Direct democracy in the Free State of the Three Leagues

Direct democracy was already practised in the area that is now Graubünden over 500 years ago.

Pre-modern democracy in Graubünden

Common property (or Allmend) was ubiquitous and ensured that mountains, forests, waterways and meadows remained the property of the communes. Village mayors usually supervised the maintenance of this common property, relying on a set of village by-laws, which could be individually defined by each neighbourhood or commune. Parishes were also established on this cooperative basis, which is why from the 14th century we can talk of an evolution from church subjects to parishioners. This tendency to develop autonomous parishes soon led to a curbing of the bishop’s powers. Over time, the parishes, which were organised by neighbourhood, gained more of a say and were involved in the election of priests.

Noble territorial rule was quickly replaced by new social and political ruling classes, and the grouping of autonomous judicial communities led to the creation of early political entities. Over time, the communes and judicial communities formed a system of alliances that was characterised by strong decentralisation. In the 14th and 15th centuries, three Leagues thus emerged, which were based on shared values such as independence and democratic structures, and which were not genealogically defined. In many cases, the local nobility was not completely driven out, joining forces instead with the free peasants and citizens to form alliances.

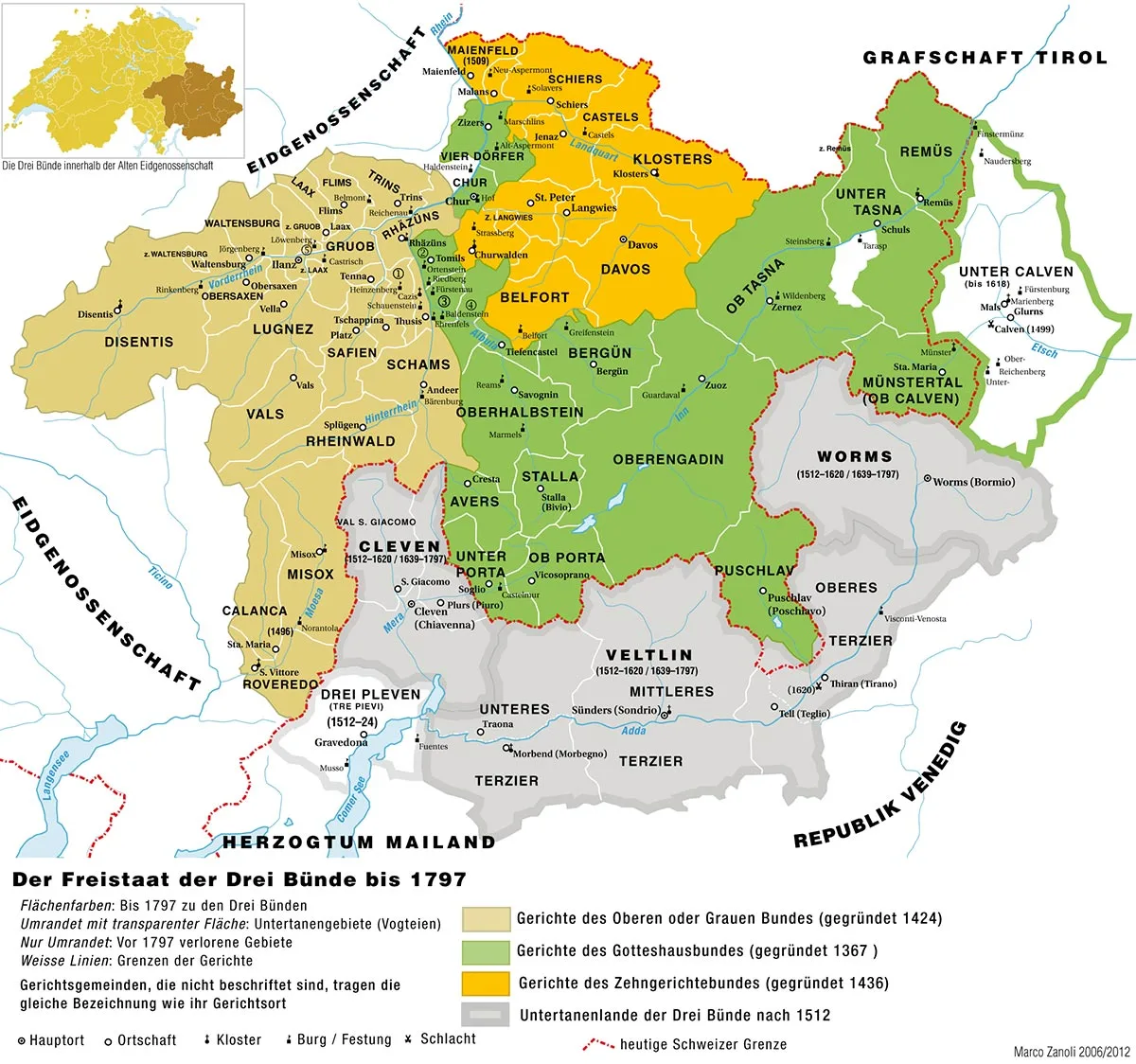

League of God’s House, Grey League, League of the Ten Jurisdictions

The League explicitly entailed the right for valley communities to have a say. These valley communities then emerged as ever clearer bearers of political power, increasingly undermining the power of the bishopric. The Upper or Grey League, formed in 1395 and re-organised in 1424, saw the abbot of Disentis, the baron of Rhäzüns and count of Sax-Misox join forces with the valley communes to safeguard peace, transport routes and therefore economic prosperity. The communes of the Grey League thus gained a significant say in decision-making over the three aforementioned senior figures.

The League of the Ten Jurisdictions, which was founded in 1436, was based on the alliance of ten judicial communities (i.e. communes that themselves are made up of several neighbourhoods/communes). The alliance brought together the Raetian territories belonging to the Toggenburg inheritance. The judicial communities pledged mutual assistance to better counter arbitrary treatment by the heirs.

To strengthen cohesion in the Free State, so-called Bundstage or community assemblies were introduced, which were similar to the Diet at federal level. From 1524 to 1797, the Free State was an associate member of the Confederacy and had a mercenary agreement with France. From 1512 to 1797, Valtellina and the counties of Chiavenna and Bormio also belonged to the Three Leagues as subject territories.

Judicial communities and assemblies – Free State rather than feudalism

