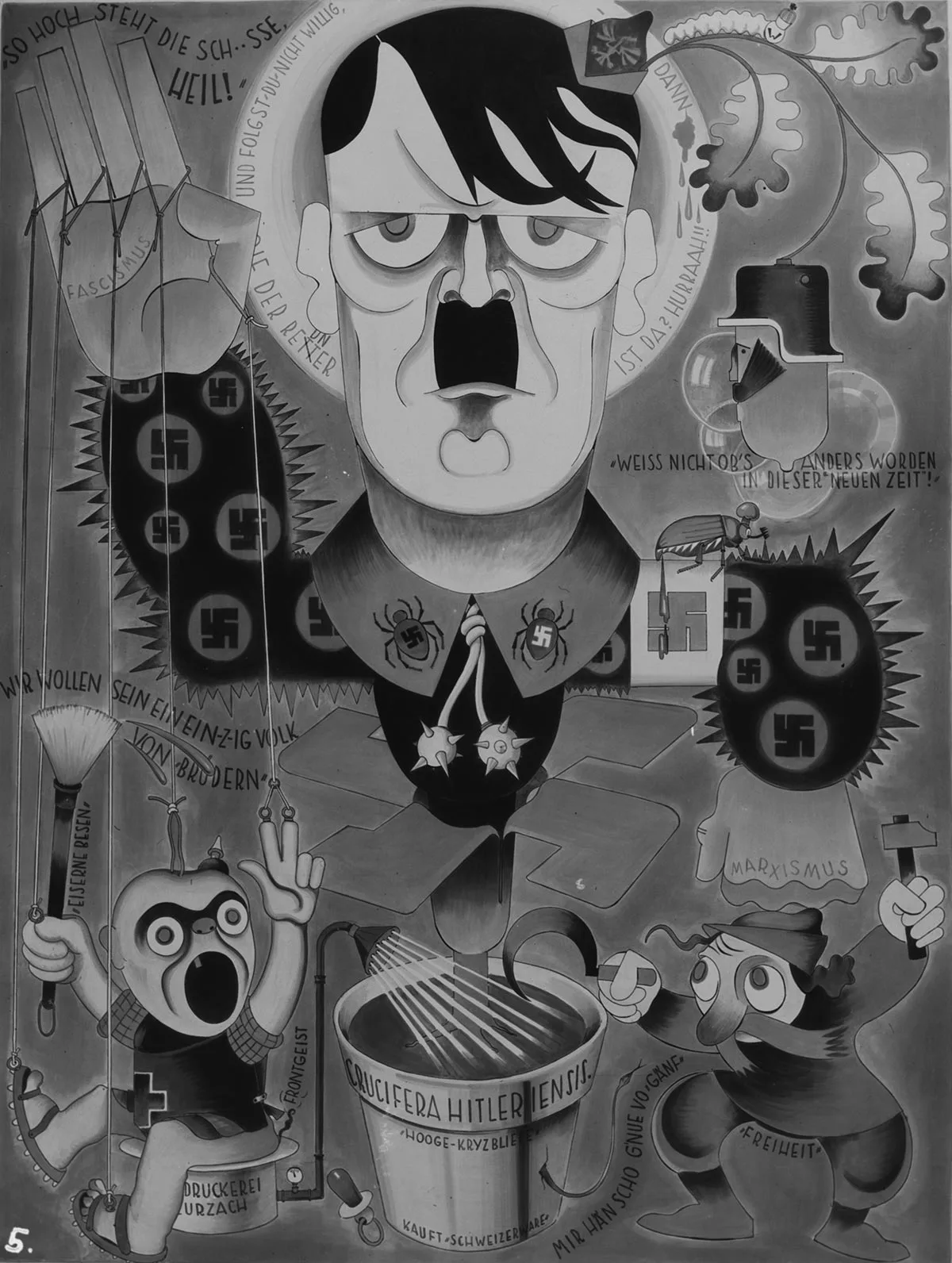

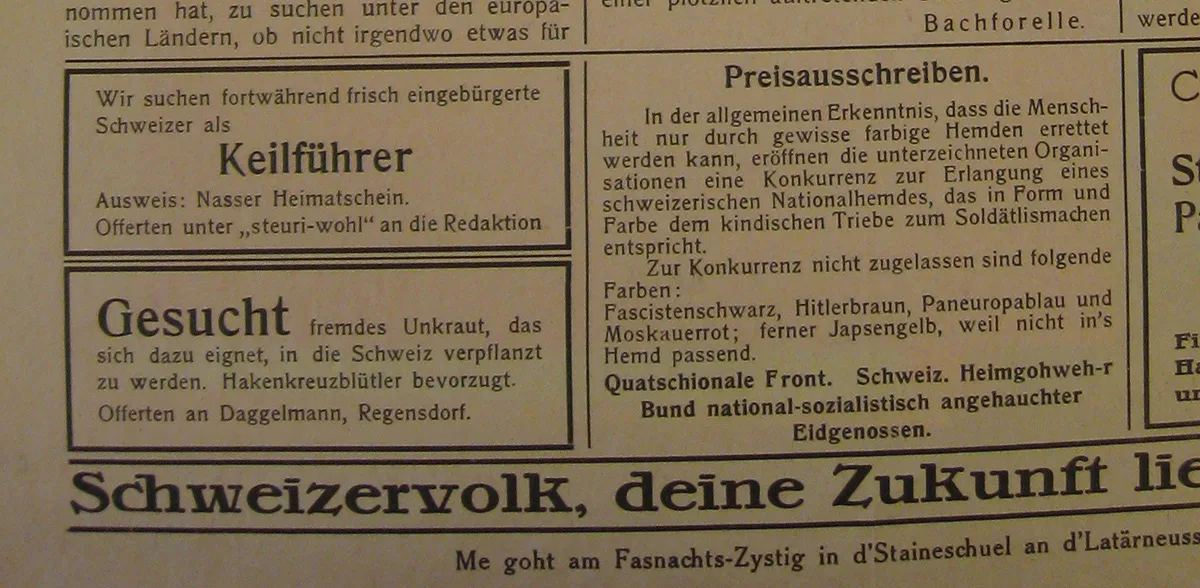

