The story of the Universal Postal Union

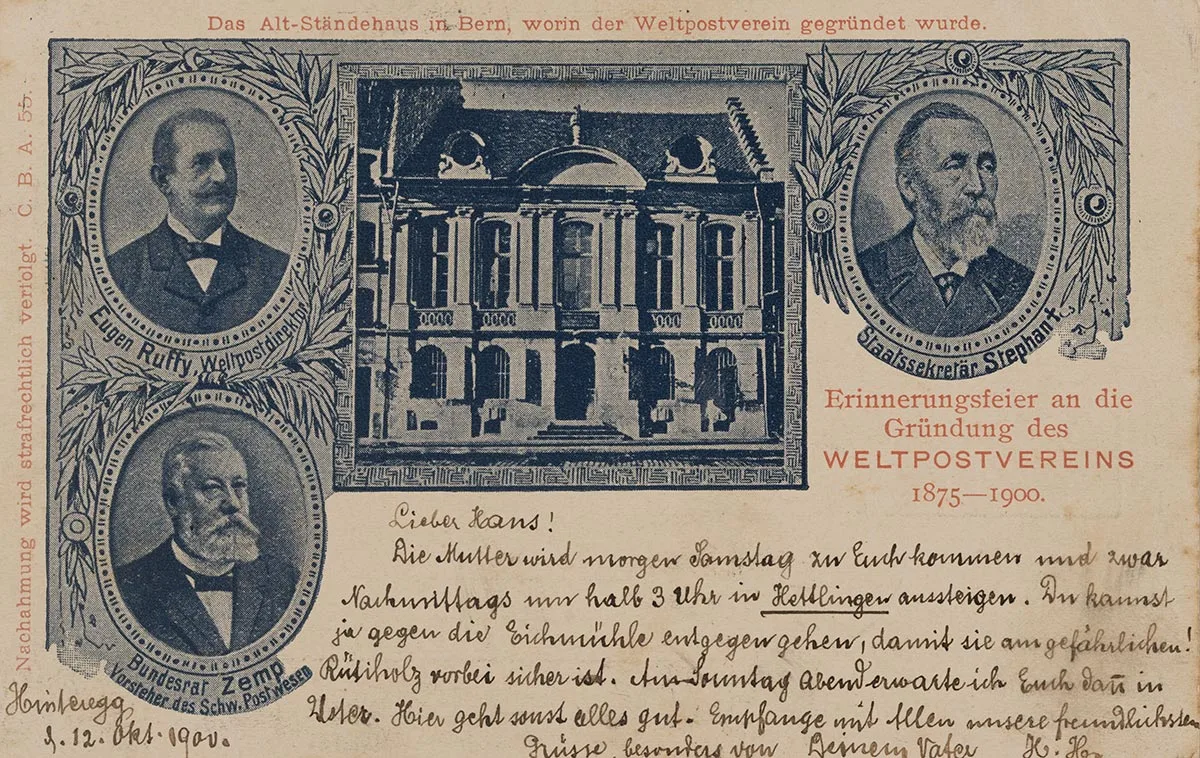

On 9 October 1874, the Universal Postal Union was established in Bern, laying the foundation for modern communication. To this day, it allows the global exchange of letters and parcels and is a cornerstone of global postal traffic.

The Universal Postal Union (UPU) is one of the key institutions of Switzerland’s foreign policy, as the country was entrusted with a growing number of new international organisations in the second half of the 19th century, pursuing a policy of multilateralism before the concept even existed. The UPU unified its member states into a single postal territory. The mutual recognition of charges and transit dues made it instantly possible for letters, postcards and parcels to be delivered across borders, and soon for money to be transferred, too – worldwide and with a steadily growing membership spanning all continents.

