Maps and Switzerland’s linguistic destiny

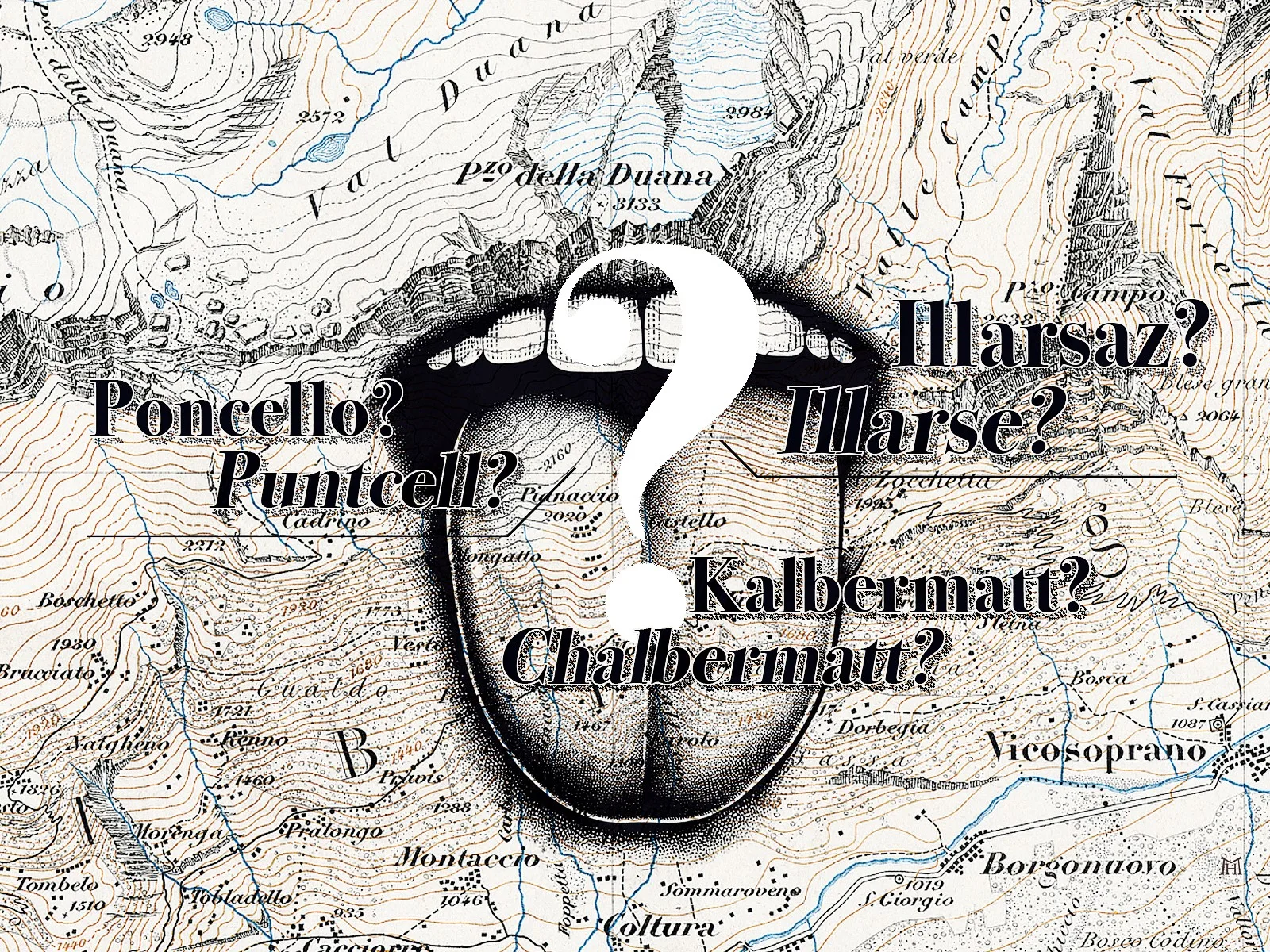

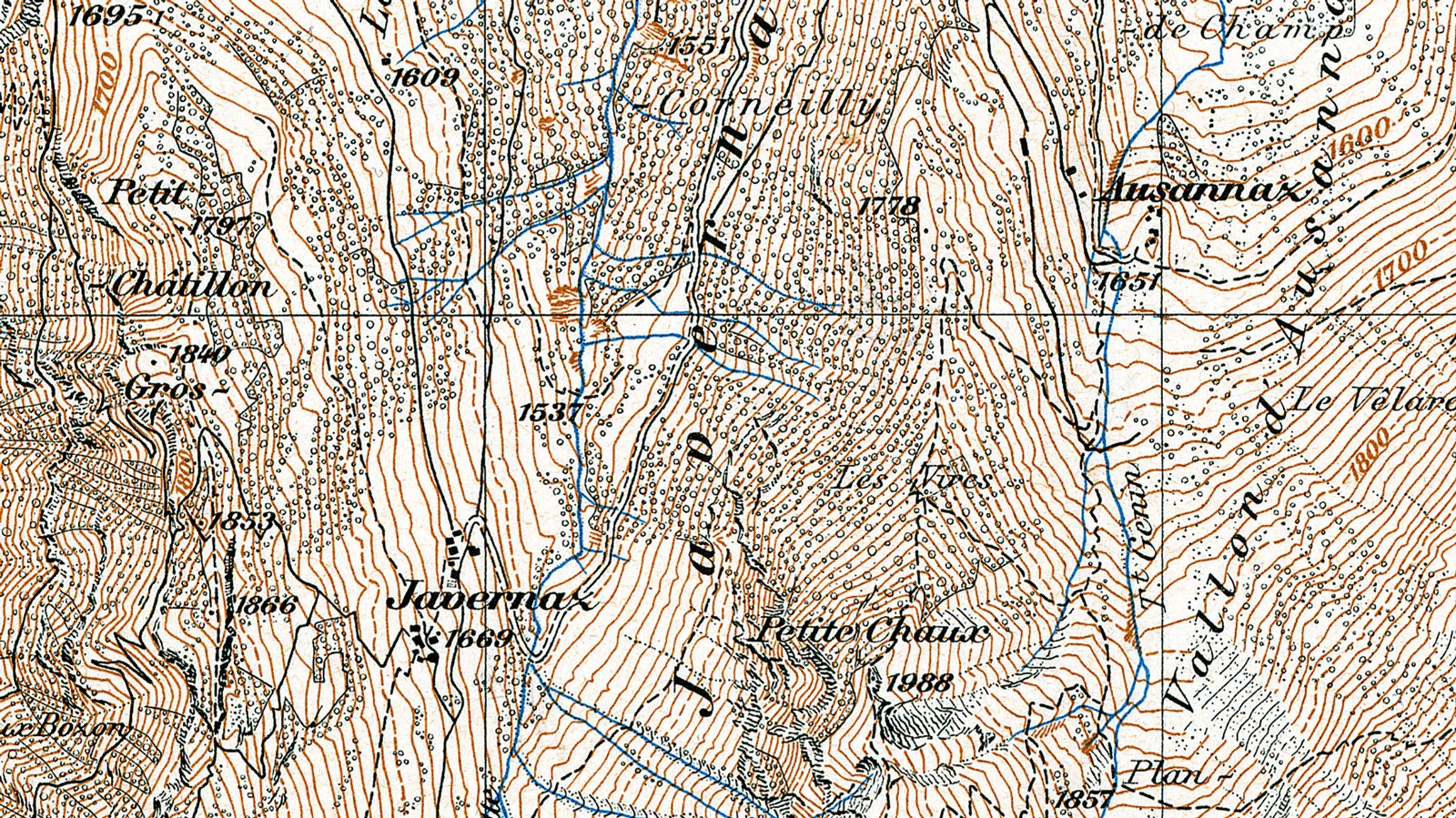

Poncello or Puntcell? Illarsaz or Illarse? Kalbermatt or Chalbermatt? The spelling of place names has frequently been a contentious issue in all parts of Switzerland, particularly when it comes to striking the right balance between standard language and dialect.

swisstopo historic podcast (in German)

Are you interested in the history of place names? You can find out more in the swisstopo historic podcast. Take a listen – available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or here.