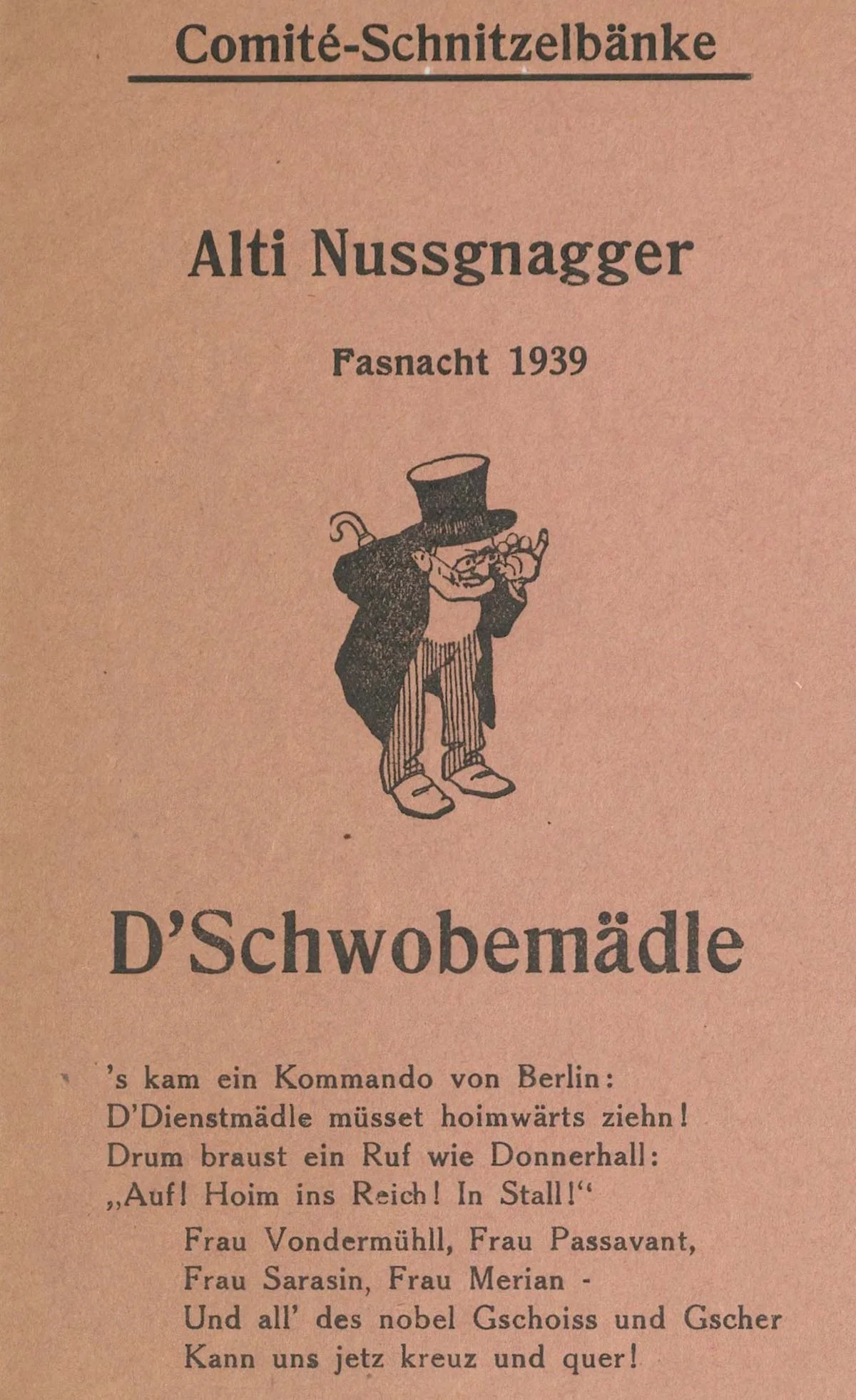

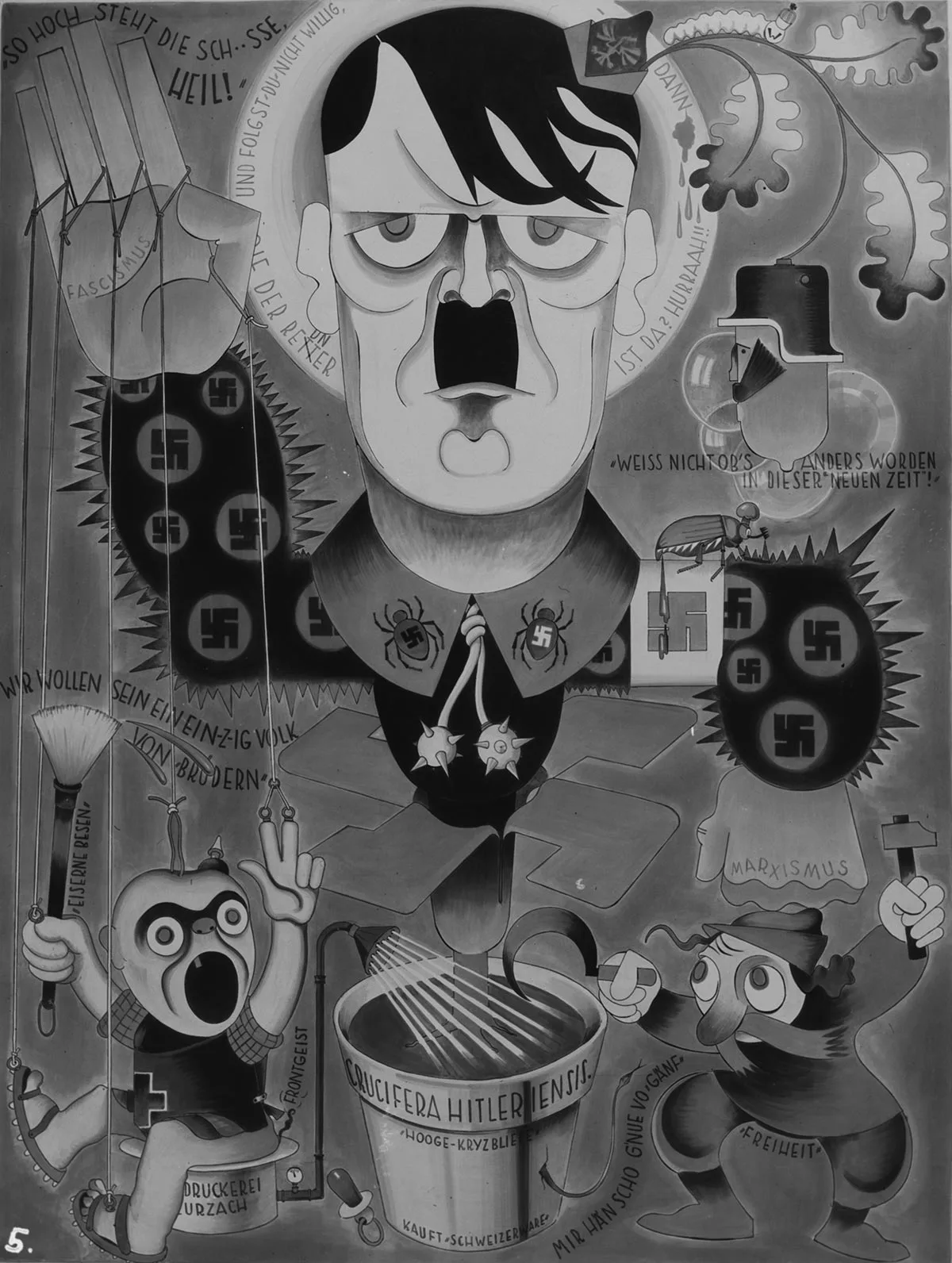

