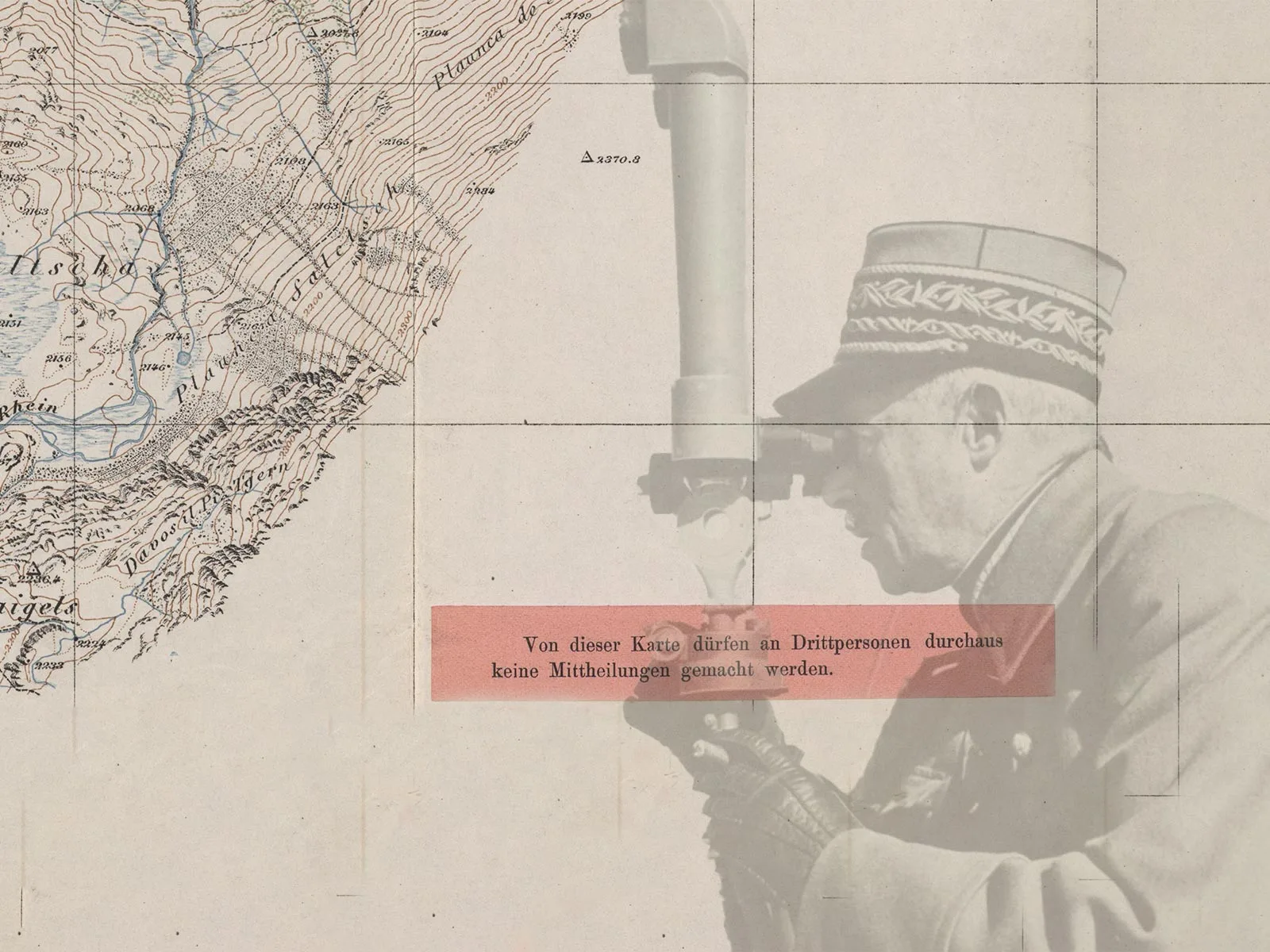

The secrets of Swiss maps

From secret maps to sales bans and retouching, various methods have been used in Swiss cartography to protect military secrets.

A secret and an official cartography

Just after the outbreak of the Second World War, in September 1939, Henri Guisan, General of the Swiss Armed Forces, noted “a certain interest in Swiss map series from some quarters that warranted close monitoring.” This observation was not without cause: in May 1939, the Swiss General Staff had already suspected the German Army of specifically ordering Swiss map series via a Berlin cover address. Guisan also criticised the fact that Swiss map stocks “were not sufficient to cover extraordinary replenishment needs, not even for the delivery of a second set of new maps to authorised staff and units.” Warfare was impossible without geospatial knowledge, so in the interests of defence preparedness, every available map was therefore to be seized and handed over to the armed forces.

