Swiss National Museum

The synagogues of Lengnau and Endingen

In the Surbtal Valley, Aargau, the first synagogues in Switzerland were built in the ‘Jew villages’ of Lengnau and Endingen. Even today, they bear witness to the eventful history of Jewish settlement in Switzerland.

Towards the end of the 16th century, the county of Baden registered the settlement of the first Jewish families. Specifically, there is a documented Jewish presence in the parish of Lengnau since 1622, and in the neighbouring village of Endingen from 1678, although their arrival – fleeing the turmoil of the Thirty Years’ War – can be assumed to be earlier. Other Jewish newcomers arrived, from Alsace and the Vorarlberg Rhine Valley, in these hamlets, which quickly become known, from one end of the country to the other, as ‘Jew villages’.

In 1696, the local bailiff (Landvogt) of the county of Baden, representing the Acht Alten Orte (the confederation of eight old cantons), issued the first charter of protection and safe conduct (known as a Schutzbrief) to the Jews. This charter had to be renewed every 16 years (this was done for the last time in 1792) and, in addition to various taxes and levies, it also set out the rules of public authority under which the Jews were required to live. They were not allowed to own land, could only marry a foreign Jewess if she brought 500 guilders into the marriage, and were forbidden to live under the same roof as Christians. This restriction was cleverly circumvented by having two separate entrances, an architectonic peculiarity which can still be seen today, as depicted by Charles Lewinsky in his epic family saga Melnitz, set in the Surbtal Valley: ‘In the other half of the house, with its own entrance door and its own staircase, in order to satisfy the form of the law according to which Christians and Jews may not live in the same building, lived the landlord, the tailor Oggenfuss, with his wife and three children: friendly enough people, if you knew how to take them. They maintained good neighbourly relations, which meant each household kept a benevolent eye on the other. The Oggenfuss family, with the practiced blindness of people who live closer to others than they would really like, had contrived not to notice the death of Uncle Melnitz and all the mourners coming to the house for seven days.’