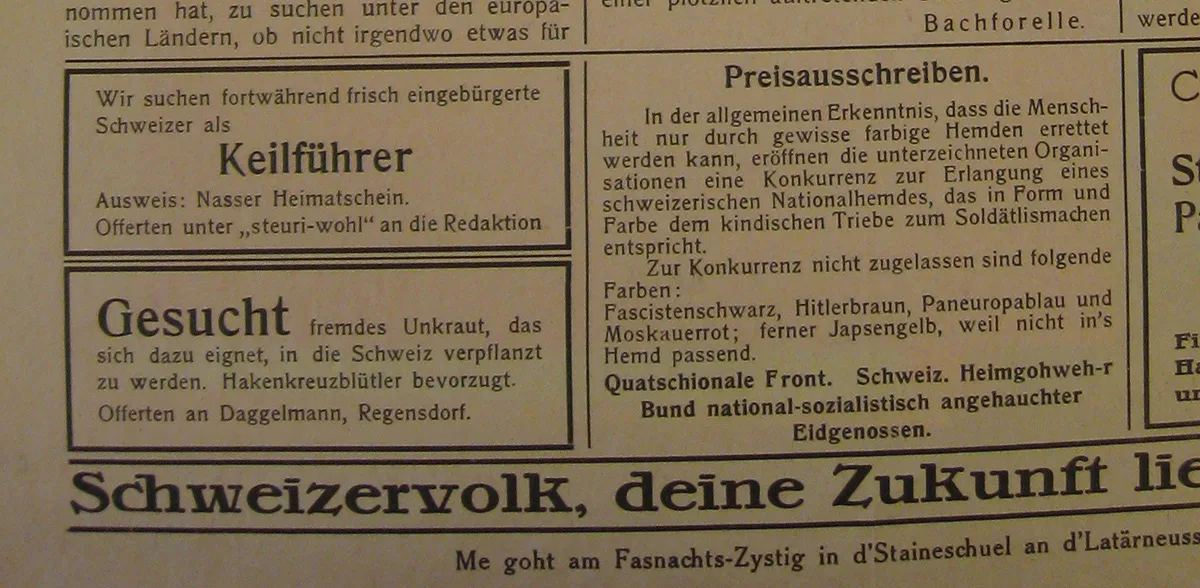

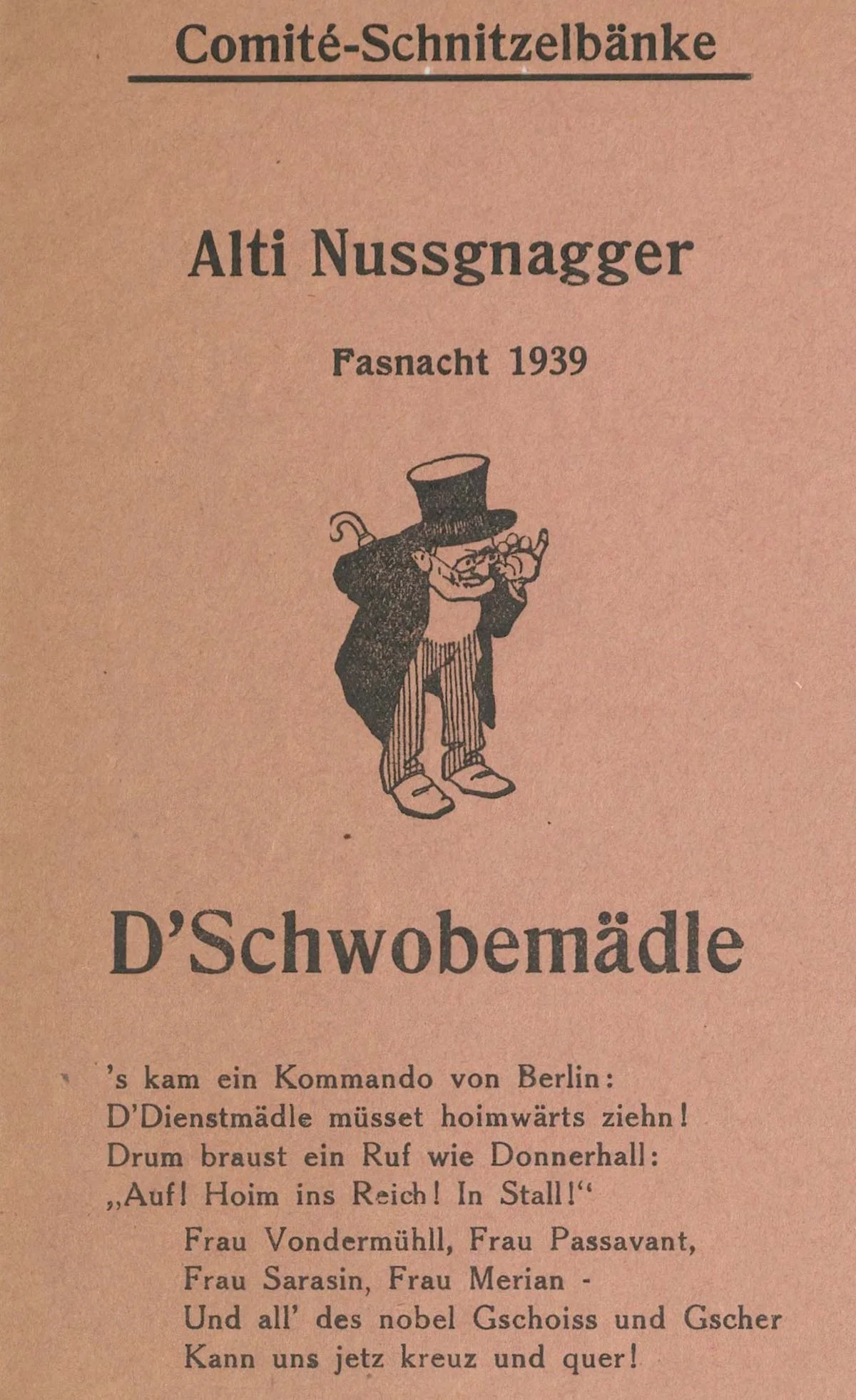

Basel Carnival in the 1930s: don’t upset the Nazis

At Basel Carnival, anyone and anything is fair game. But from 1933 things got tricky.

