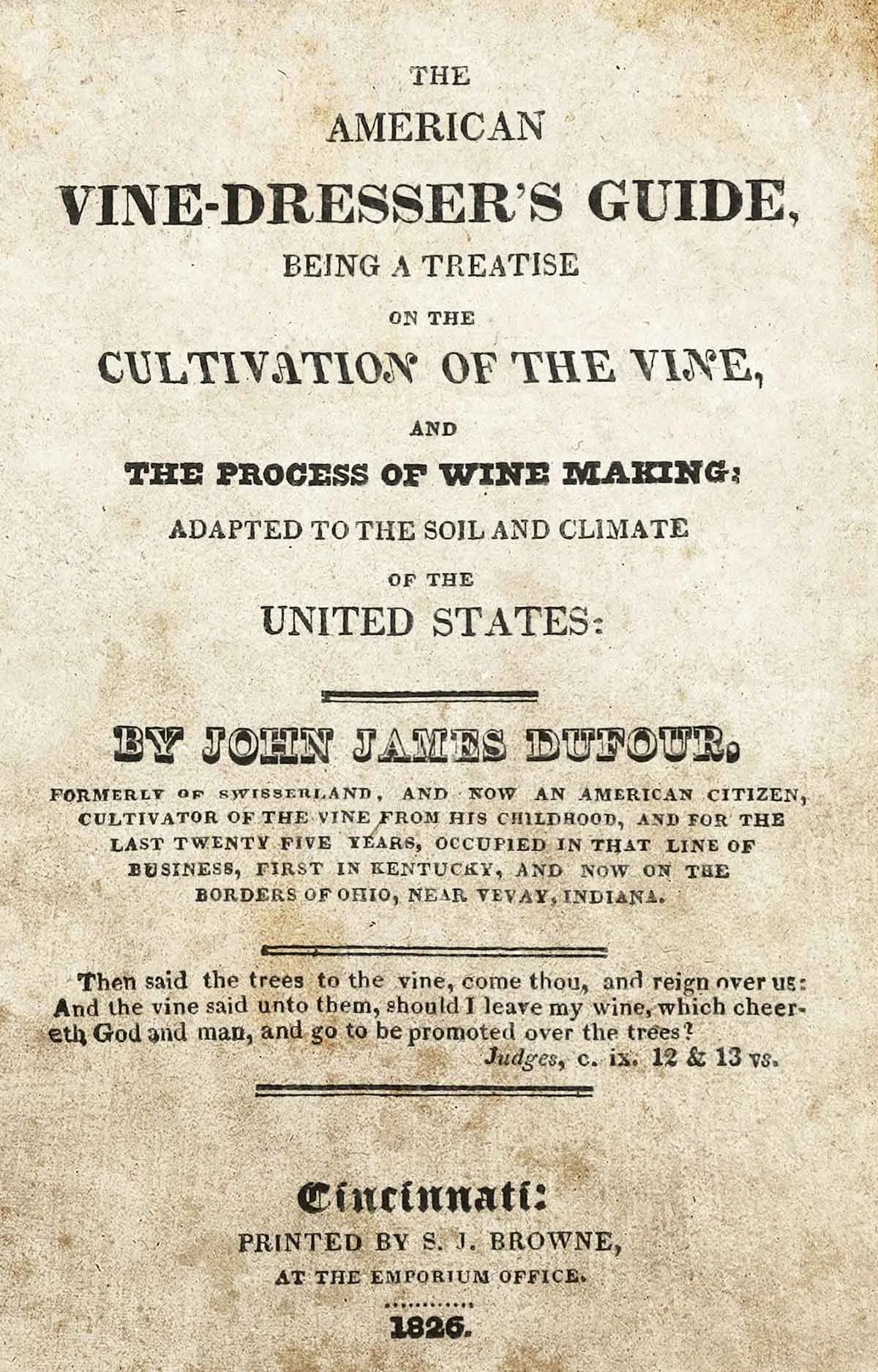

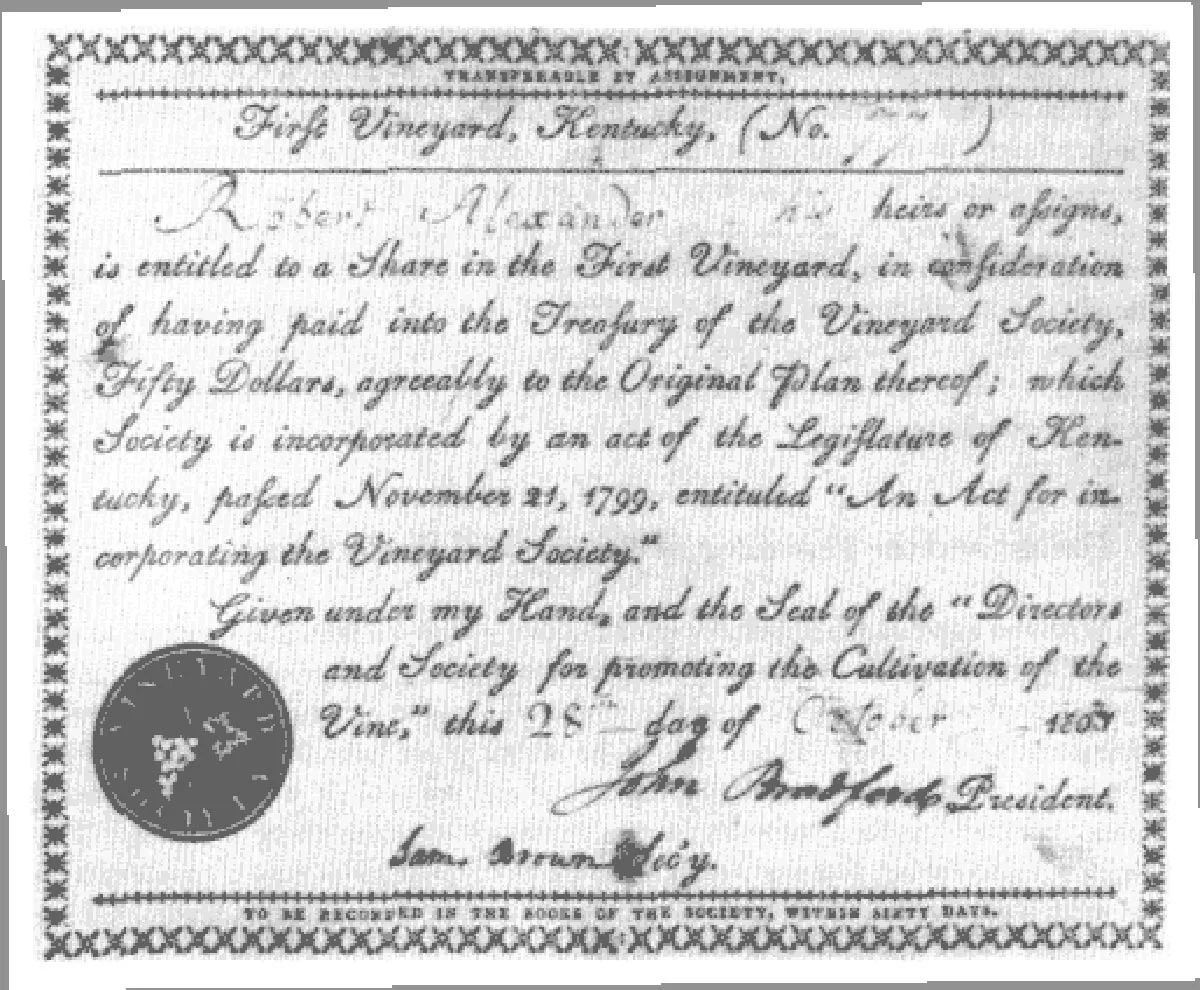

The first commercial winery in the United States – established by a Swiss immigrant!

