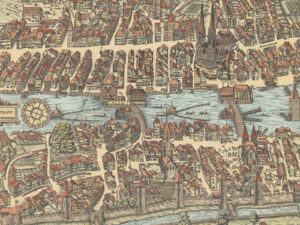

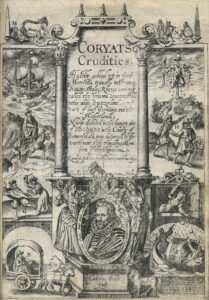

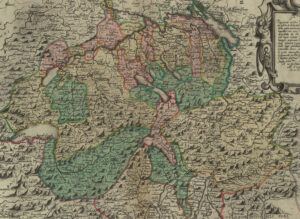

A journey across Switzerland in 1608

Drinking and bathing habits, fashion preferences, dealing with death: the astonishing observations of English traveller Thomas Coryat (1577-1617) in early 17th-century Switzerland.

Me thinks it had beene much better to have reserved the arrow with which [Tell] shot through the tyrant, then the sword that he wore.

A man may live as cheape here as in any City of Switzerland or Germanie.

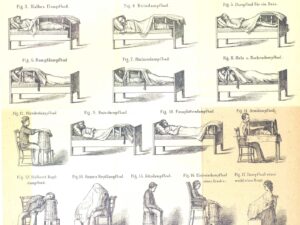

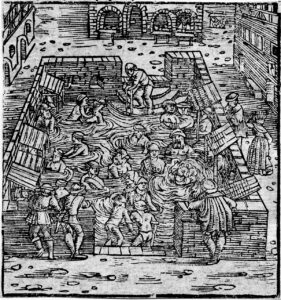

Men and women bathing themselves together naked from the middle upward in one bathe: whereof some of the women were wives (as I was told) and the men partly bachelers, and partly married men, but not the husbands of the same women.

I observed many women of this Citie to be as beautifull and faire as any I saw in all my travels.