In search of snow

Switzerland and snow have a very special history. It ranges from skiing to avalanche research. As the planet heats up the snow is melting, and it’s happening here in Switzerland as well. What has happened? And how will it snow in the future? A search for clues.

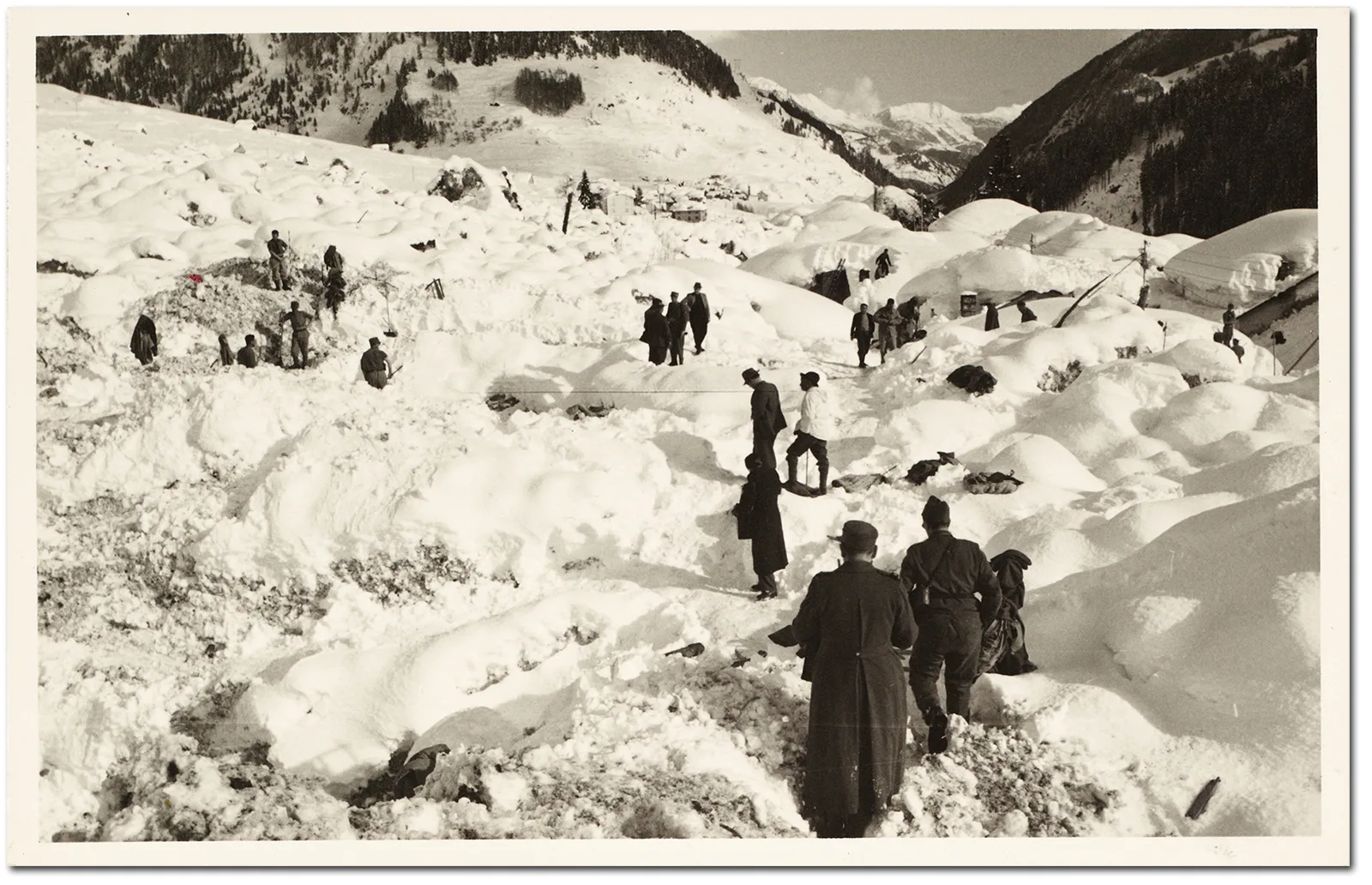

Avalanches

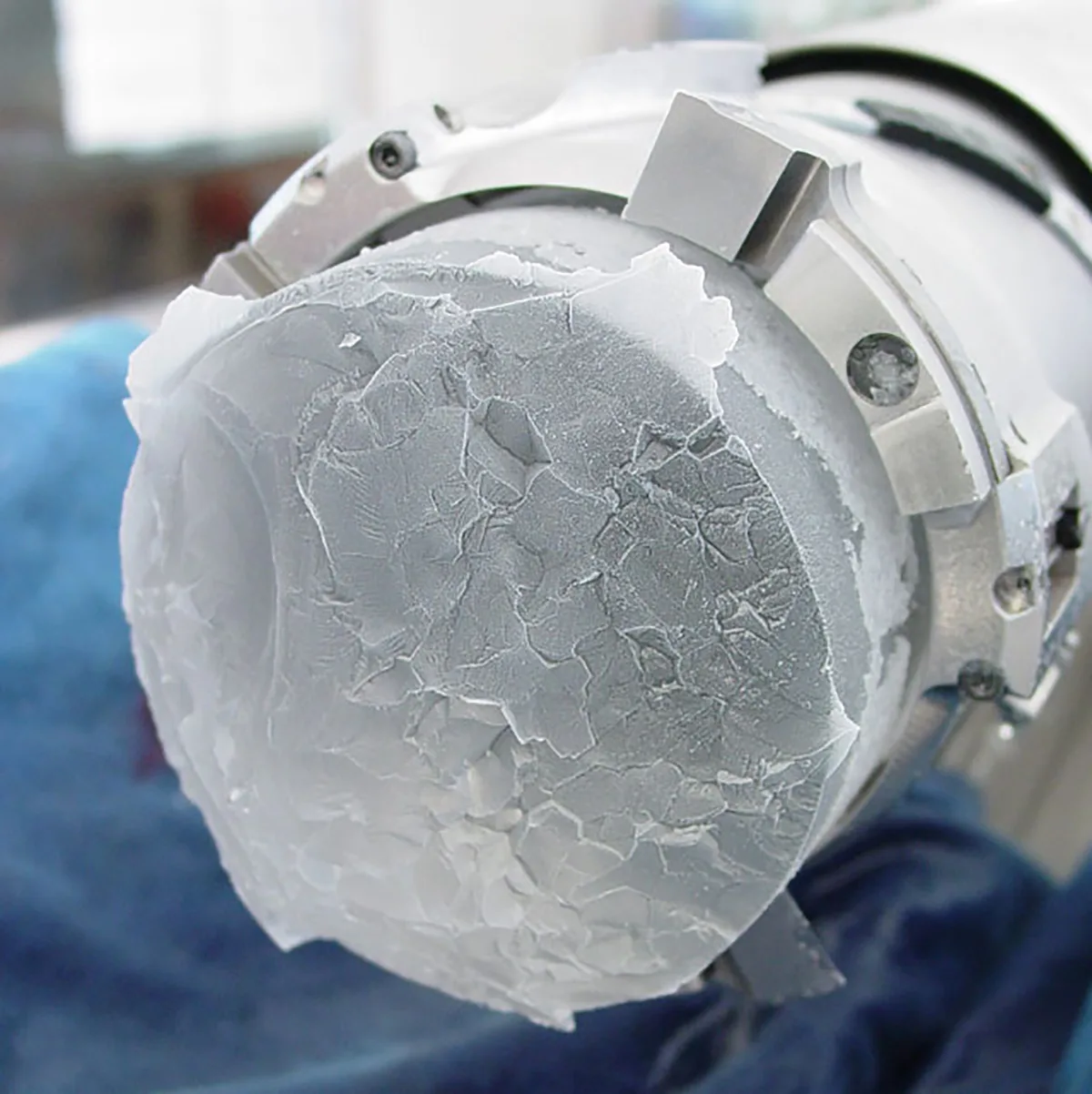

Drill cores

Forecasts

The snow of the future – Interview with Christoph Marty, Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research (in German). YouTube / Swiss National Library