The judicial communities themselves consisted of several neighbourhoods (vicinantia), which represented autonomous economic cooperatives and were often identical to parishes. The judicial communities generally convened as Landsgemeinde (cantonal assemblies). The sheer scale of the Free State prevented a common cantonal assembly for all three Leagues. The institution of the Landsgemeinde, which had existed since the 13th and 14th centuries in the original cantons of Zug, Glarus, and the two Appenzells, was taken as a model but adapted, although the principle was the same for the judicial communities: that a sovereign assembly of men eligible to vote would take part in all elections and make the important decisions. Legislation in the Free State was largely left to judicial communities. Every attempt to standardise civil and criminal law failed.

The loose alliance of the Free State as a whole had no joint authorities, no common judiciary and no joint treasury. Only war and peace, foreign policy, and the administration of subject territories were left to the Bundstag, the highest authority of the Free State. But the judicial communities always had a say on these matters through the referendum, so on the beginning and end of wars, on the drafting of men to patrol the borders, and on the number of troops to be mobilised. The judicial communities were also involved in the conclusion of treaties.

Important decisions relating to the Free State were made in Ilanz between 1524 and 1526. On 4 April 1524, a Bundstag for all three Leagues passed the First Ilanz Article, in other words the first state law passed by all three Leagues. This continued the political disempowerment of the secular and clerical feudal lords and bolstered democratic structures. This development was emphasised even more radically through the Second Ilanz Article of 1526.

The enactment of the First Ilanz Article led the Three Leagues to issue the first joint Constitution in the form of the Bundesbrief, or Federal Charter, at a Bundstag assembly in Ilanz on 23 September 1524 – 500 years ago. This year is the anniversary of that first Federal Charter. The purpose of the Federal Charter was to set out an oath that everyone had to swear by to preserve ‘peace, protection and order’ in the Free State. This also gave a significant boost to the process of internal cohesion and statehood as a sovereign, republican state. Through these radical interventions in the existing order, the Free State of the Three Leagues took on a form that endured until the Helvetic Republic of 1798 (and beyond that in a modified form until 1854).

The old referendum in Graubünden

Besides important fundamental matters of state, the referendums also dealt with trivial issues. But the central point was that the Free State’s foreign policy was in principle the responsibility of the entire state, and was therefore subject to the participation of the judicial communities. Internal affairs of state, such as general legislation, were usually dealt with by the judicial communities themselves within the framework of a Landsgemeinde (cantonal assembly), while the individual neighbourhoods conducted their business by means of community assemblies.

Impetus for Switzerland’s direct democracy

The canton of Graubünden’s history shows how the principles of modern democracy emerged. The Helvetic Republic made the Free State into the canton of Raetia from 1799 to 1803, and subsequently into an equal canton of the Confederation, and one which brought a great understanding of democracy.