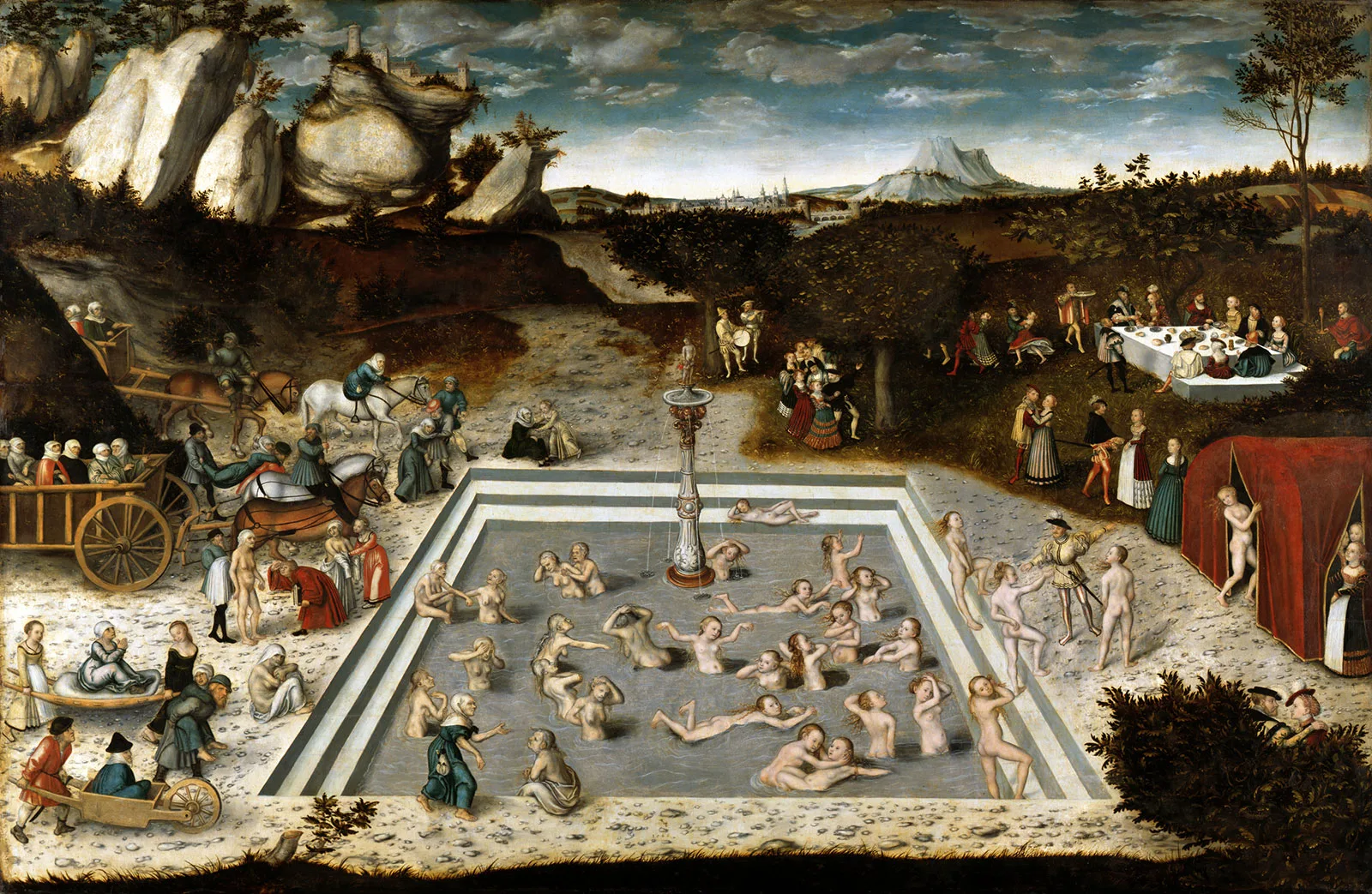

A scene of racy bathing pleasure as a social critique

The Reformation brought stricter social mores to many places in Europe, and artists had to adapt if they didn’t want to lose commissions. But these social mores were not popular with everyone – as revealed by this painting by Hans Bock in Basel’s Kunstmuseum.

