In the days when candle wicks still had to be trimmed…

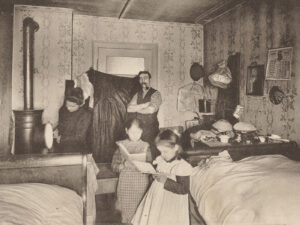

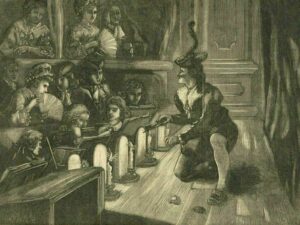

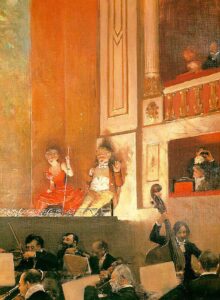

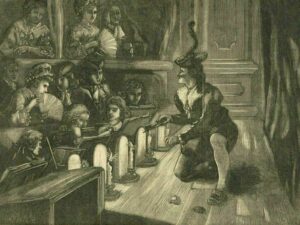

Until the first half of the 19th century, a pair of candle scissors was an essential tool in every home, and the wick-trimming tool of the lighting technician in every major theatre.

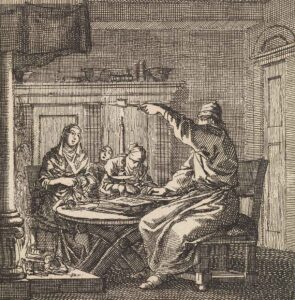

Maidservant with candle care tool, which she has fastened to a belt around her waist. Painting by Cornelis Troost, Amsterdam, 1737. Mauritshuis, Den Haag

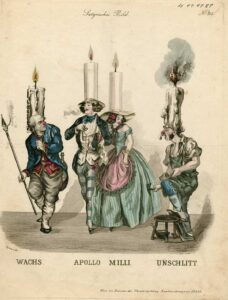

A “candle revolution” thanks to stearin and paraffin

I cannot think of a better invention than lights that keep burning without needing to be trimmed.