Eloquent witnesses to World War II: the sandstone reliefs in the Töss Valley

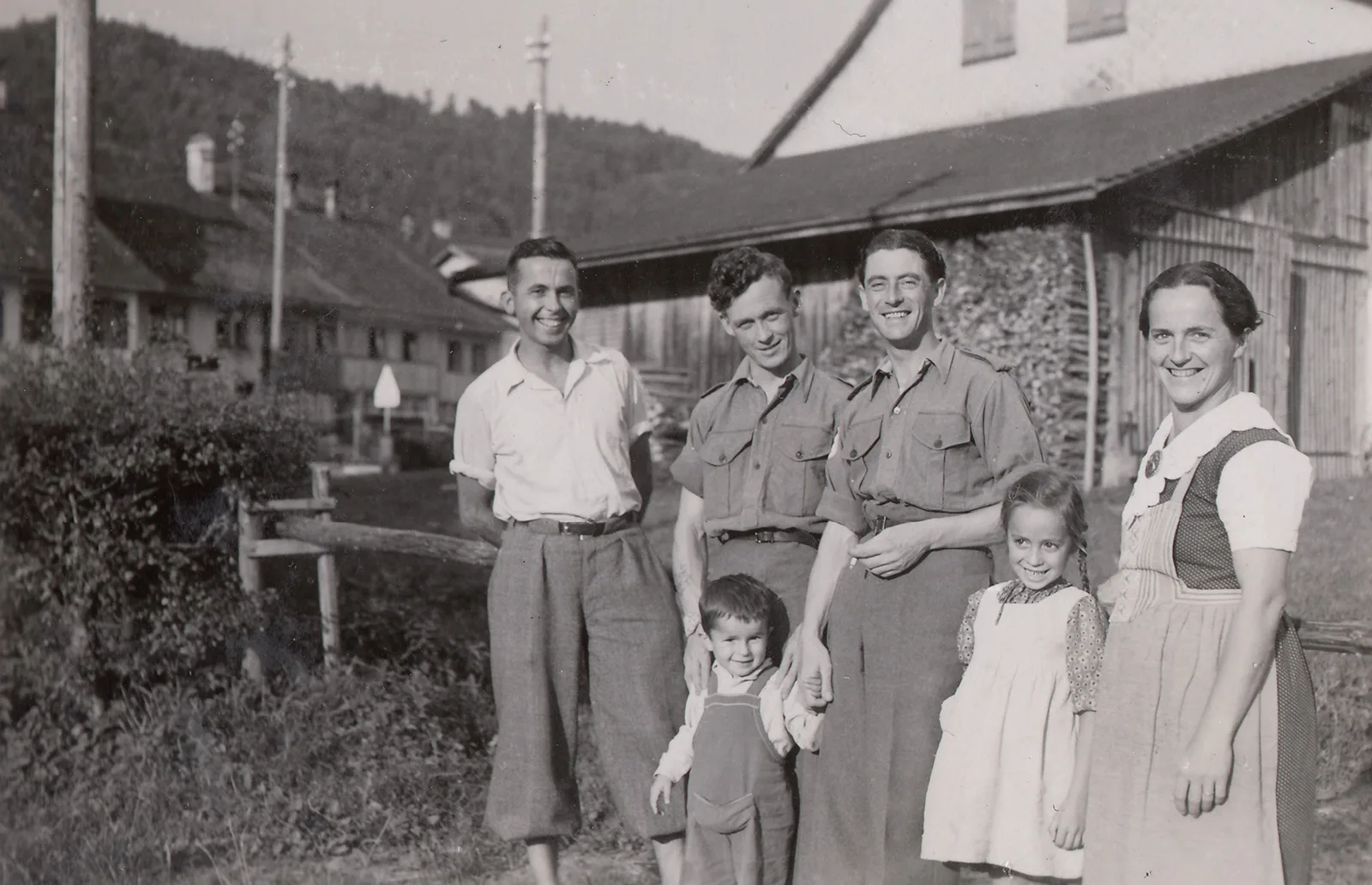

More than 100,000 soldiers from foreign armies were interned in Switzerland during World War II. Reminders of their presence can still be found today – in the Töss Valley in the Zurich Oberland, for instance.