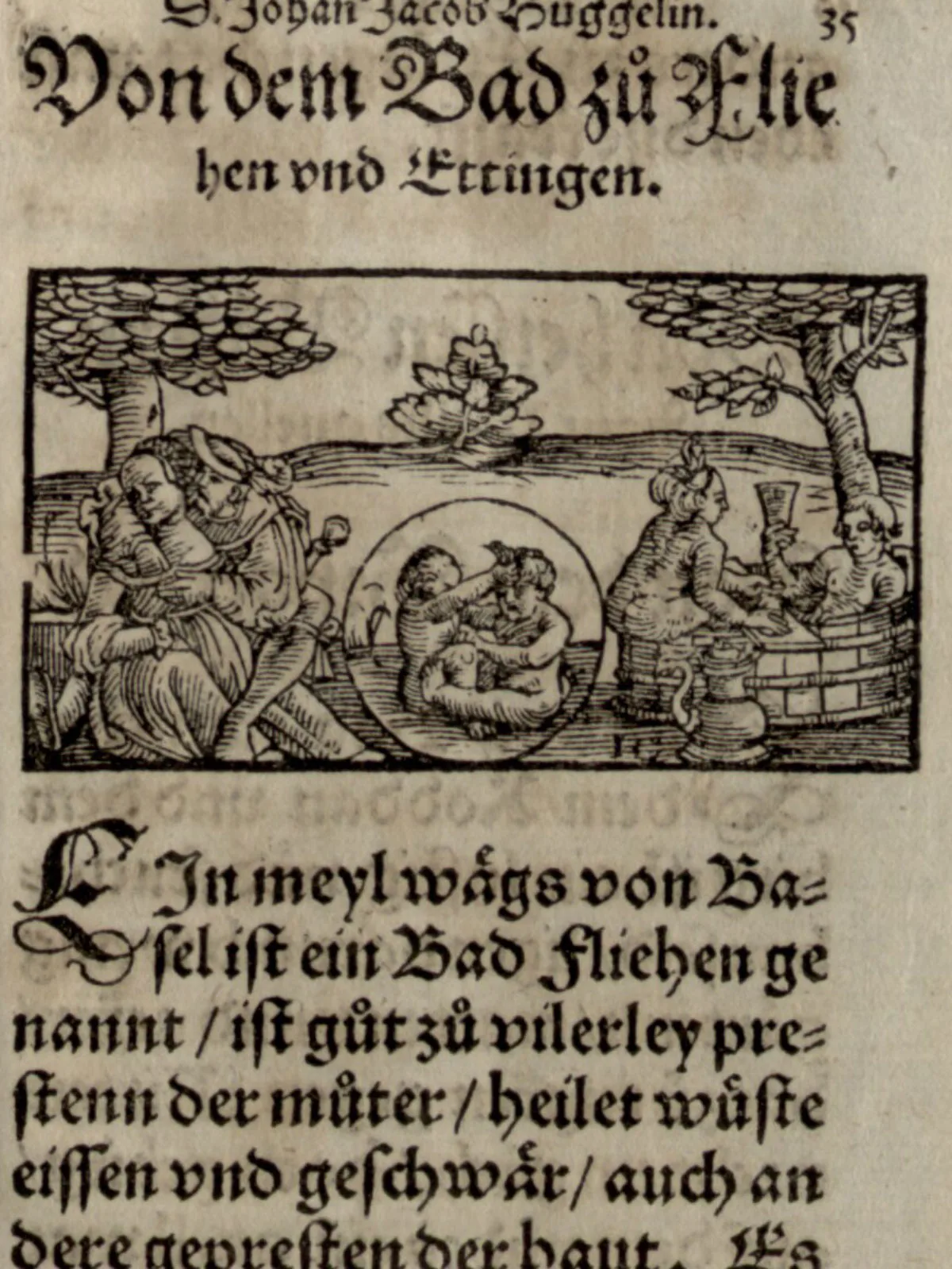

![Jakob Huggel’s ‘Von heilsamen Bädern des Teutsche[n]lands’ with its chaste cover...](https://blog.nationalmuseum.ch/app/uploads/huggel-titelbild.webp)