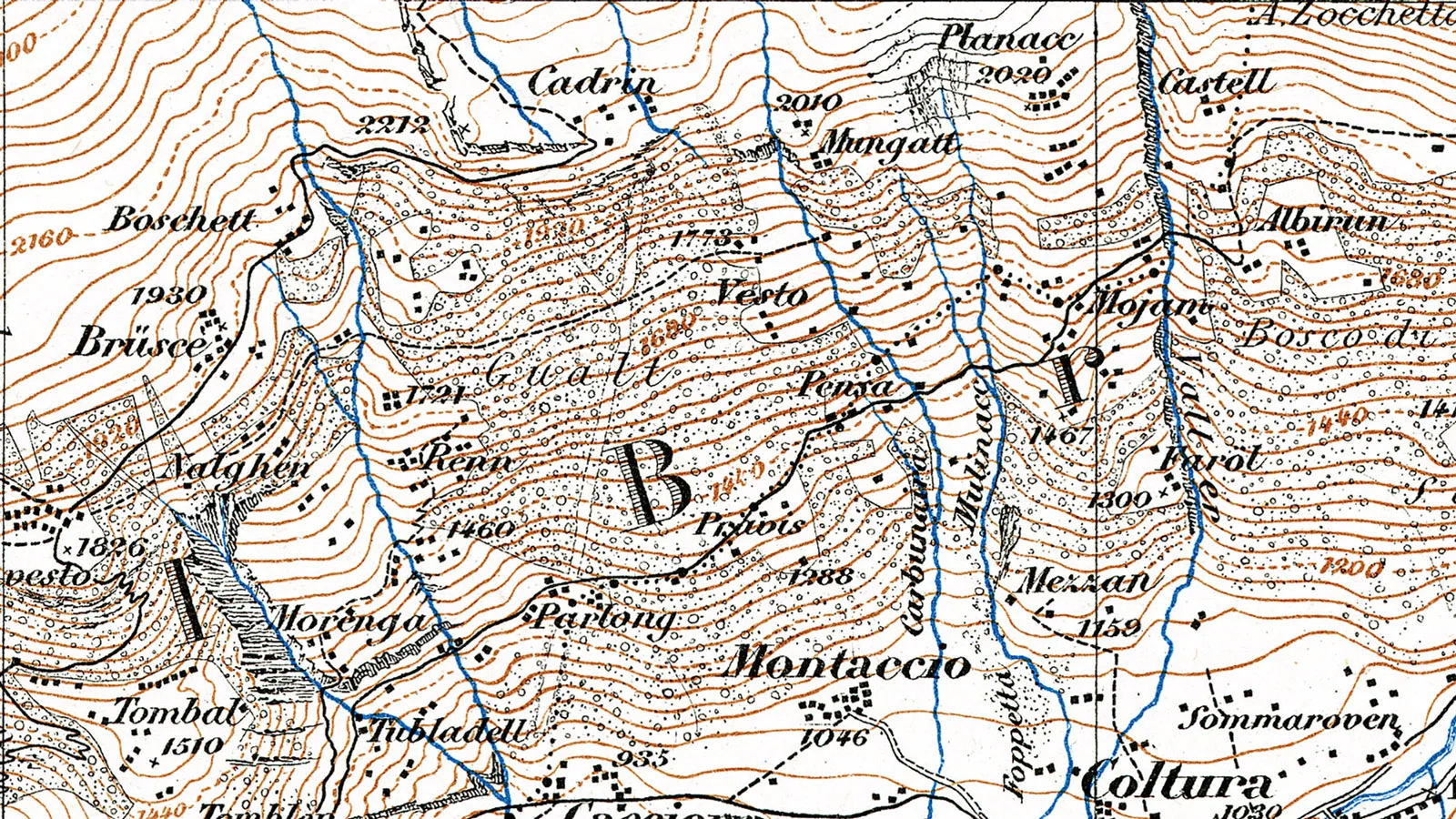

Bargaiot and Italian

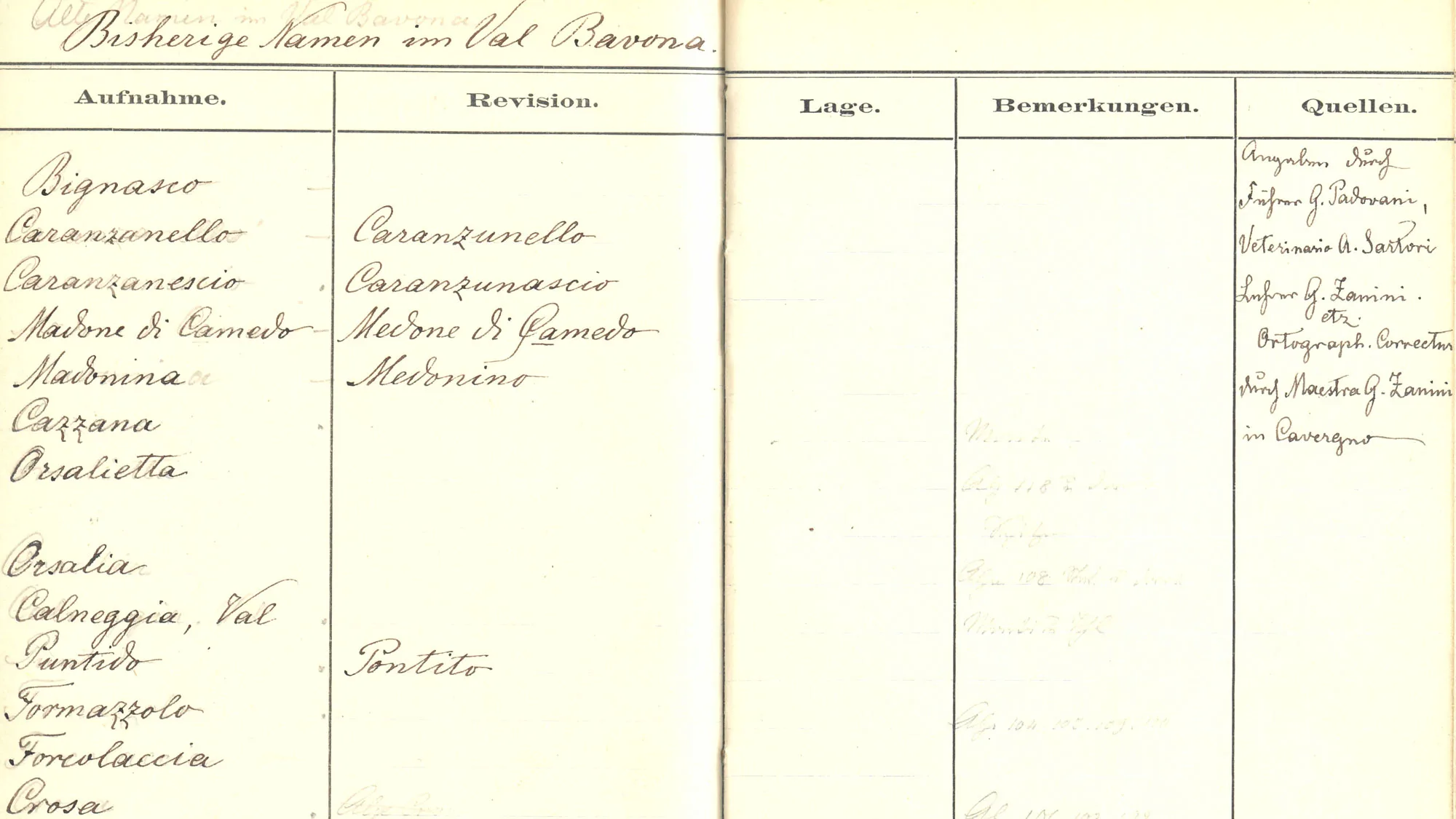

We don’t know exactly what made the cartographers radically alter the place names. But the systematic Italianisation was probably intended to ensure linguistic standardisation. In doing this, the cartographers had broken the inviolable rule whereby names should be recorded using local spellings. But this was the only way of ensuring that cartographers could engage with local populations about map content.

