Swiss mercenaries in North America

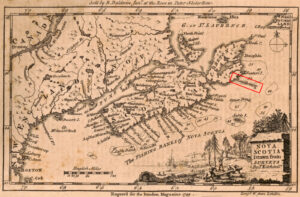

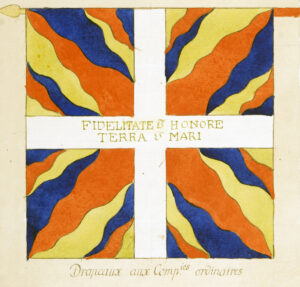

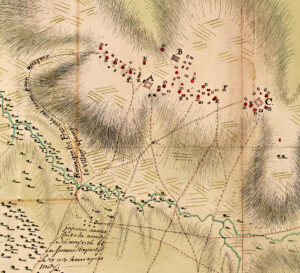

Although not officially permitted, Swiss mercenaries were active in North America during the late Baroque period. Swiss fighters of the Karrer Infantry Regiment lost their lives in Mississippi during the war between France and the Native American tribes.