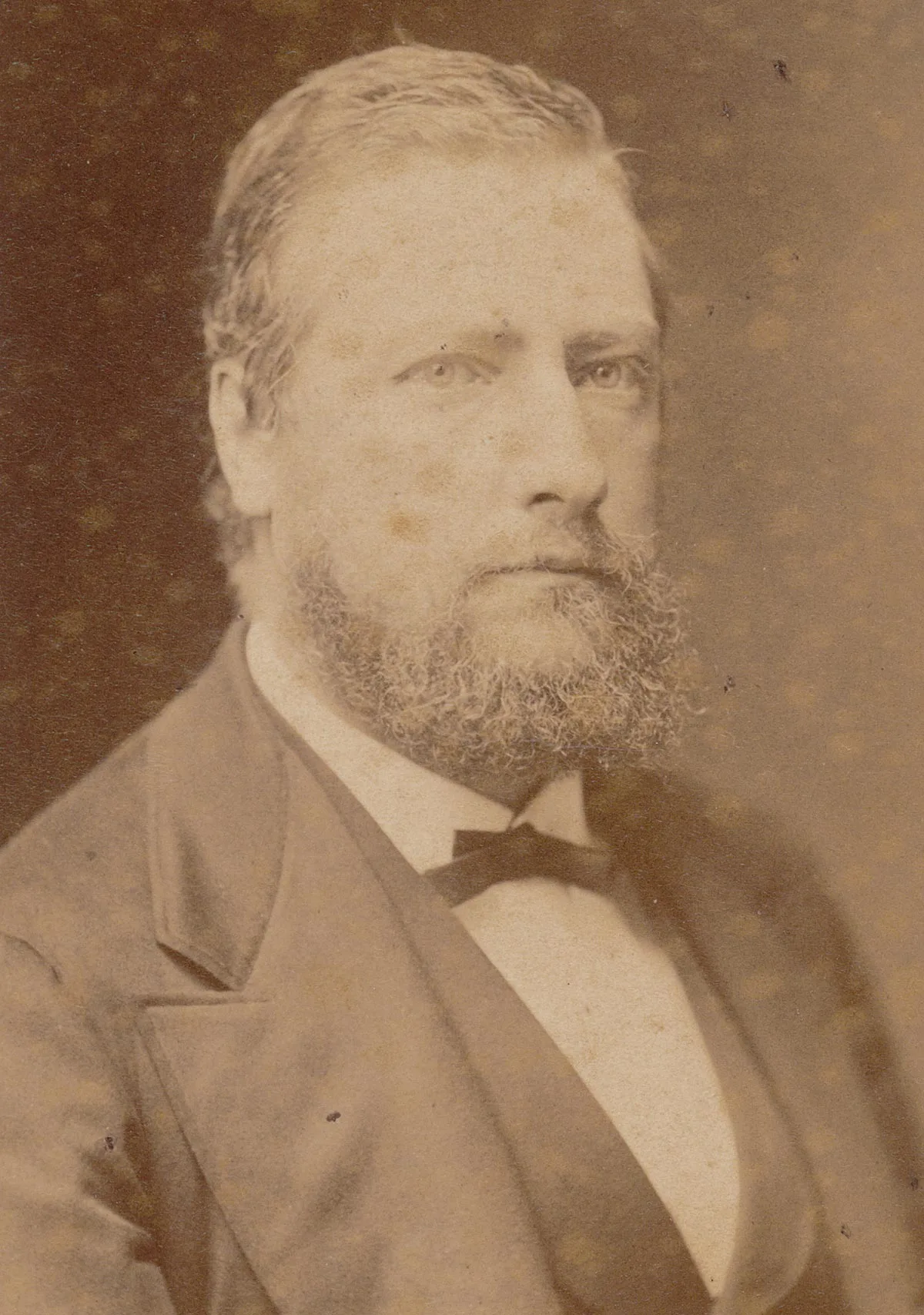

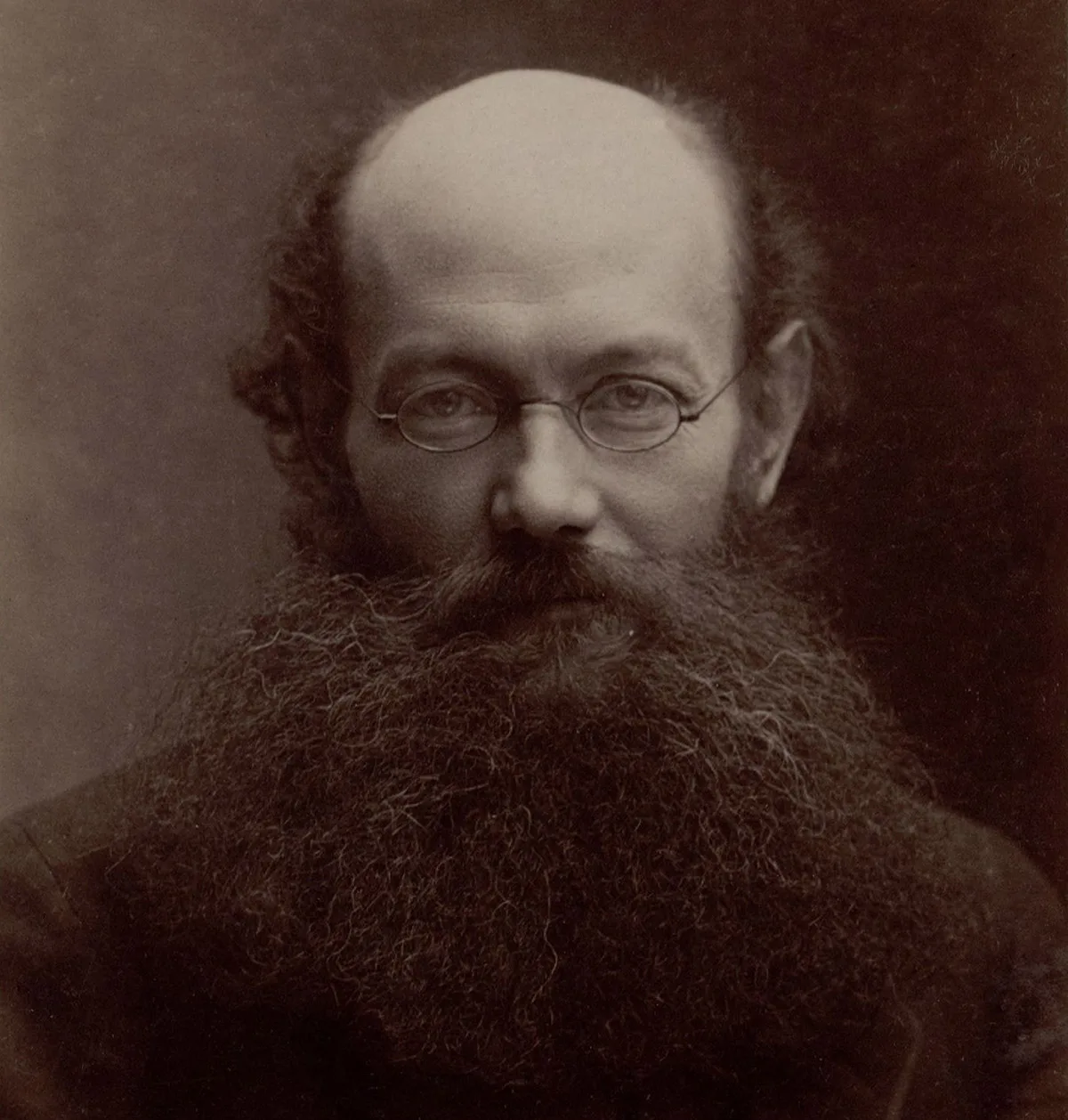

Even the founding congress went well beyond the customary diplomatic conferences of the ‘Concert of Europe’. The founding members who gathered in Bern hailed from no fewer than 22 countries, with representatives even travelling from the Ottoman Empire, Egypt and the United States. The Neuchâtel federal councillor Eugène Borel chaired the congress as head of the post department and was gifted a silver tea set at the last meeting by the conference participants as a thank you. The tea set attracted its fair share of press attention, and not only because of its hefty CHF 3,000 price tag. The attention was also due to the fact that the expectations of the new organisation were engraved on the silver platter, namely Libre échange postal (free movement of post) – Union générale des postes (general postal union) – Uniformité des taxes (uniformity of charges) and world peace no less through a Rapprochement des peuples (rapprochment of peoples).

Stephan is key to understanding the UPU and its significance in the history of international organisations. Evidently, the distribution of mail was not about state use of new technologies; the princely house of Thurn and Taxis had already made money from European mail transportation in the 16th century. For Stephan, it was about enforcing a state monopoly and in the case of Germany, this was done through sheer military might. Following the Austro-Prussian War, the Thurn and Taxis family were forced to give up the postal business and, when the German Reich was founded, a postal system was established for the new nation state.