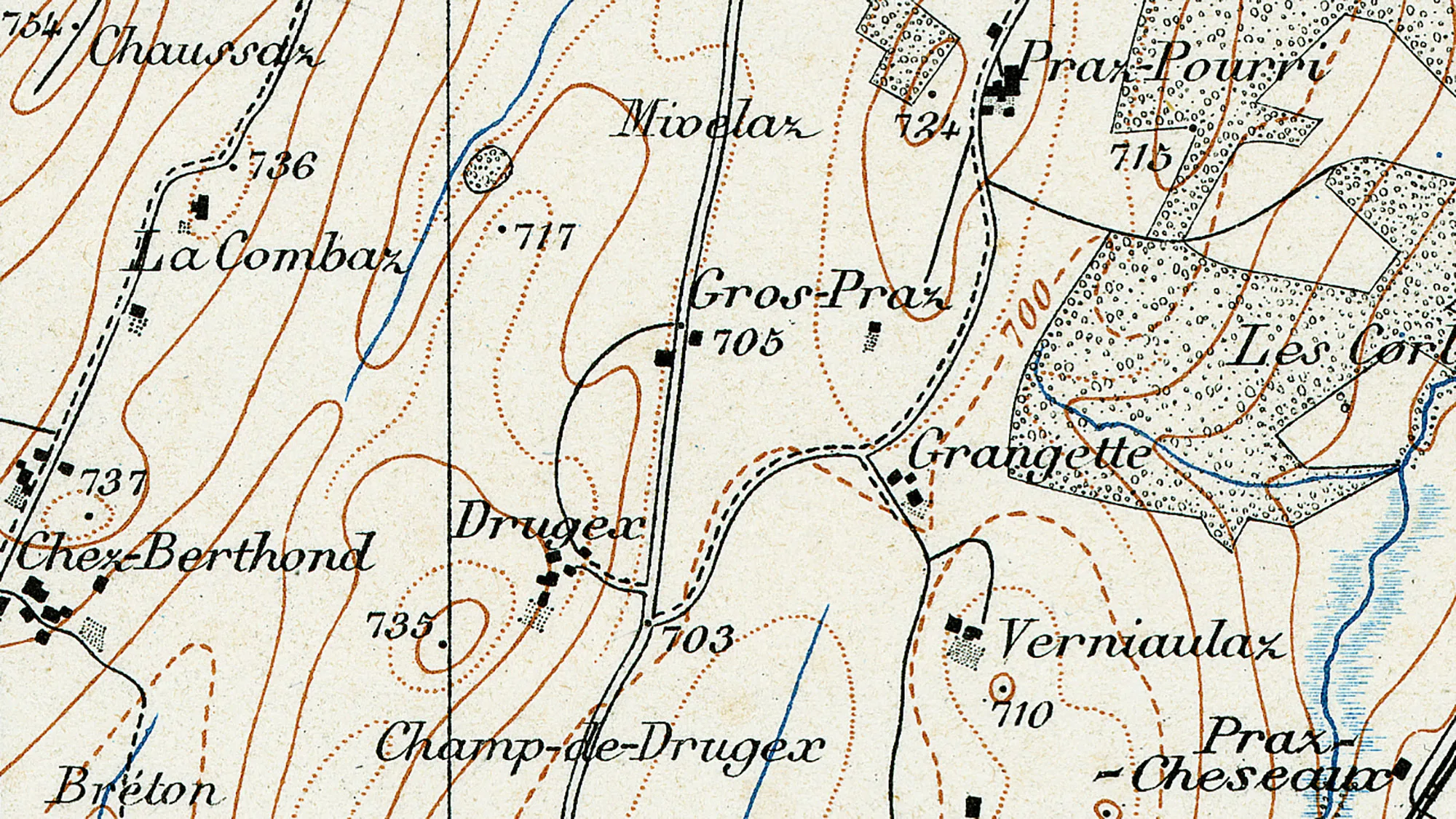

Patois and standard French

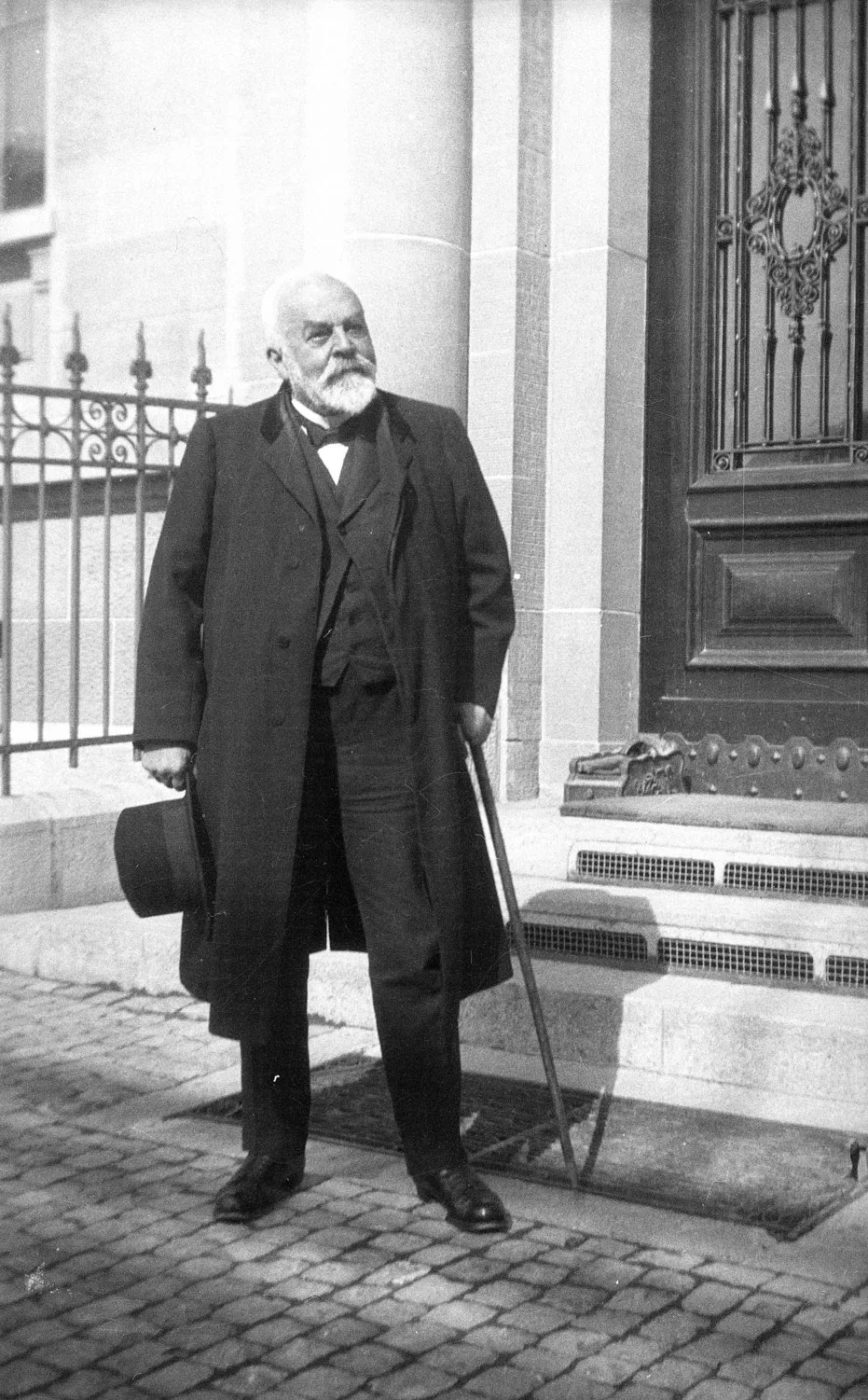

In 1910, Rossel went to the Federal Council and called for a systematic ‘Frenchification’ of geographical names in Romandy. He cited his fellow campaigner, professor of philology Ernest Muret from Geneva:

It is crucially important that dialect place names adopted on maps and in official use are frenchified in moderation, with tact and discretion, but in a generalised and systematic way […]

