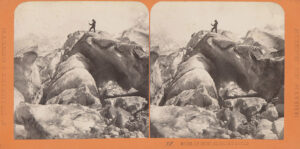

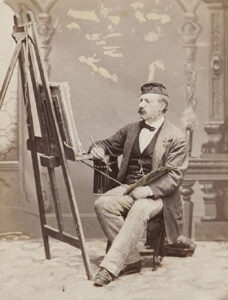

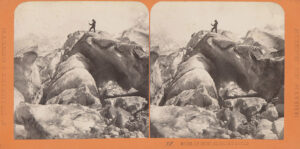

Calame’s awe-inspiring Alpine views

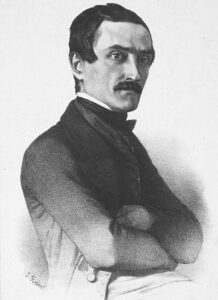

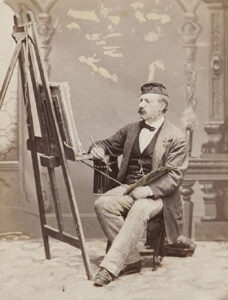

Alexandre Calame is considered one of the fathers of Alpine landscape painting. And it all started, figuratively speaking, with a storm.

Alexandre Calame is considered one of the fathers of Alpine landscape painting. And it all started, figuratively speaking, with a storm.