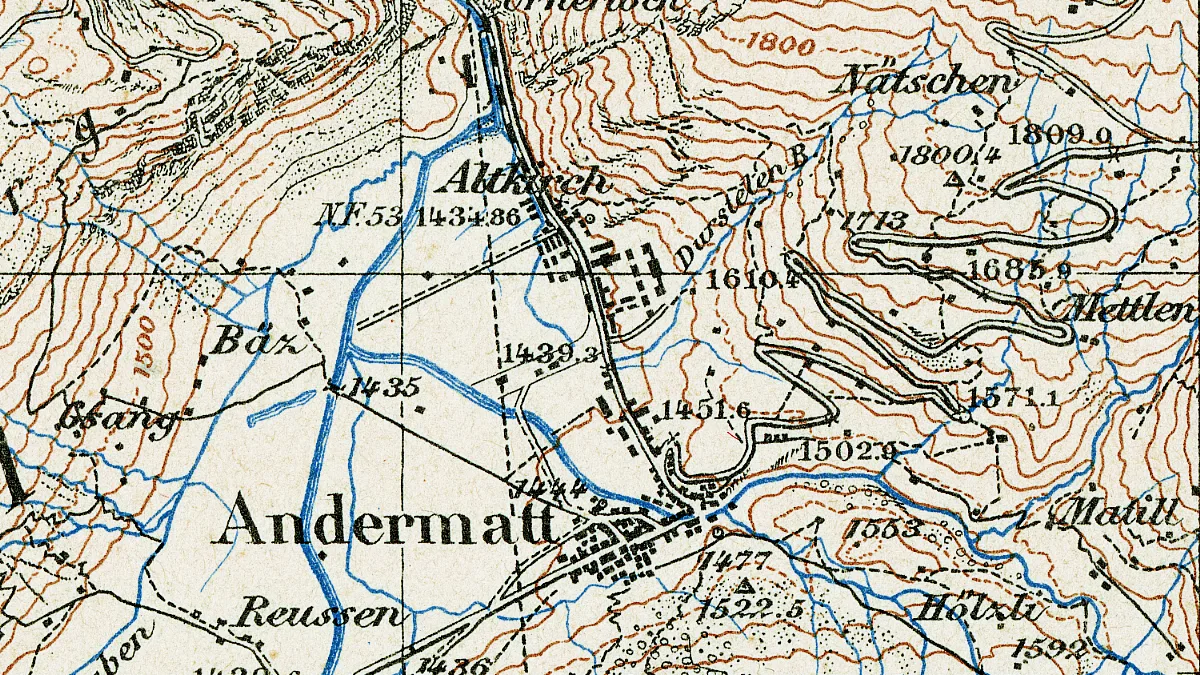

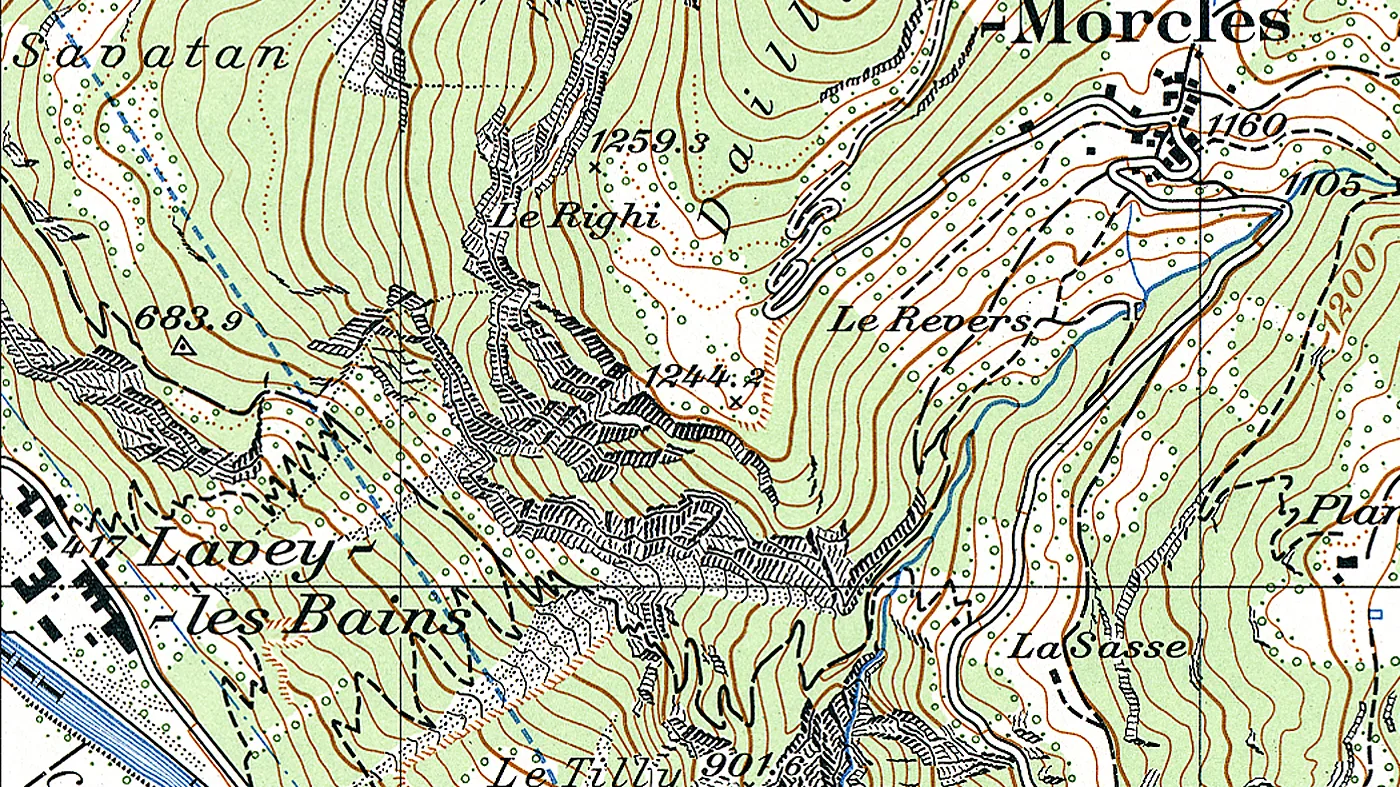

The Federal Council responded to the map shortage and the secrecy issue in October 1939 by completely banning the sale and export of maps of Switzerland at a scale of 1:1,000,000 or larger. The reproduction of information on Swiss terrain was also prohibited in books, newspapers and even on postcards. These measures were tantamount to widespread cartographic censorship and were only lifted after the war in the summer of 1945.