This broad spectrum was reflected in the Universal Postal Union of the 19th century – but the organisation was not only demanded by a very wide range of different actors. It also had an almost unavoidable influence on people’s lives, whether because they had started writing letters, or witnessed the explosive expansion of post offices in their local areas, or as merchants who had benefited from the establishment of parcel post and free postage for sample shipments. The UPU internationalised and globalised the postal system as a state monopoly. This key feature has become increasingly problematic in the 21st century, as private online and courier services now call into question the model and challenge the Universal Postal Union, which has been a UN specialised agency since 1948.

An international organisation for millions of people

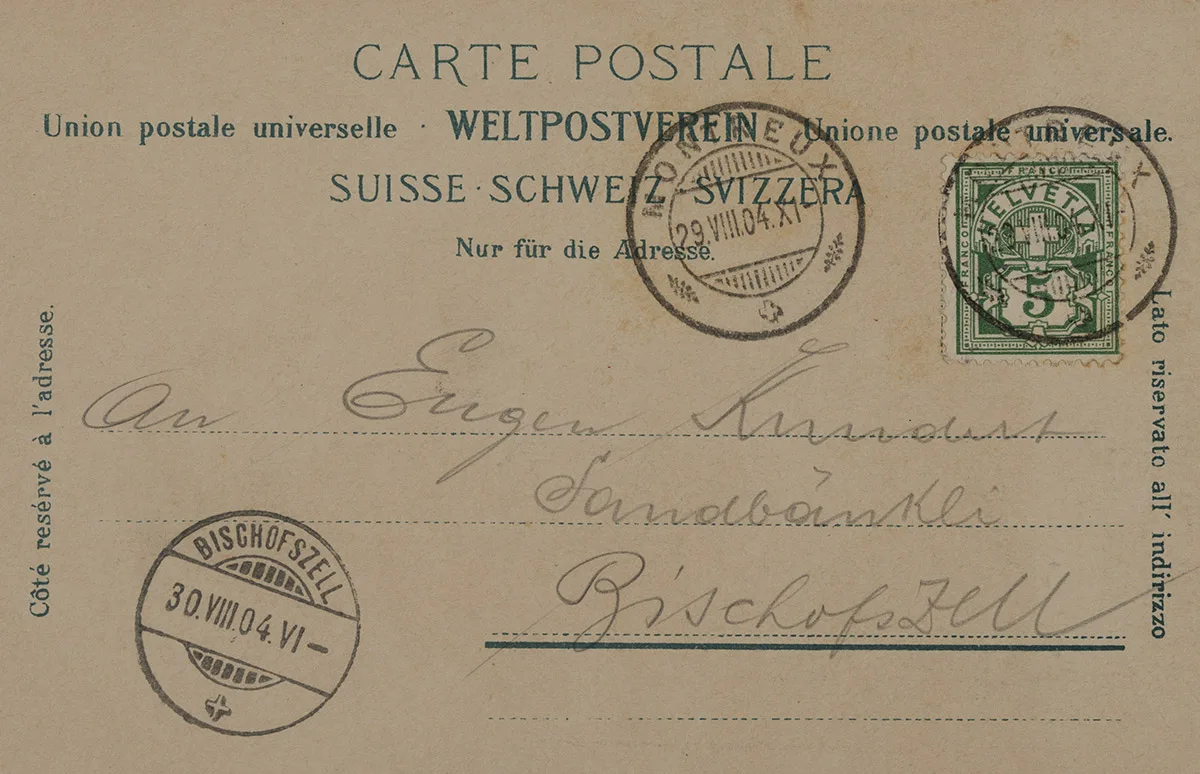

At the conference in Paris, diplomat and Swiss delegate Johann Konrad Kern highlighted the vast scale of the Universal Postal Union, which had grown to 38 member states, and covered a population of 652 million people. He wanted to show that the organisation was continually growing, and therefore shaping people’s everyday lives. The global machinery of the UPU allowed millions of migrants to exchange letters with their families at home. People made use of the new medium of postcards that bore the logo of the Universal Postal Union. The postage stamps recognised by the UPU, which actually were only meant to regulate the transfer charges, became visual carriers of national identity and collectors’ items for philatelists the world over.

