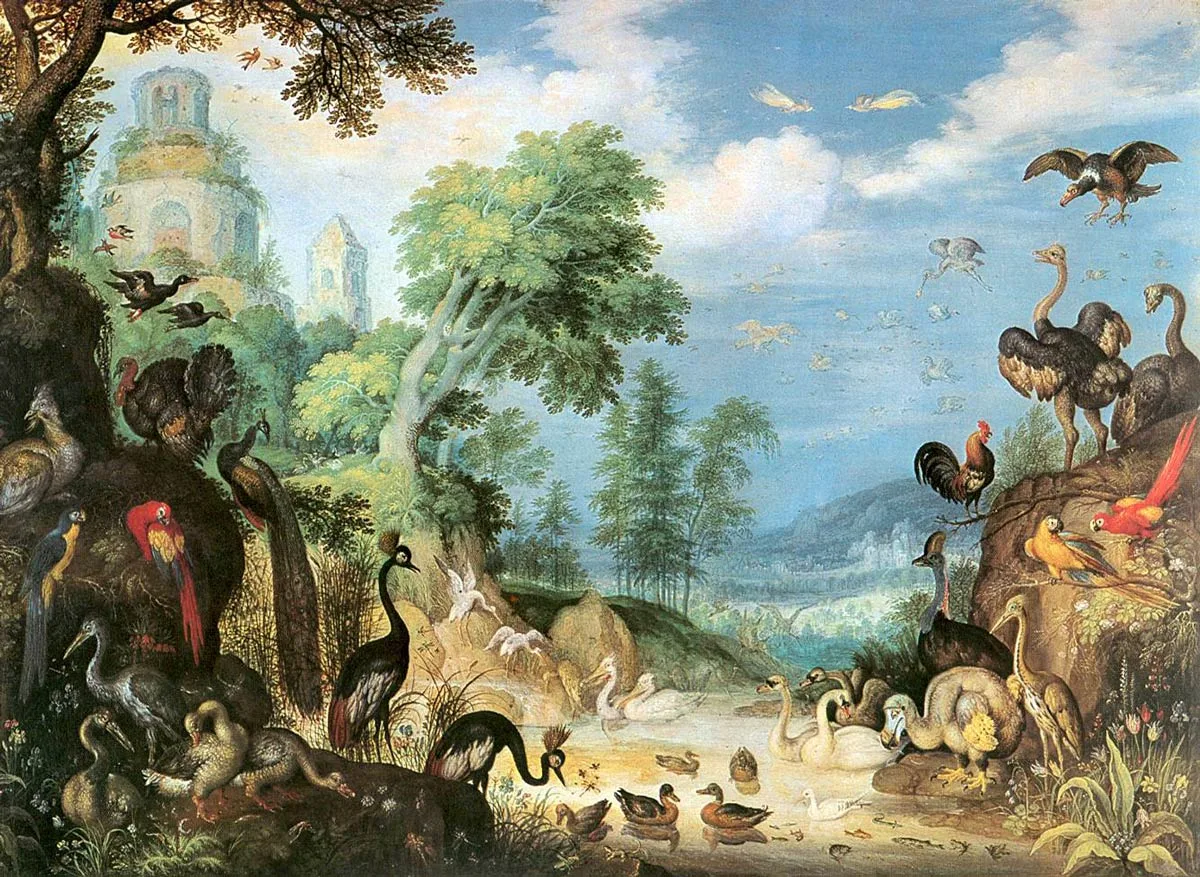

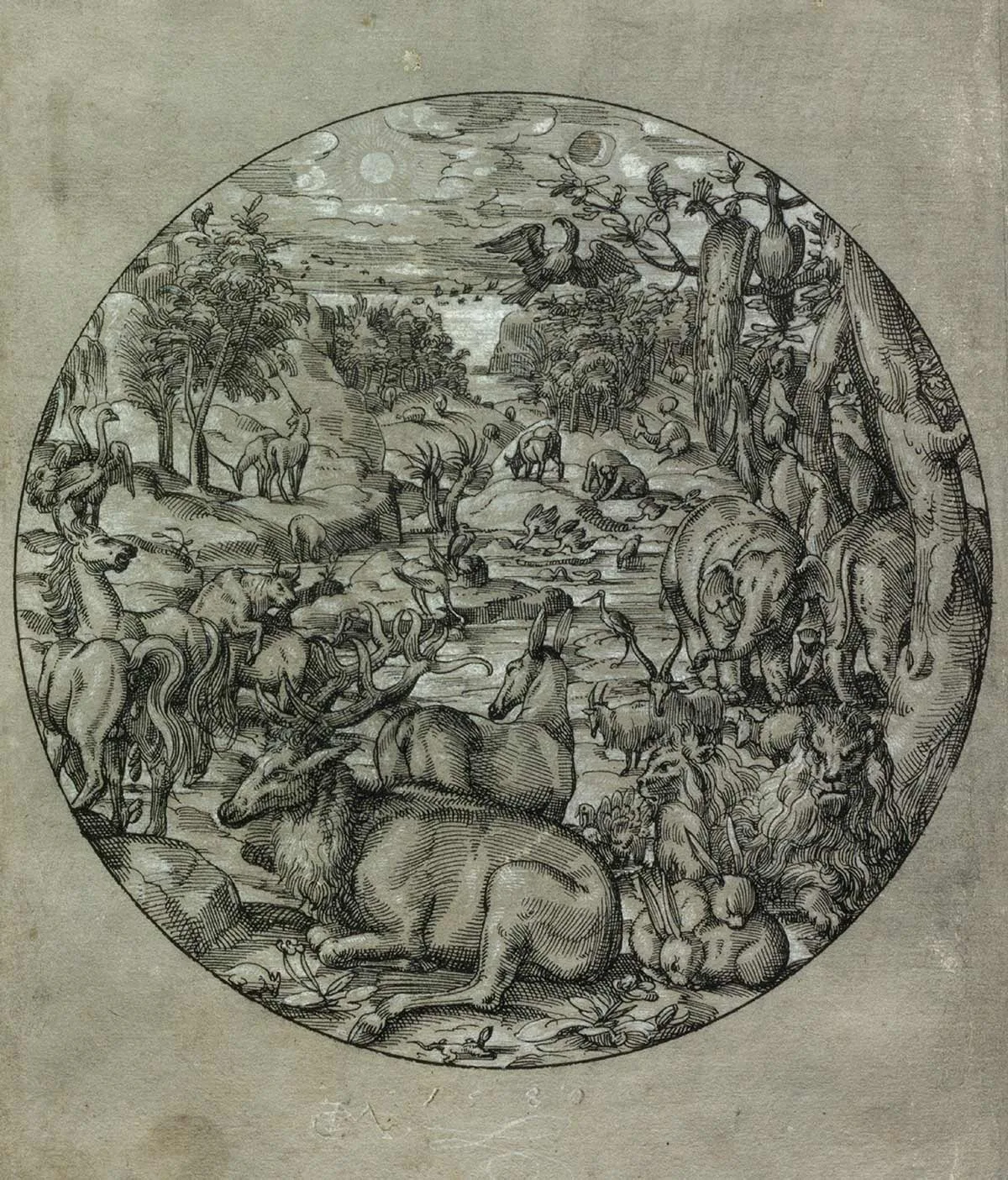

A teeming painting between art and science

Children love pictures teeming with animals, even in the 21st century. Roelant Savery was an expert in painting wildlife, and he used his skills to impress the Habsburg emperor over 400 years ago as well as inspiring many of his contemporaries, including Swiss artists.

At the emperor’s court

Savery and the animals

Peace in paradise — a pipe dream?