The history of urbanisation and affordable housing in Switzerland

Housing shortages first became a hot topic in Switzerland in the second half of the 19th century. At the time, the issue was referred to as the ‘workers’ housing question’. It presented a challenge to municipal governments and even led to riots.

The momentum of industrialisation caused towns and cities to grow. And the growth accelerated, as shown by the figures for Basel: it initially took 70 years for the city’s population to double up to the mid-19th century, another 30 years for it to double again, and just the last two decades of the 19th century to double for a third time. Meanwhile, the city of Zurich grew by 9,400 people every year between 1893 and 1897 – the period when the National Museum Zurich was being built. That equates to a growth rate of 7.3% and is six times higher than the city’s current rate of growth. Nationwide, the urban population grew sixfold between 1850 and 1910. In no other census period was urbanisation as strong as between 1888 and 1900.

In short, there was not enough housing for workers and their families. But the housing shortage was not only in cities, it was also in small towns like Arbon, which saw rapid expansion at the time, primarily due to the strong growth of the companies Saurer and Heine. Housing was even a problem in rural areas, such as the lower Reuss valley in the canton of Uri, which, after the opening of the Gotthard railway, became a well-connected and therefore attractive location for industry.

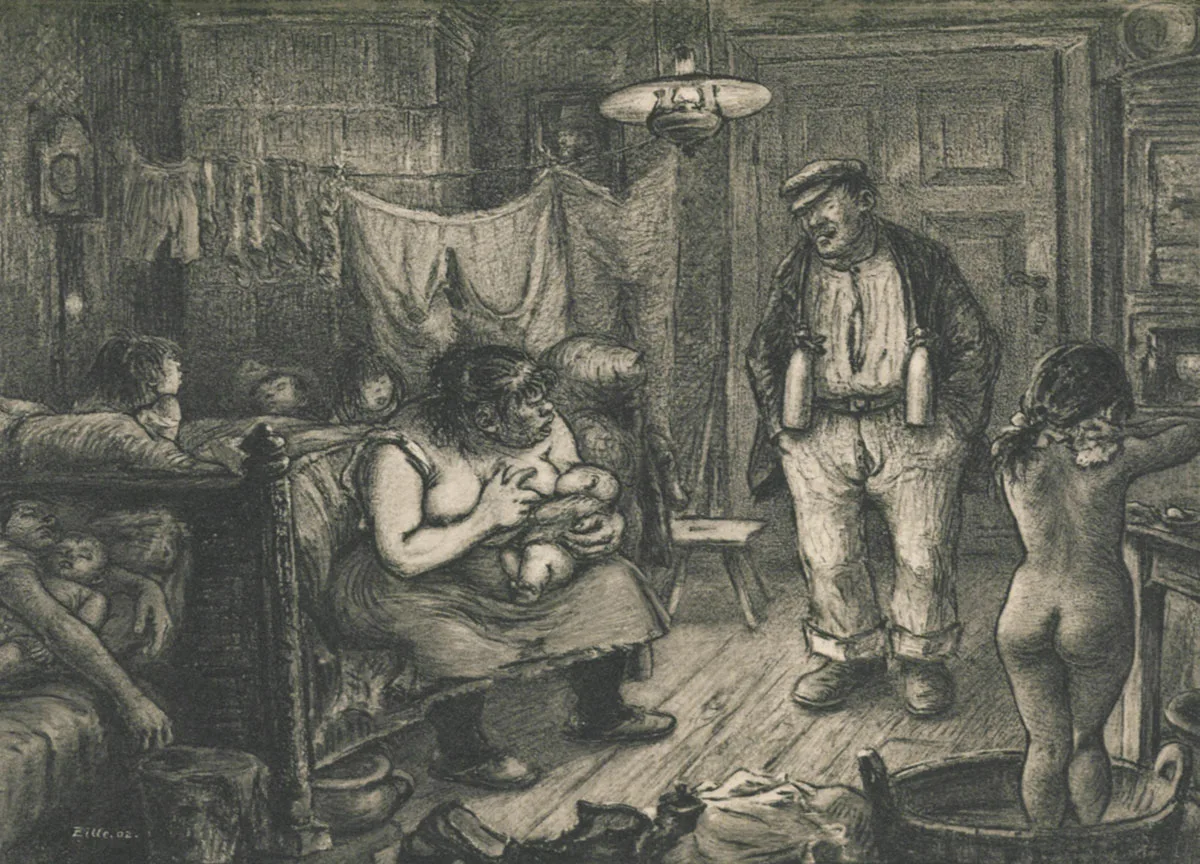

Night lodgers and boarders

To be able to afford the high rents, many people took in lodgers to live in specially separated parts of their homes. Or they accommodated so-called Schlafgänger, or ‘night lodgers’ to whom they would rent out a bed in their own room, sometimes in eight-hour shifts. For a time, lodgers and Schlafgänger made up over 15% of Zurich’s population. And there were always homeless families in Zurich and Bern who were forced to sleep in barns, stables, attics and under bridges.