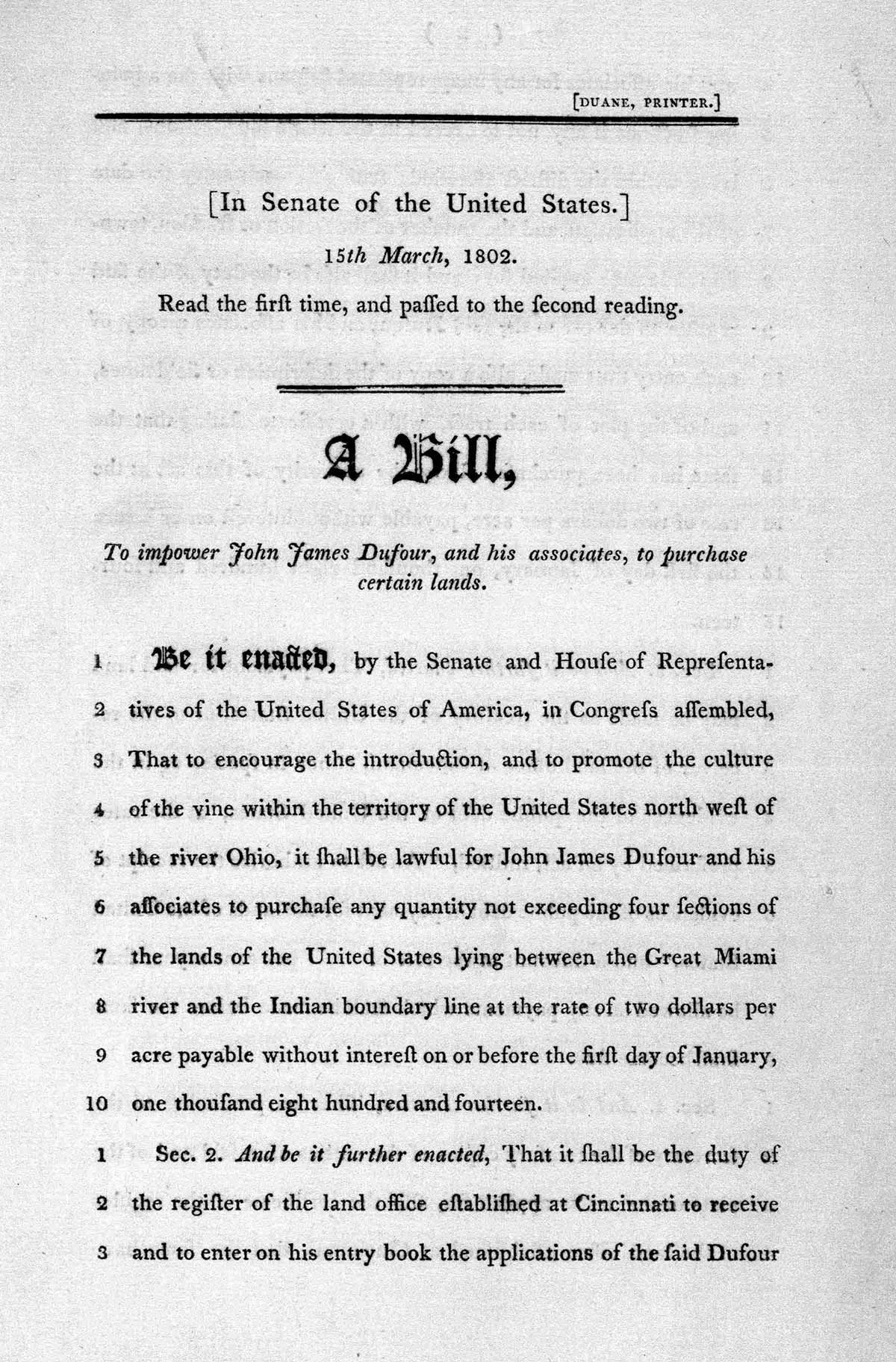

In 1796, Jean-Jacques Dufour emigrated from the Lake Geneva region with the stated aim of becoming a successful winegrower in distant America. The Swiss grower founded the colony of Vevay, Indiana, which did indeed manage to produce wine.

