How Swiss period rooms influenced American museums

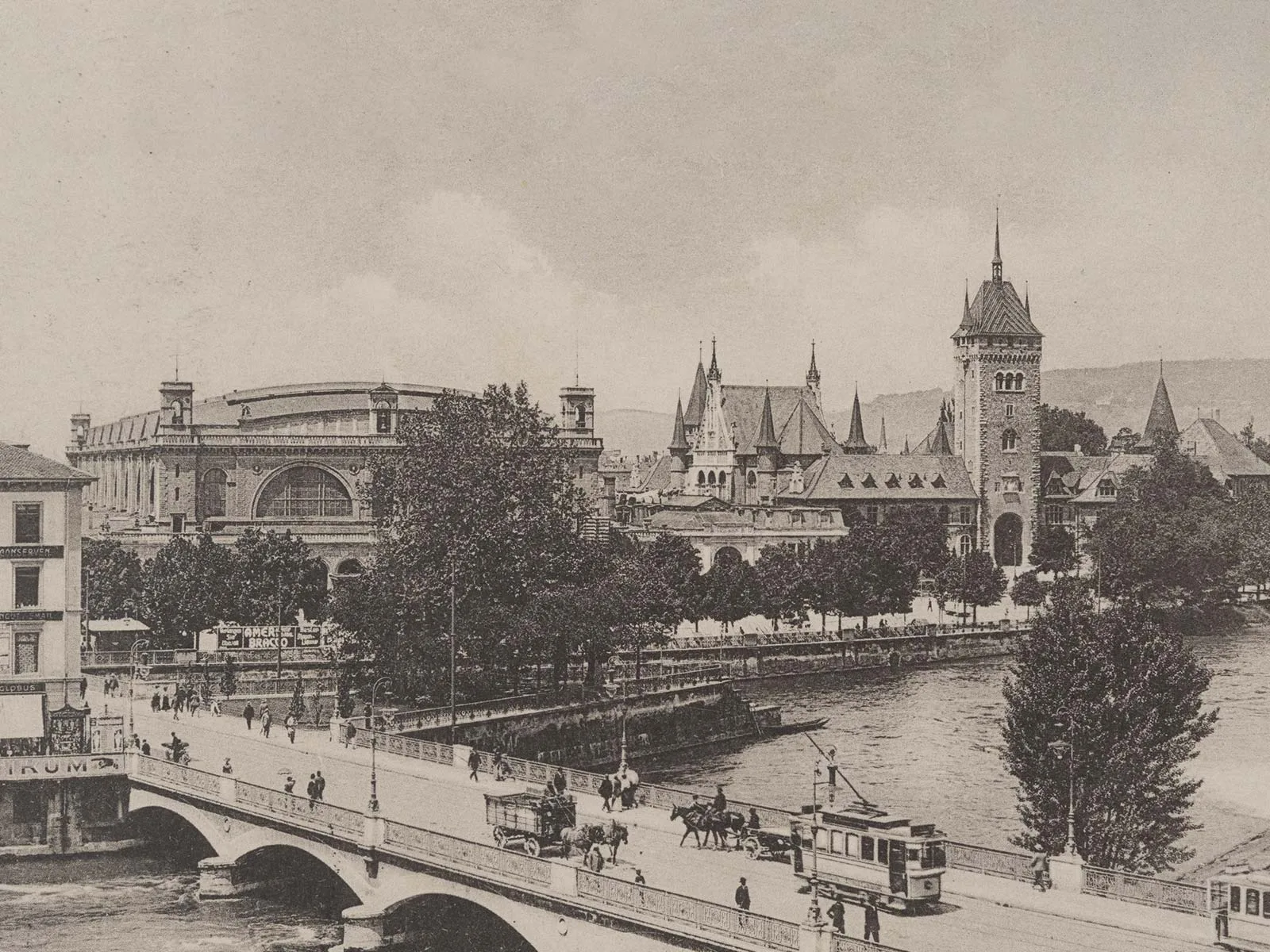

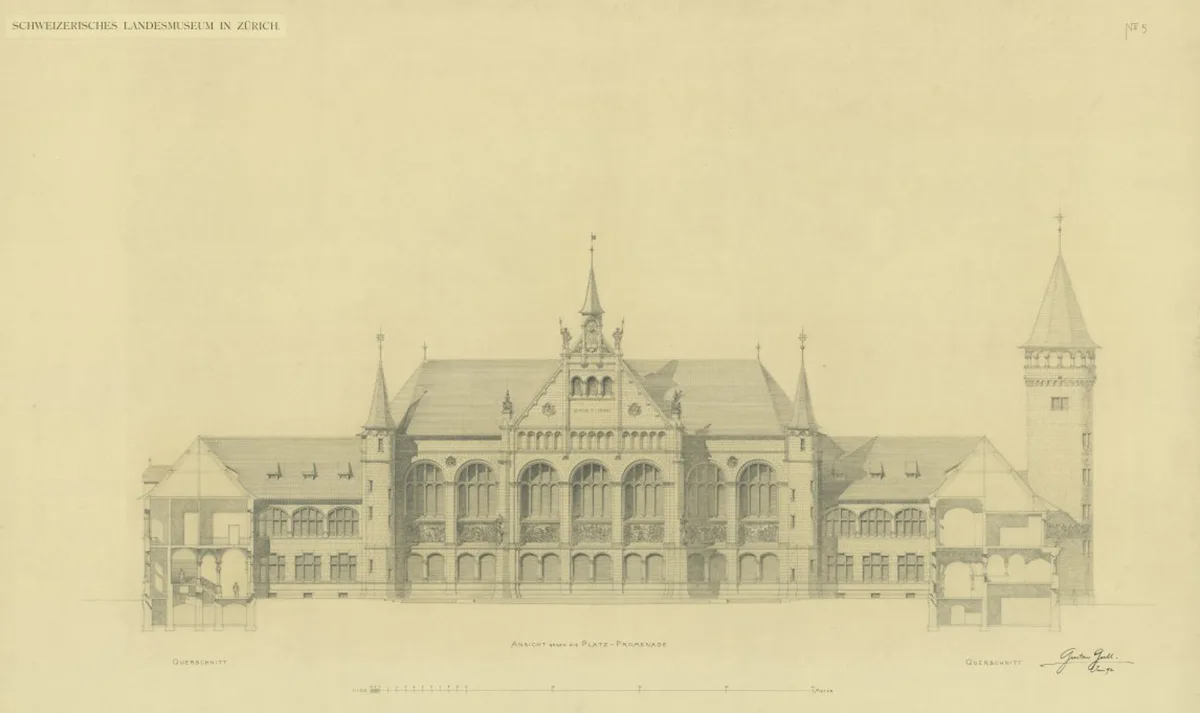

After it opened in 1898, the Swiss National Museum in Zurich and its period rooms served as an important model for museums in the United States.

A new view of history to attract more visitors

The collection

The exhibition showcases more than 7,000 exhibits from the Museum’s own collection, highlighting Swiss artistry and craftsmanship over a period of about 1,000 years. The exhibition spaces themselves are important witnesses to contemporary history, and tie in with the objects displayed to create a historically dense atmosphere that allows visitors to immerse themselves deeply in the past.