The food on the working man’s table

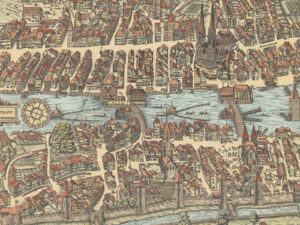

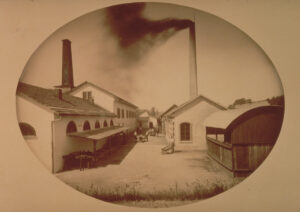

The process of industrialisation witnessed its first peak in Switzerland between 1850 and 1900. This upheaval also transformed the way food was produced and what people ate.

Film trailer from 1958 (in German). YouTube

Beer as a luxury product