Public debate

Before the survey in Zurich was completed, the City Council recorded in its annual report for 1894: “Numerous on-site observations have led us to conclude that the question of workers’ accommodation has reached a stage that is likely to cause a public outcry.” The City Council appeared concerned as to whether the “overcrowding” of dwellings, “which was already resulting in the most severe health, moral and social effects would inevitably become even worse if far-reaching and resolute action was not taken to counter the scourge that threatened to become chronic”.

According to the City Council, conditions would not improve but only deteriorate, “if housing provision was left to its own devices, i.e. property developers, and if society and employers did not intervene to regulate the housing situation in the public interest”. Zurich City Council decided to “set up a committee from among its members”, “with the task of carrying out a thorough examination of the issue of workers’ housing”.

No initial tangible results

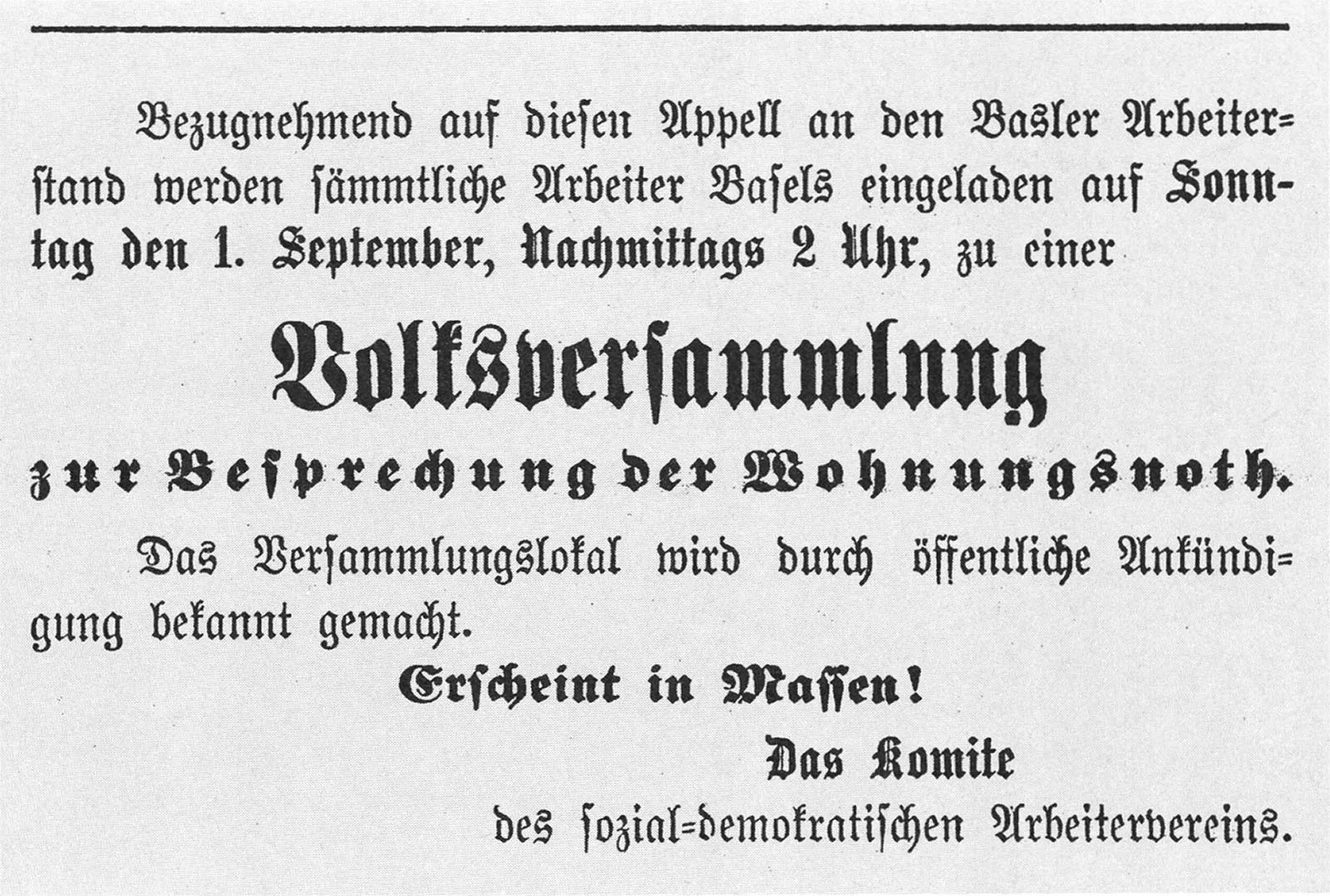

A major reason for strikes and conflicts

The housing shortage – as well as the issue of wages – was not only one of the main reasons behind organised strikes, but also a series of conflicts “that broke out because of ‘trivialities’ and ‘petty matters’ without any plausible or concrete demands.” Examples of such conflicts are the Käfigturm riots of 1893 in Bern, the Italian riots in Zurich in 1896 and the Arbon riots of 1902. Fritzsche argued that the question of workers’ housing was much more important than workplace conditions in the emergence of labour organisations, class consciousness and ultimately the class struggle.