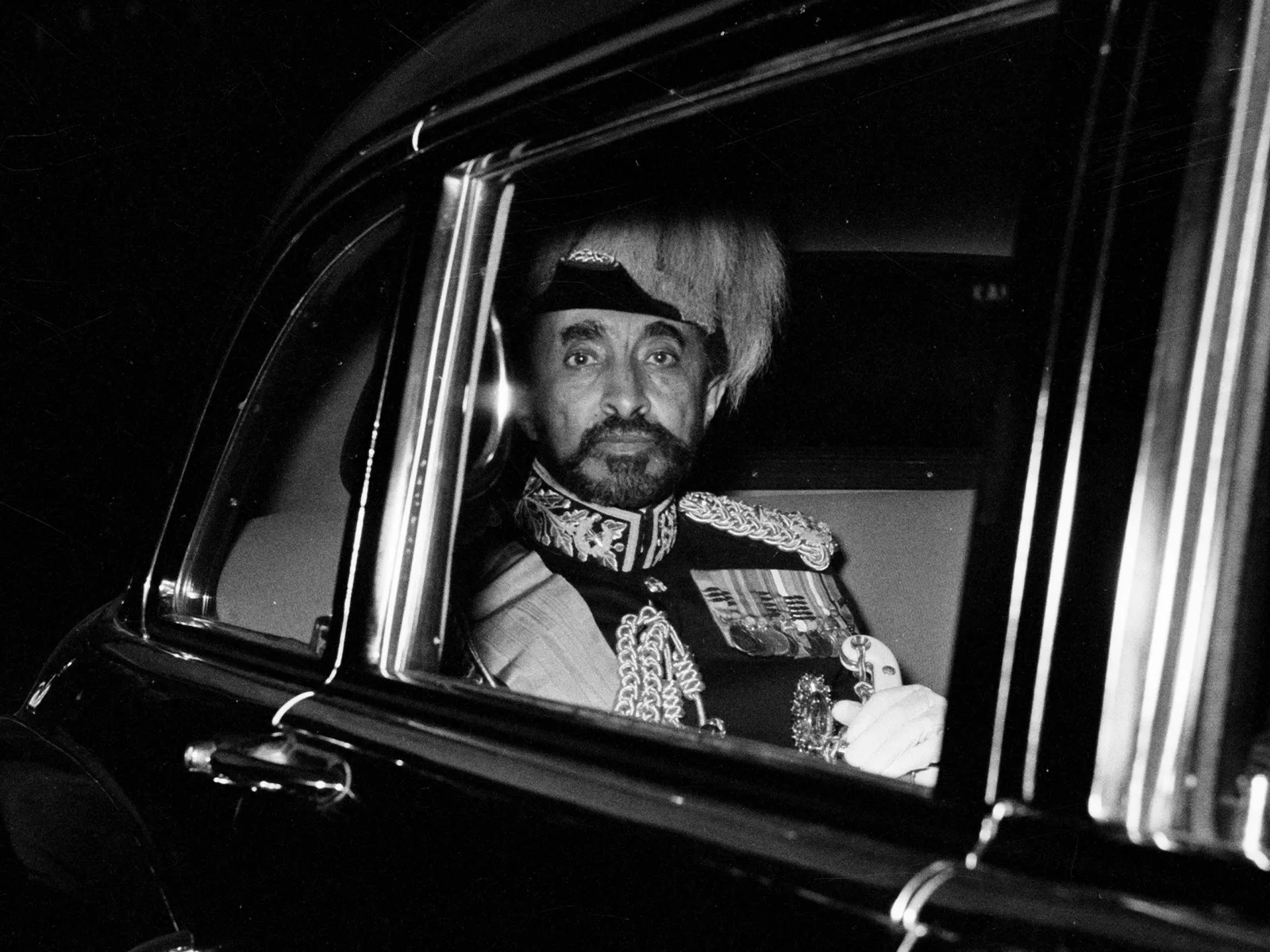

Engraving by Holzhalb: The Jews of Lengnau and Endingen pay homage to an allgorical figure. In the old Swiss Confederacy the Jews were required, every 16 years, to get a charter of protection and safe conduct (Schutz- und Schirmbrief) from the local bailiff (Landvogt). Lengnau synagogue can be seen in the background.

Swiss National Museum

But neither these restrictions, nor recurrent rioting by angry peasants (the Zwetschgenkrieg of 1802), could halt the growth of the two Jewish communities in the Surbtal Valley. Around 1780, 400 Jews lived in the village of Endingen, which had a total population of 1,000. The Jews increased in number to 1,000 by 1850, meaning that for several years they actually made up the majority of the population. They earned their living as livestock and horse traders, through merchant business and the production of straw products, as peddlers or Trödeljuden (‘junk Jews’) or, like Philippina Guggenheim, by keeping an inn that was run in line with ritual conventions.

As the community grew, so too did its efforts towards establishing the structures that would enable it to practice its religious and spiritual life. Lengnau’s first brick-built synagogue was inaugurated in 1750, with that of Endingen following in 1764. The Helvetian Almanac of 1786 reported, in an article with anti-Semitic undertones, on the Jews of the county of Baden: ‘The two synagogues bear the unmistakable stamp of the simplicity, the ineptitude and the character of their owners. […] The buildings are of inconsiderable size, but Endingen synagogue is not constructed without symmetry and taste.’

Hope for equality after the Helvetic Republic

After the collapse of the Helvetic Republic, the Act of Mediation issued by Napoleon Bonaparte established the Canton of Aargau in 1803. But for the Jews of the Surbtal Valley, the greater equality for which they had hoped failed to materialise. Quite the reverse, in fact! In 1809, the Aargau council enacted a law that placed the Jews under the police supervision of the canton government, and in 1824 an organisational law that put an end to the existing autonomy of the Jewish communities entered into force. This gave the canton the right to enact all kinds of rules, and it was even able to interfere in ritual matters. In the mid-1850s, the two communities applied for permission to build larger synagogues. The fact that, after much controversy, this request was approved by the Aargau great council (Grosse Rat) is attributed to the influence of liberal seminary director Augustin Keller, who wished, from a sense of paternalistic Christian belief, ‘to raise up the Israelites to the level of other social and civilised life, so that their culture will be different, proper and more similar to the character, the moral conventions, the conditions of our country.’

On 6 August 1847, the inauguration of the new Lengnau Synagogue took place – an event that was noted across Switzerland and also in neighbouring countries. The synagogue construction had been awarded to Zurich architect Ferdinand Stadler. Stadler, who in the course of his career would go on to create several more sacred buildings (the rebuilding of the Augustinerkirche in Zurich, the reformed church at Thalwil), designed a three-part architecture, characterised by a gabled roof and elongated arched windows.

In Endingen, where one third of the Jewish population of Switzerland lived in 1850, the official inauguration of the new synagogue was celebrated on 26 March 1852. The architect, Caspar Josef Jeuch (Aarau barracks), designed the façade with Moorish stylistic elements, thus creating the first synagogue building in Switzerland to make use of this style of ornamentation. Inside too, the paintings were kept in the ‘eastern style’. As a distinctive feature, a widely visible clock is mounted on the elegant frontage. This is probably in part because in Endingen it is not a church bell tower on the village square, but a synagogue that looms above the local farmers’ properties.

Meshaneh Makom, Meshaneh Mazal.

A change of place, a change of luck.

(Jewish saying from the Surbtal Valley)

From the mid-1860s, younger Jews started migrating out of the Surbtal Valley rural communities. Following the emancipation of 1867, they were now free to go anywhere in Switzerland. If the term ‘old-established Jews’ applies in Switzerland, it refers to those families, like that of former Federal Councillor Ruth Dreifuss, that can look back with pride on their Heimatrecht (right of residence) in Lengnau or Endingen.

Formal portrait of Augustin Keller.

Swiss National Museum

The Act of Mediation of 1803.

Swiss Federal Archives

Ruth Dreifuss after her election as a Federal Councillor in 1993.

Swiss National Museum / ASL