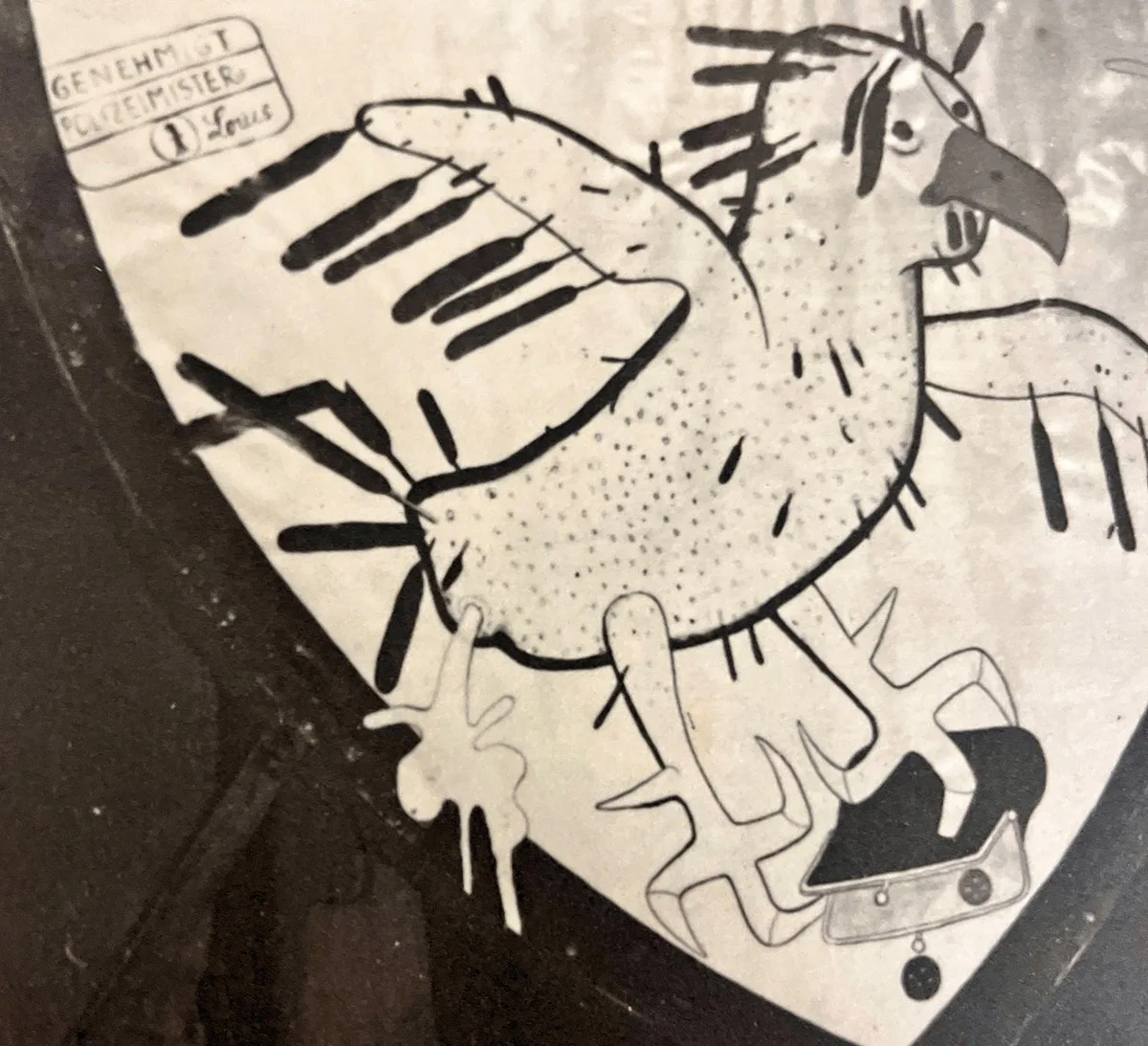

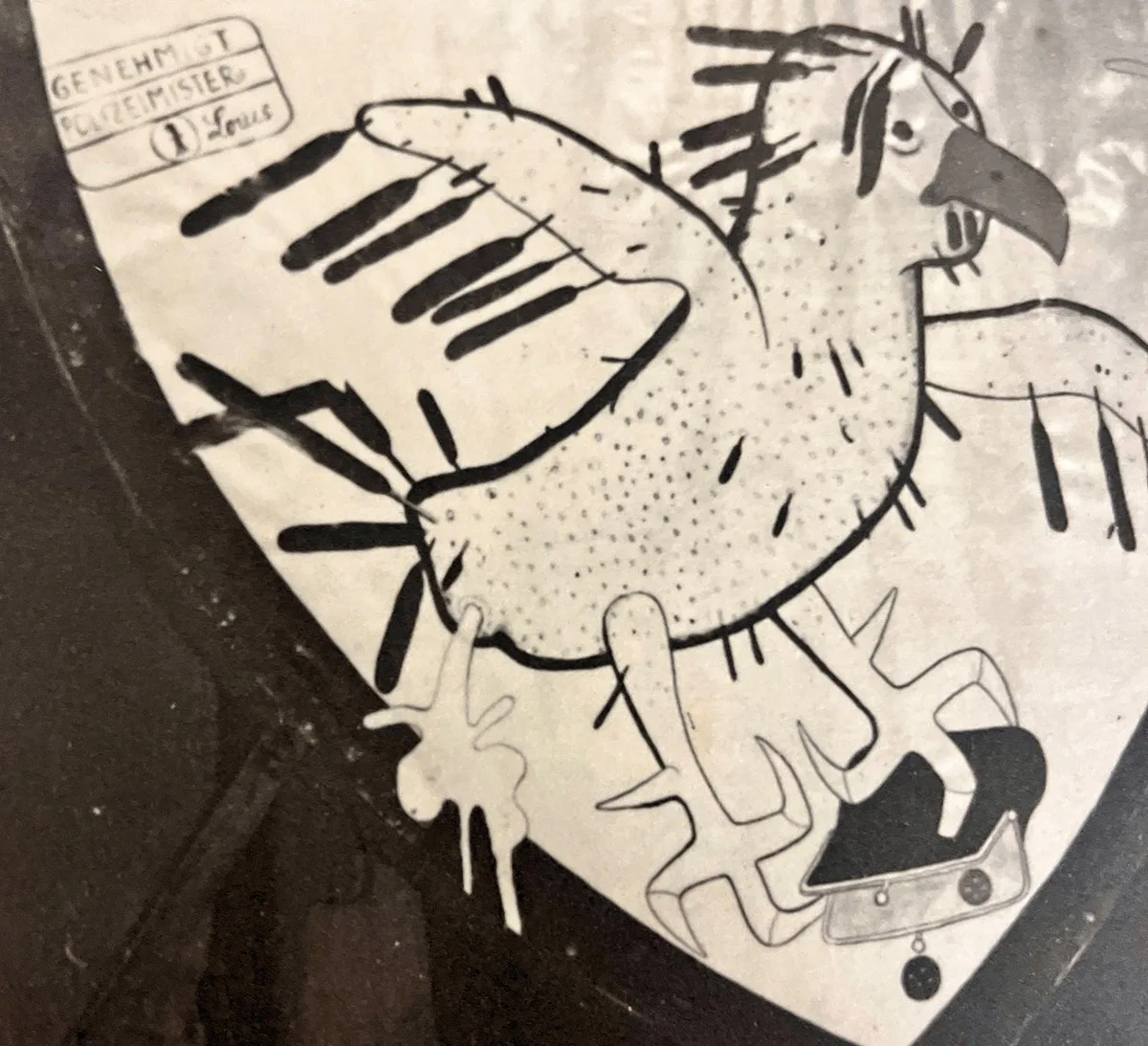

A police department on edge

At Basel Carnival, anyone and anything is fair game. But from 1933 things got tricky.