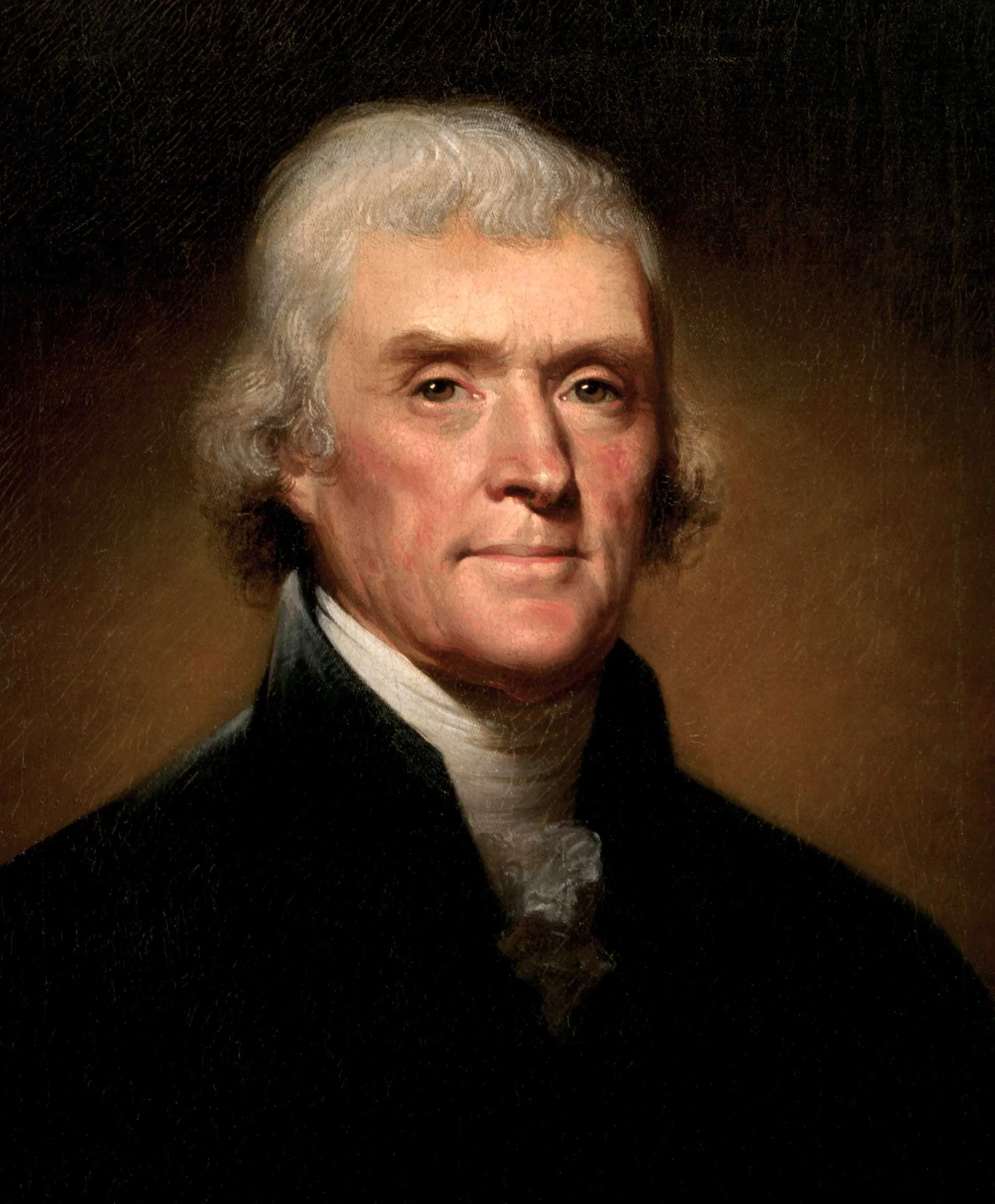

Tasting for the President