Switzerland: the reluctant host of Italian guest workers

In the 1960s, Switzerland faced a dilemma regarding its Italian guest workers: their labour was desperately needed, their presence in society less so...

The economic boom in Switzerland meant that demand for workers rose steadily during the 1950s. It was not long before hundreds of thousands of Italians were working on building sites, in factories and in private houses. They couldn’t even apply for a residence permit until they had been working in Switzerland for at least ten years. And those who didn’t work were not allowed to stay – with devastating implications for children who had to stay illegally or grow up separated from their parents.

In November 1961, an ‘informal visit’ by the Italian labour minister caused a frenzy in Switzerland. Fiorentino Sullo wanted to see the living and working conditions of his compatriots for himself. He visited factories, spoke to Italian workers, and attended official engagements hosted by cantonal and municipal authorities. The warm reception was intended to reinforce the good relations between the two countries. But diplomacy wasn’t exactly Sullo’s strong suit. In a tone described by the Catholic Basler Volksblatt as “not going down well with the Swiss”, he criticised the working conditions of Italian guest workers and the backwardness of the social insurance system. By openly threatening that Italy would make it more difficult to recruit workers unless his demands were met, Sullo managed to alienate his hosts.

Both the Swiss left-wing and right-wing media immediately looked southwards, with reports of people in Sicily “walking around with empty stomachs and having to eat herbs and snails.” One report quoted a woman in Italy who had “given blood, sweat and tears her whole life” and still didn’t get a pension. The general feeling was that if this “man named Sullo” really cared about the fate of Italian workers, he had “plenty to do at home”.

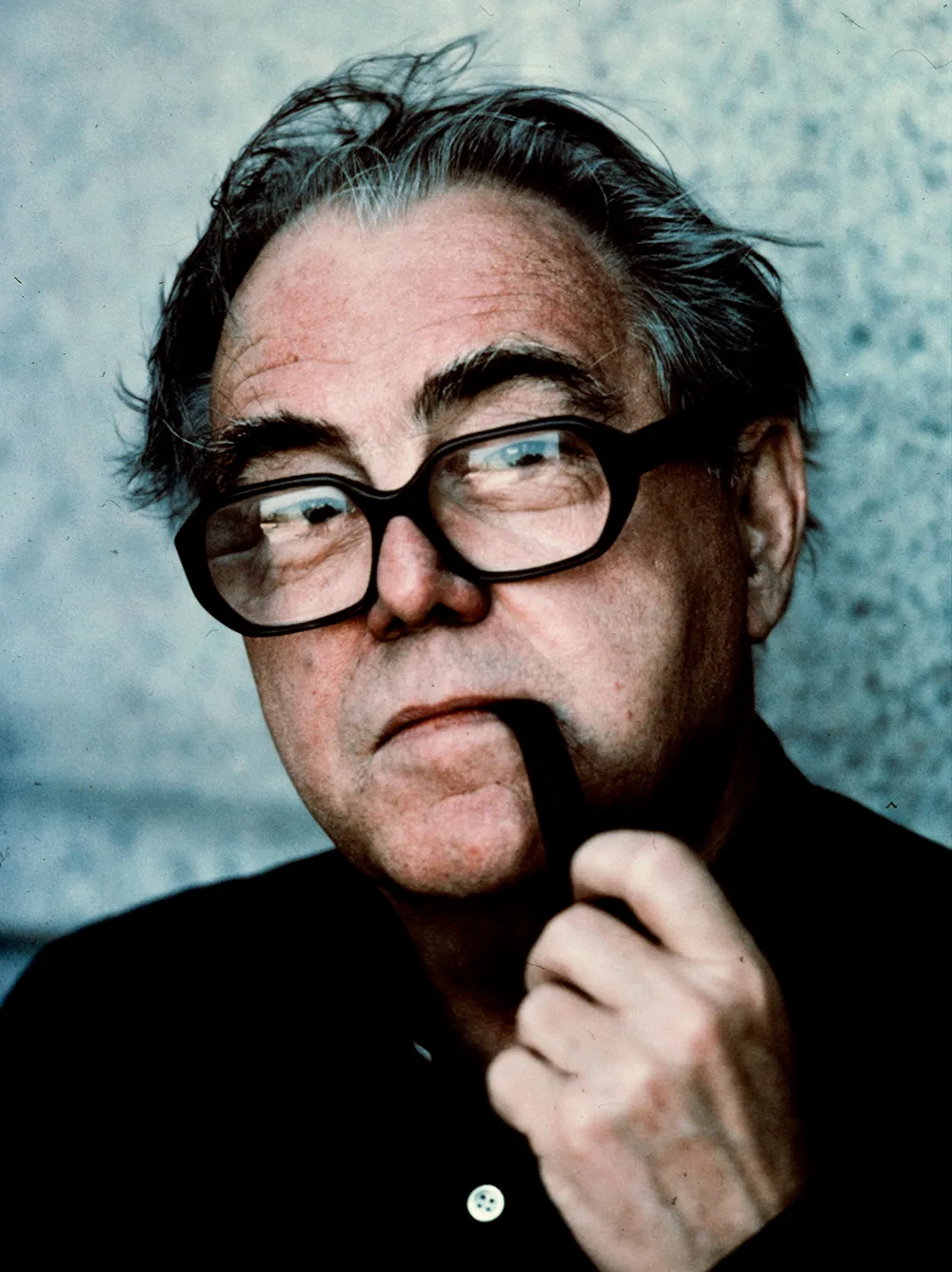

While the Parliament was still debating the ratification of the agreement, anti-Italian demonstrations took place. The Nationale Aktion continued to grow, and in 1967 it sent its first National Councillor, James Schwarzenbach, to Bern. His popular initiative to limit the foreign labour force to ten percent of the population was put to the vote in 1970. The all-male electorate rejected it, but the initiative, which was opposed by all the parties in the Federal Council and business organisations, was widely supported.

Nowadays, Italian influences are omnipresent in Switzerland and descendants of Italian immigrants are a common feature in the workplace and in public life. It’s hard to believe the extent to which Italians were painted as a threat to Swissness just half a century ago. But the policy of marginalisation, which culminated in Schwarzenbach’s initiative, did not disappear; it was just directed at people from other places instead. As historian Angelo Maiolino says, “the roles are the same, only the actors have changed”.