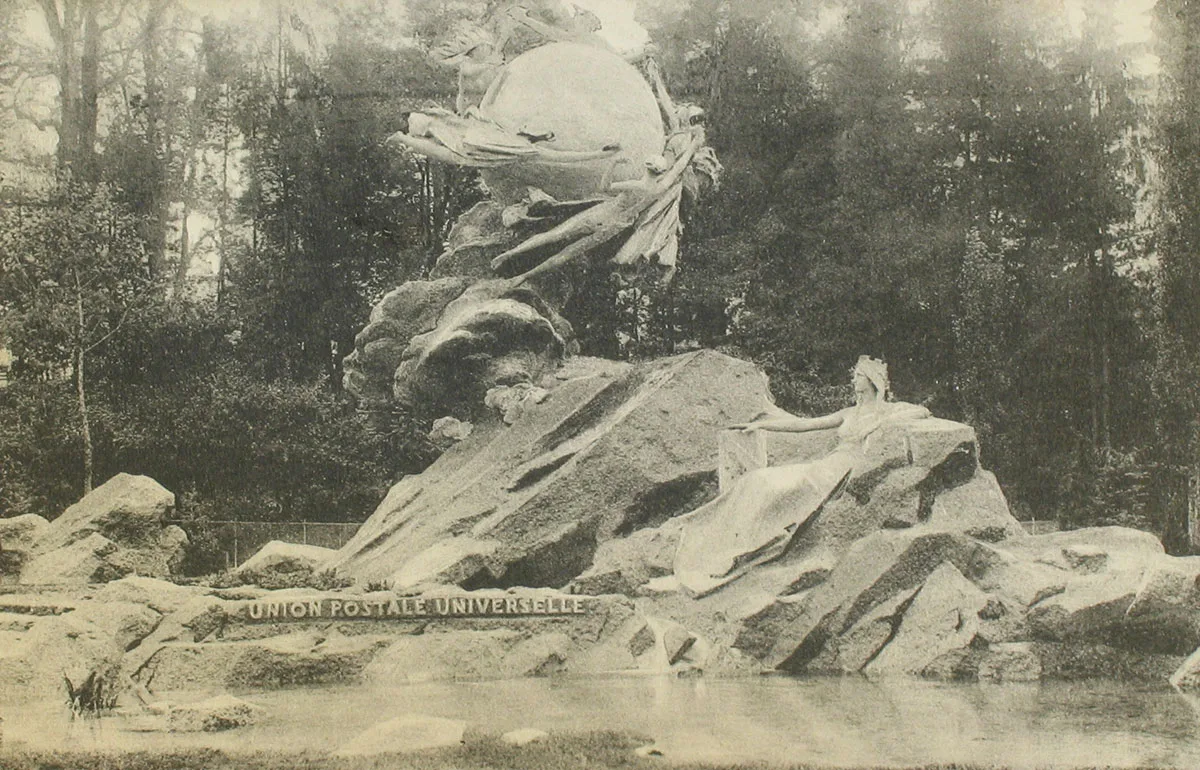

The monument, which was displayed in close proximity to the Federal Palace, was not a hit with everyone. But it provided the UPU with a recognisable symbol that became a part of Swiss cultural heritage before the First World War and is still used to this day. The cosmopolitan chocolatier and pacifist Theodor Tobler distributed poster stamps in the artificial language Ido with his company’s products, one of which featured the motif of the Universal Postal Union monument – but instead of letters, the continents were slipping each other milk chocolate bars.

Fragile freight for bee keepers

Postal accounts for women and discounts for ruling princes

Besides such everyday examples, the membership of the Universal Postal Union, the rapid integration of the colonies, and the long-delayed admission of China also reflect the global power dynamics at the time. The late recognition of China as a member of the Universal Postal Union is a telling example of how the West and Japan covered the Chinese territory with post offices, thereby not only enjoying economic advantages but also asserting claims to political power primarily in the East Asian trading metropolises and the major ports.

Collaboration

This text was born of a collaboration between the Swiss National Museum and the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland research centre (Dodis). Madeleine Herren is Chair of the Dodis Commission and co-editor of the source edition Die Schweiz und die Konstruktion des Multilateralismus (‘Switzerland and the construction of multilateralism’) volume 1, published in 2023.