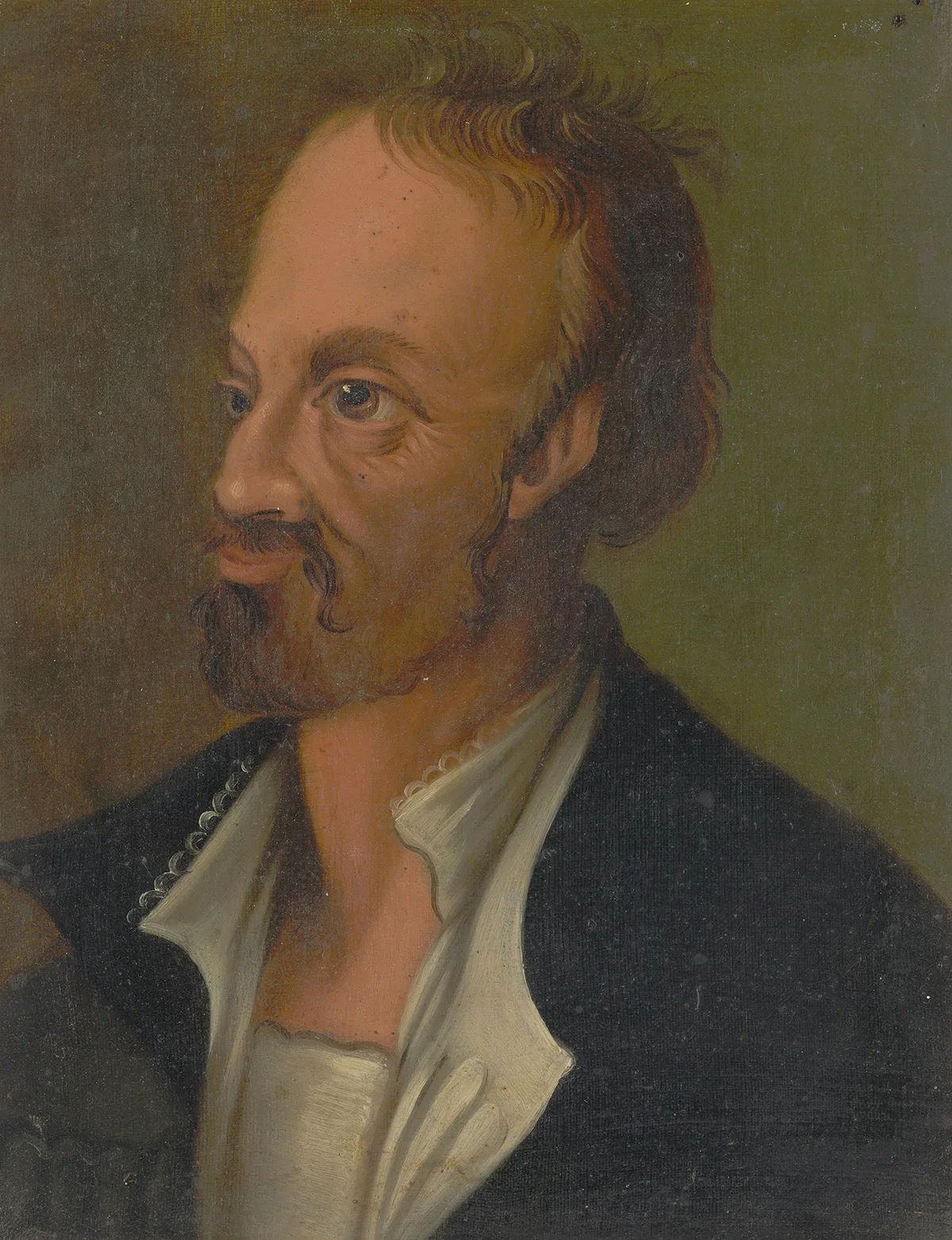

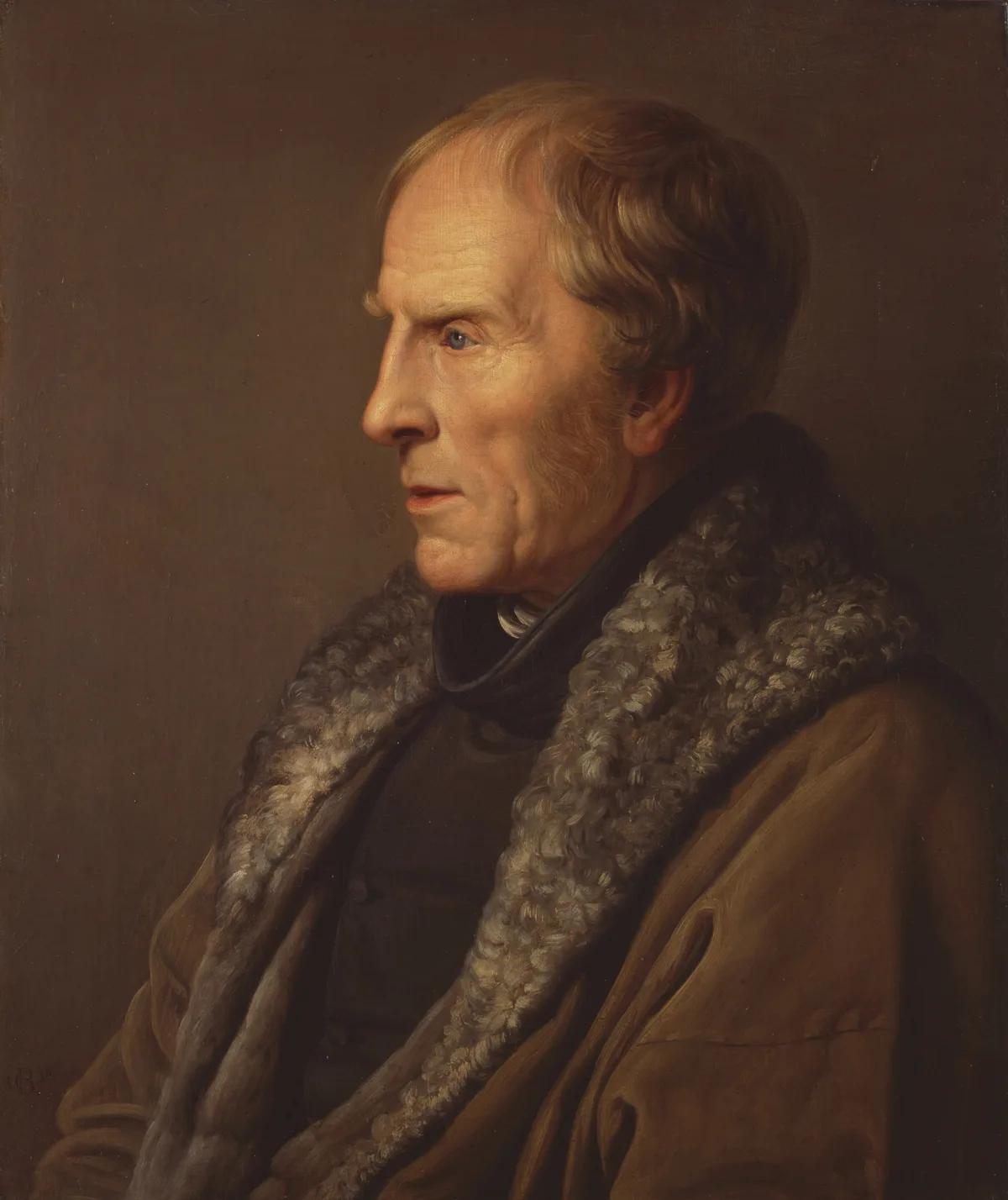

The two graves of Ulrich von Hutten

Humanist, reformer and freedom fighter Ulrich von Hutten (1488-1523) died on the island of Ufenau in Lake Zurich, to which he had fled as a victim of religious and political persecution. The urge to dedicate a monument to him has inspired poets and artists alike.