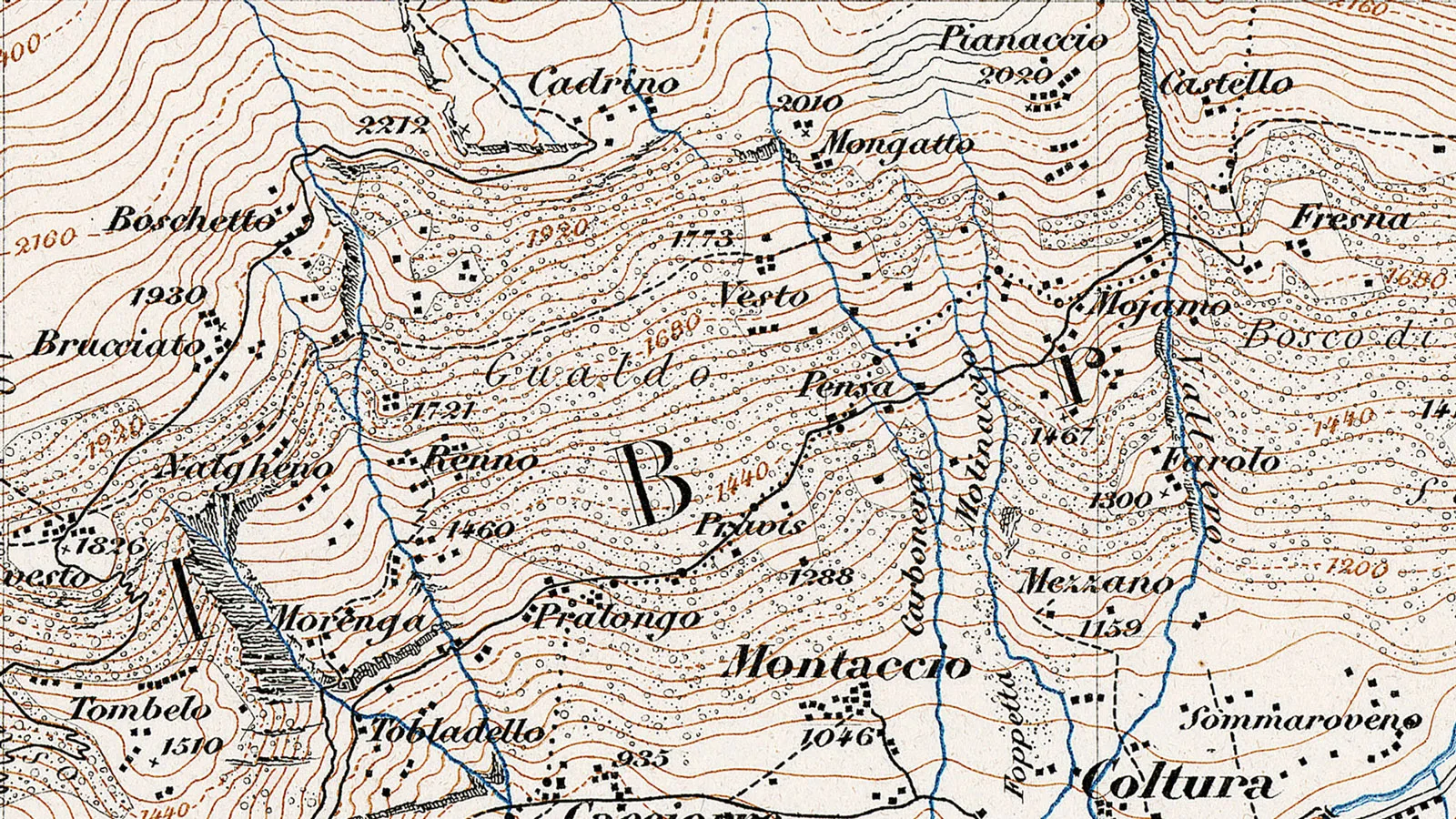

Despite this clear rejection, the proponents of Frenchification successfully realised their proposal for a short time on maps of the Lower Valais. This was down to topographer Charles Jacot-Guillarmod. As a high-ranking staff member at the Federal Office of Topography, he shared Virgile Rossel’s view and decided to make it a reality: in 1908, Jacot-Guillarmod surreptitiously frenchified a number of geographical names on sheet 484 of the Siegfried Map ‘Lavey-Morcles’. Partly because of this unauthorised intervention, the engineer was removed from his position as head of the topography division in 1912.