Secrecy through omission during the Cold War

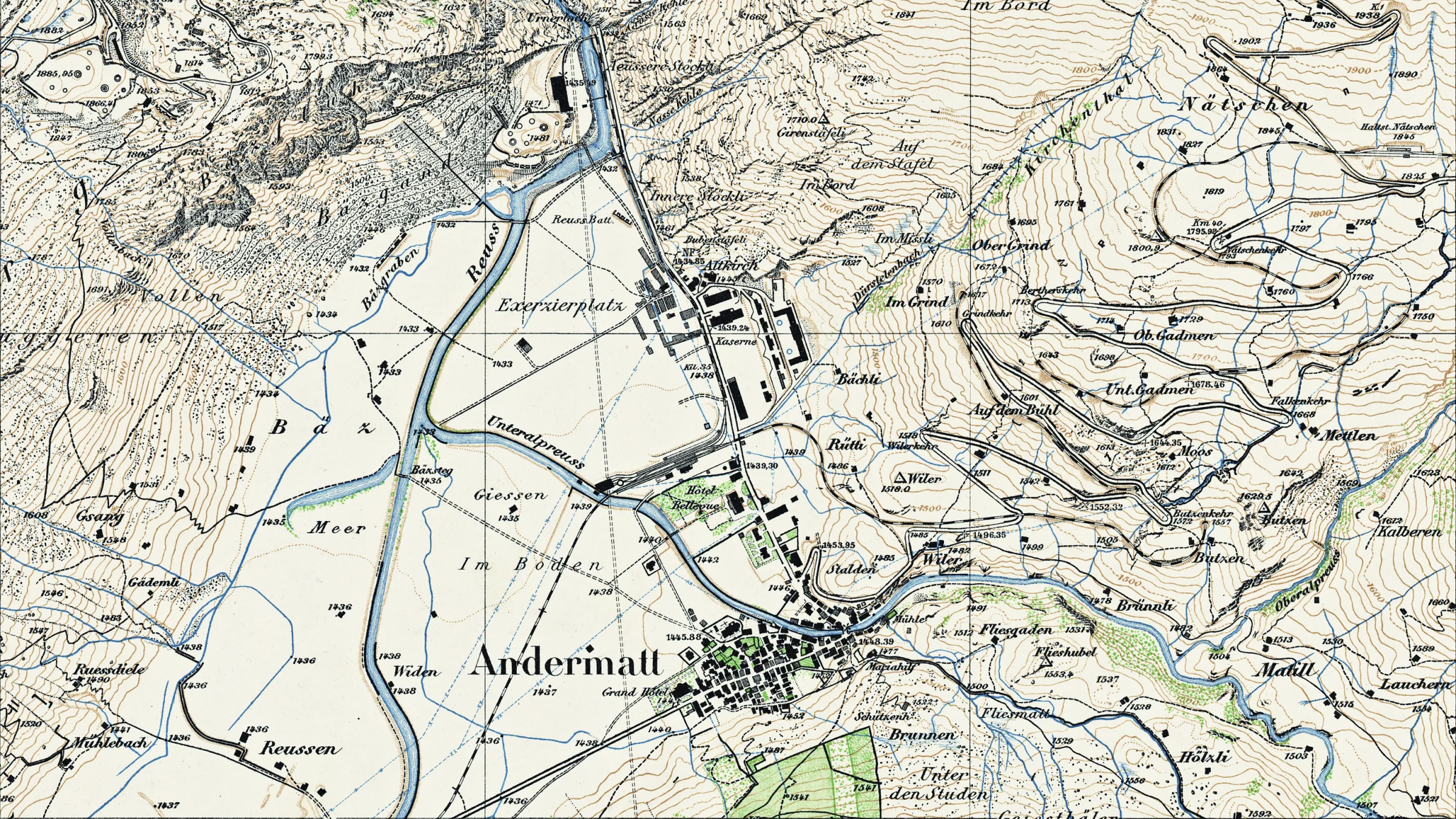

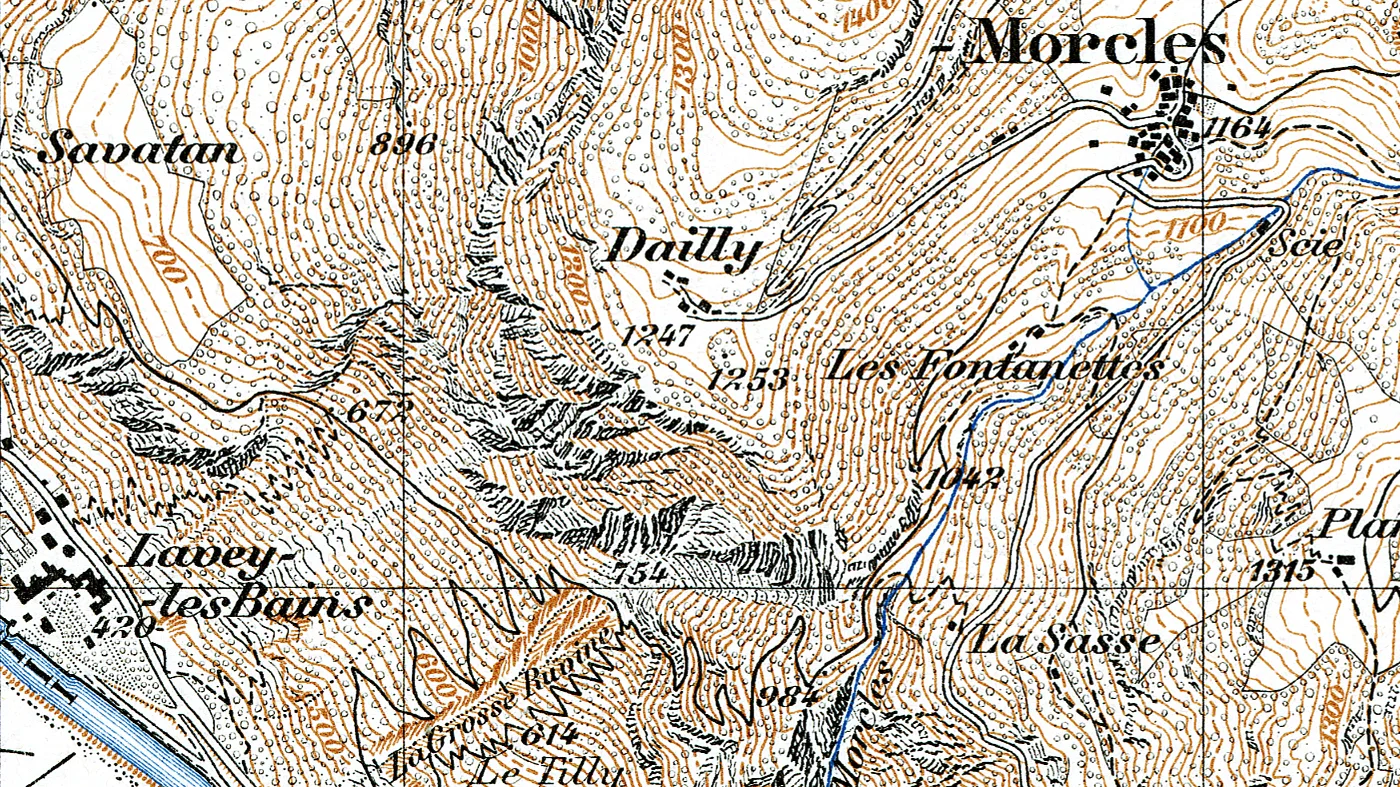

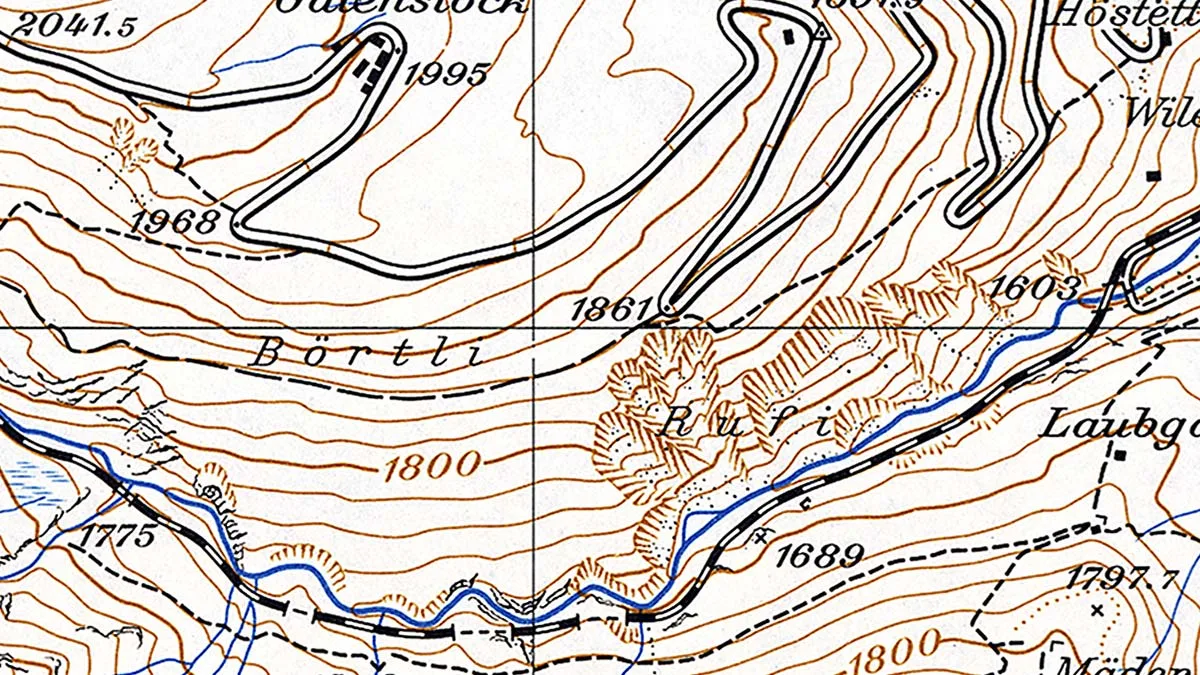

The cartographic secrecy strategy after 1945 focused more on specifically obfuscating important military installations on maps. Military airfields, tank traps, armaments factories and many other strategically-relevant objects disappeared from maps.

With or without a chalet?

During the Cold War doubts had already been raised about the effectiveness of cartographic concealment. Ultimately, it was technological progress that brought about a change in practice as remote sensing via satellite was so sophisticated by around 1990 that concealing objects on maps made less and less sense. Continuing to hide objects would even have had the opposite effect, drawing attention precisely to the features missing on the map. From 1991, new regulations and directives were drawn up that were geared towards the so-called ‘perceptibility principle’, according to which facilities that are perceptible on the Earth’s surface should also appear on maps. This principle has proved workable and still applies today.

Space and time

This article was originally published (in German and French) on the “Space and time” website of the Federal Office of Topography (swisstopo), where readers can regularly discover thrilling chapters from the history of Swiss cartography.