Bringing literature to the masses

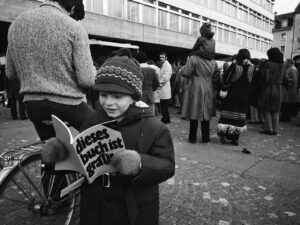

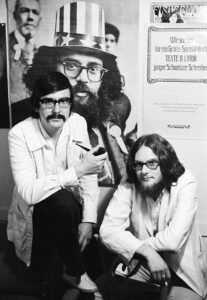

In 1971, two young creatives captured the world’s attention with a free book. They distributed the work throughout German-speaking Switzerland with the backing of prominent literary figures.

TV report on the free book (in German). SRF

The photos of the action «free book» were taken by Swiss photographer Eric Bachmann (1940–2019). He realised numerous reports in Switzerland and internationally and photographed countless 20th century figures such as Muhammad Ali, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Bob Marley, Astrid Lindgren and many more. His archive is kept in Kaiserstuhl and part of it is accessible online at ericbachmann.ch.