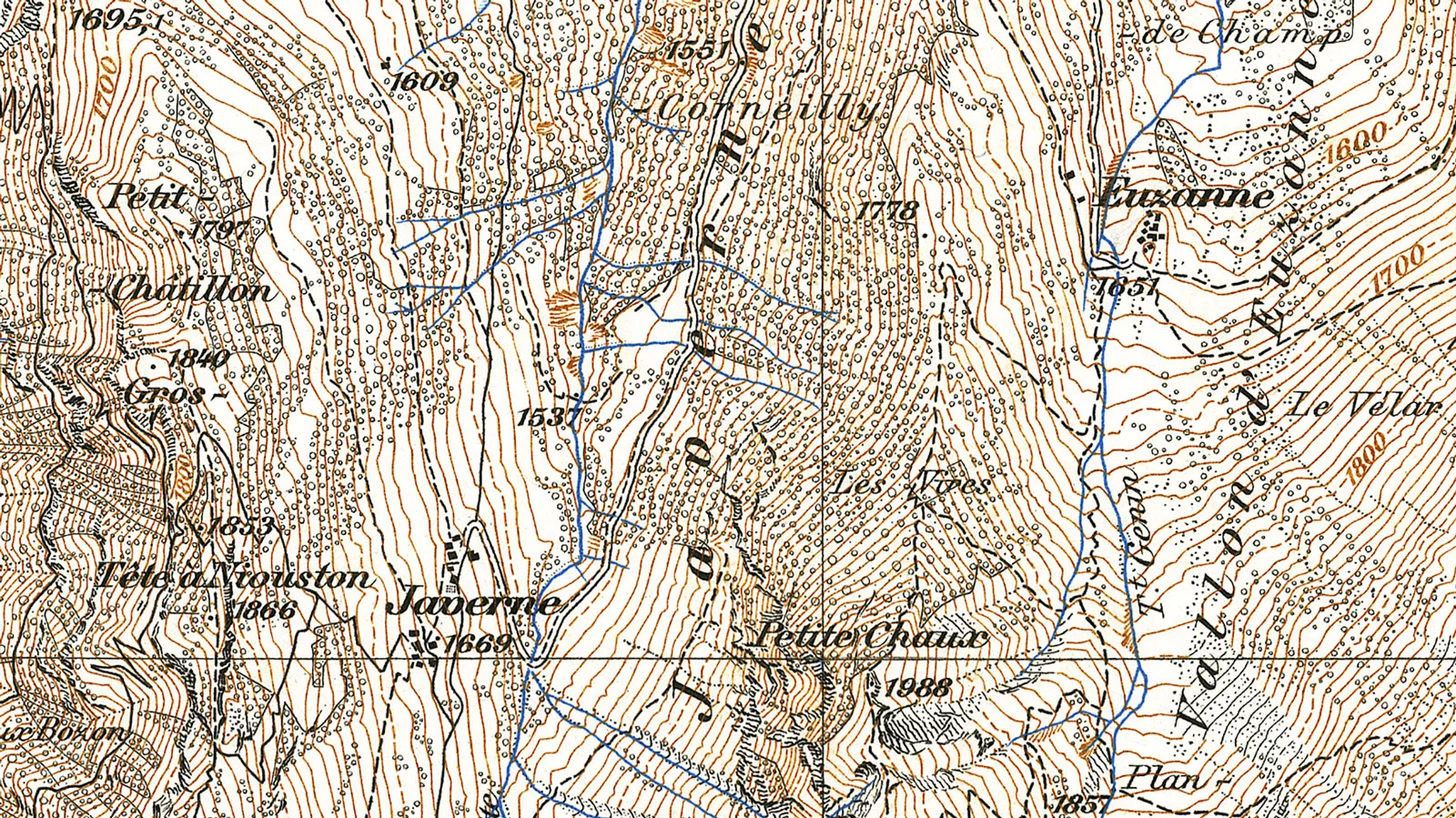

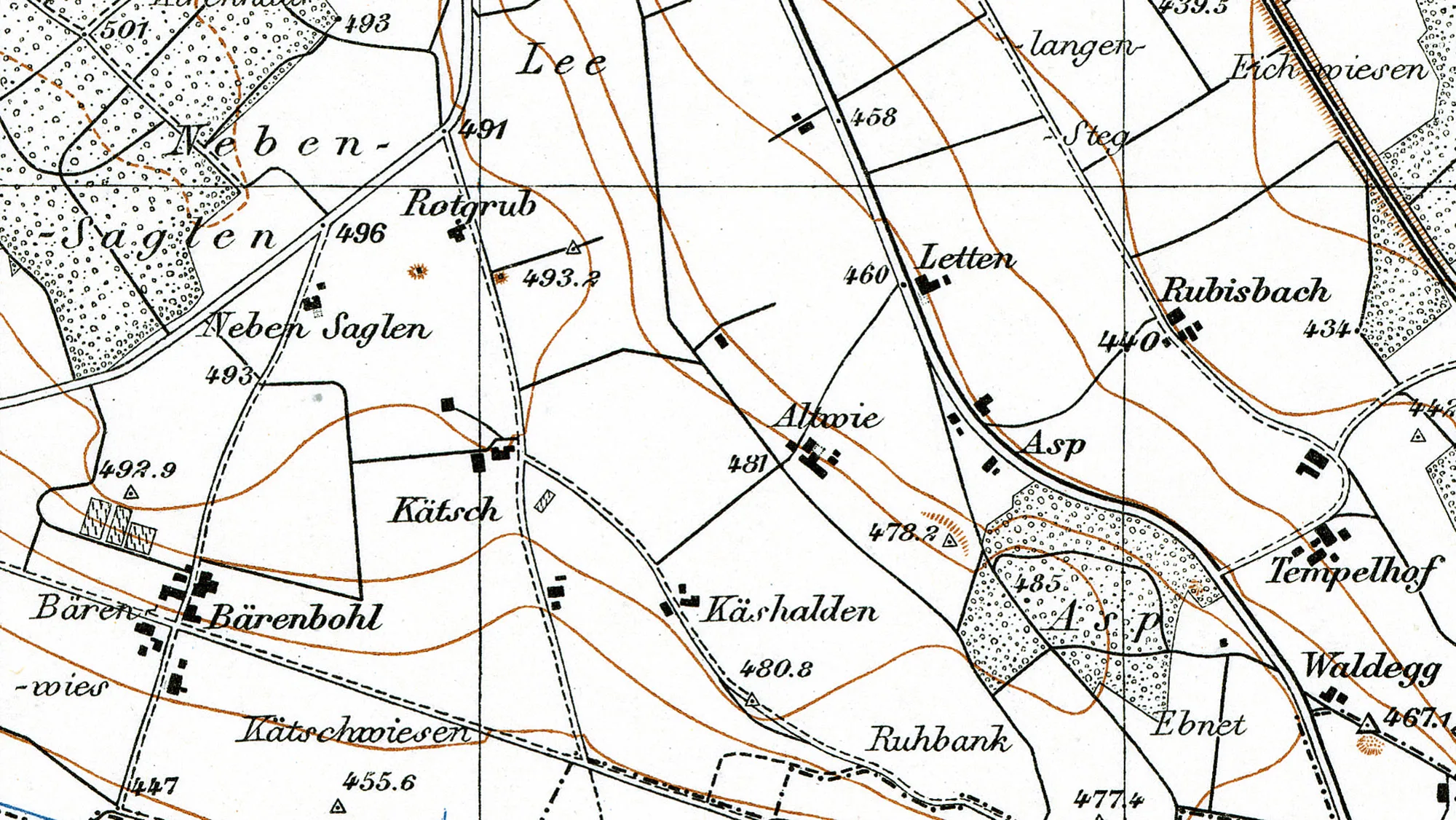

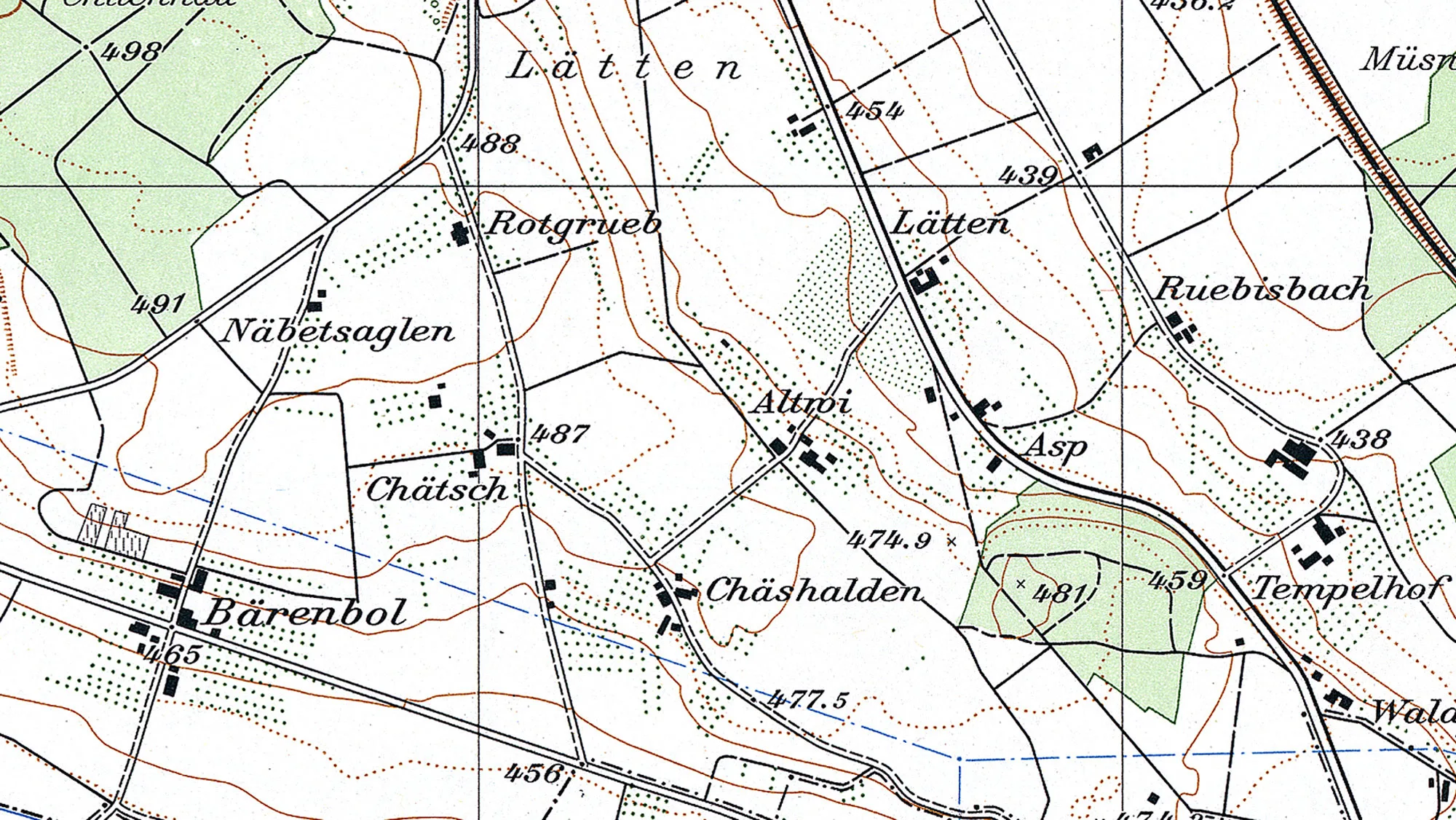

Swiss German and High German

But Guntram Saladin was preaching to the converted, even at the Federal Office of Topography. This was the age of spiritual national defence when everything that was considered ‘authentically Swiss’ was promoted – including dialect. However, some were critical of a radical ‘dialectisation’ of geographical names. For example, Zurich cartography professor Eduard Imhof pointed out that the coexistence of High German and dialect was actually typically Swiss:

Systematic use of dialect is a pipe dream […]. Our maps reflect Switzerland’s linguistic destiny – the coexistence of dialect and standard language. Is this worth losing sleep over?

A question of identity

As authority for deciding place names lies with the cantons, there is still a great deal of variation and regional difference in terms of the handling of dialect and standard language in Switzerland’s geographic names, even now in the 21st century. This is probably a good thing as at least one insight has emerged in almost 200 years of official map production: that artificial standardisation of geographical names, whether in favour of standard language or dialect, doesn’t go down well in Switzerland. As Eduard Imhof noted in 1945, the coexistence of dialect and standardised language is “Switzerland’s linguistic destiny” – and this has always been true for topographic maps of the country.